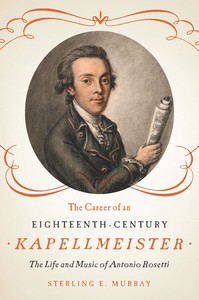

The Career of an Eighteenth-Century Kapellmeister: The Life and Music of Antonio Rosetti. By Sterling E. Murray. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2014. [xx, 463 p. ISBN 9781580464673. $99.] Music examples, illustrations, bibliography, index, companion web site.

{1} It is a fortunate coincidence that I am writing this review of Sterling E. Murray’s The Career of an  Eighteenth-Century Kapellmeister: The Life and Music of Antonio Rosetti during the same week of the latest union meeting for my local chapter of the American Federation of Musicians. In the main meeting room, I listened to my fellow professional musicians, voicing concerns over contract negotiations, questions of new markets, competitors overseas, and fears for an uncertain future of the possibility of retirement options. In the lobby, friends and colleagues caught up with each other, sharing stories of summer travels to music festivals, and their latest baby, puppy, or grumpy cat pictures with each other on their smartphones. The historian side of me couldn’t help but think about how things have both profoundly changed in 250 years, and also how many constants have stayed the same. While professional accomplishments such as being mentioned in major newspapers or commissions by very well-respected arts organizations are quite prestigious and look glamorous, often those lines on the résumé do very little on the day-to-day front for a composer’s basic needs like rent money, instrument upkeep, and supporting his/her family. Rewind 250 years and composers like Antonio Rosetti had successful premieres in venues such as Paris’s Concert Spirituel and Johann Salomon’s Hanover Square Rooms in London, only to be negotiating at home how much of a stipend could be allotted for wood for the fireplace stove and begging for loans to cover the cost of another child. The juxtaposition leaves the practitioner and historian of music to ask: What does a ‘successful’ life in music truly look like, both in public and in private? How is that definition of success rewritten for each artist?

Eighteenth-Century Kapellmeister: The Life and Music of Antonio Rosetti during the same week of the latest union meeting for my local chapter of the American Federation of Musicians. In the main meeting room, I listened to my fellow professional musicians, voicing concerns over contract negotiations, questions of new markets, competitors overseas, and fears for an uncertain future of the possibility of retirement options. In the lobby, friends and colleagues caught up with each other, sharing stories of summer travels to music festivals, and their latest baby, puppy, or grumpy cat pictures with each other on their smartphones. The historian side of me couldn’t help but think about how things have both profoundly changed in 250 years, and also how many constants have stayed the same. While professional accomplishments such as being mentioned in major newspapers or commissions by very well-respected arts organizations are quite prestigious and look glamorous, often those lines on the résumé do very little on the day-to-day front for a composer’s basic needs like rent money, instrument upkeep, and supporting his/her family. Rewind 250 years and composers like Antonio Rosetti had successful premieres in venues such as Paris’s Concert Spirituel and Johann Salomon’s Hanover Square Rooms in London, only to be negotiating at home how much of a stipend could be allotted for wood for the fireplace stove and begging for loans to cover the cost of another child. The juxtaposition leaves the practitioner and historian of music to ask: What does a ‘successful’ life in music truly look like, both in public and in private? How is that definition of success rewritten for each artist?

{2} In The Career of an Eighteenth-Century Kapellmeister, Sterling E. Murray seeks to answer those questions for one such success story. He has written the history and context of one of the most successful composers of the Classical and Galant styles who many outside of Eighteenth-Century Studies may never have heard of: Antonio Rosetti (ca. 1750–1792). He was a violone/bass player and composer born in Bohemia who spent the majority of his career in the employ of the Prince of Oettingen-Wallerstein in what is now Southern Germany. Rosetti achieved a good amount of renown during his own lifetime as a composer, with premiers of his works in Paris, London and Vienna, and was even asked to provide the requiem that was played at Mozart’s funeral in 1791. At the time of his death, over half of his more than 800 compositions had been published (385). He was also lucky enough to hold a relatively stable court position, where the Prince paid for a trip for Rosetti to travel to Paris and seek out publishing/performance opportunities for his symphonies. And yet, at the same time, throughout his tenure in Wallerstein, Rosetti was constantly in financial debt, begging the Prince for loans, and in return being asked to perform more duties as part of his job description without additional financial compensation. At long last, in 1789, Rosetti successfully applied for a very comfortable job at the nearby court of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, only to tragically die three years later, unable to fully take advantage of the benefits of such a relatively luxurious post.

{3} By his own admission in the introduction, Murray has spent 40 years researching the life and music of Antonio Rosetti, which is nearly as long as the composer himself was alive. He previously wrote sixteen articles on Rosetti’s life and the court culture at Oettingen-Wallerstein, edited five wind partitas for A-R Editions, and contributed the entry on Rosetti to the New Grove. Most significantly, Murray previously published The Music of Antonio Rosetti (Anton Rösler), ca. 1750–1792: A Thematic Catalog (Warren, Michigan: Harmonie Park, 1996), creating one database listing of Rosetti’s entire oeuvre and giving a Murray catalogue number to each composition. So, it is fitting that the culmination of all this research is the first biography on this composer’s life and work.

{4} Murray’s stated goal in writing this monograph is to make a case for more favorably considering so-called Kleinmeister (small/lesser masters) of the Classical Era—particularly those from Bohemia—alongside the likes of Mozart and Haydn. In doing so, the inclusion of minute details that the author provides about daily musical and domestic life in lower-level courts like Wallerstein—such as business transactions, bread and wine allotments, and instrument doubling—goes beyond the scope of Rosetti and humanizes the careers of those contemporary composers, like Haydn, for example, whose names are more familiar to us than Rosetti’s, but whose lives seem more remote and romanticized.

{5} The book is divided into two parts, the first comprising the biography of Rosetti’s life, and the second a detailed survey of Rosetti’s entire compositional output. Additionally, a supplementary website is provided for additional texts, translations, and engraved musical examples. Both parts are written in a very accessible style.

{6} Part One, “Biography and Context,” will be useful to anyone doing work on eighteenth-century musical life in the Germany/Bohemia region, no matter what composer is the focus of study. The details that Murray discusses here may hold interest to anyone who has pursued a career in music, or is currently in the field of historical performance. Murray draws on a voluminous and varied amount of archival data: birth records, pay records, personal letters, comparable data from neighboring courts, surviving artworks, and even existing examples of livery, to put together a realistic and practical idea of what it was like to live and work at the Oettingen-Wallerstein court, and to a lesser degree the Mecklenburg-Schwerin court. Murray presents intricate details from the important figures, such as patron Prince Kraft Ernst himself to the oldest member of the orchestra, Albrecht Sebastian Link: violinist, curator of musical instruments, music librarian, and occasional copyist. Other surprising doubling members of Rosetti’s orchestra were Ignaz Höffler, the violinist and pastry chef, and Johannes Türrschmidt, the principal violist who often played horn. In addition, Murray provides sections delving into the basic domestic concerns of the musicians, from salaries and pay scales, debt problems, housing, and clothing, to the practical nature of being a performer. The details the author provides include figures of how many reams of paper the court went through in a year, and who was in charge of purchasing new bows for strings and fixing joints of the court oboes. As a 21st-century musician who went to a university where the school Stradivarius was ‘lost’ for almost thirty years, 1 I couldn’t help but be amused by the mention of musicians who walked off with some of the Wallerstein library manuscripts, or most egregiously, the Hopfkapelle member Joseph Fiala, who evidently walked off with an oboe, two English horns and a violin.

{7} While Rosetti necessarily remains the central figure throughout Part One, what emerges over the narrative is a historical portrait of a musical community nestled in rural Germany, and a group of musicians who lived, worked, and died together. The inclusion of the exact roster of musicians, including their instrument(s), how long they were employed at the court, and how skilled they were, means that as the reader moves onto the musical discussion section of the book, it is easy to imagine the orchestra that Rosetti was writing for in his compositions.

{8} In Part Two, “The Music,” Murray presents a survey of Rosetti’s entire catalog, highlighting particular pieces of interest. The chapters are broken up by genre, such as: Symphonies, Concertos, Chamber Music, Domestic Music: Keyboard Pieces and Lieder, Music for the Church, and Harmoniemusik (wind band music). Murray highlights Rosetti’s ingenuity, in particular, in writing for winds and brass in his concertos and symphonies, directly linked to the quality of his colleagues he was writing for at Wallerstein. Where Mozart codified the piano concerto in writing twenty-seven examples, Rosetti may be on the road of comparable distinction for the horn, as he composed sixteen concertos for solo horn and an additional six for two horns. This is just one example of Rosetti’s situation at Wallerstein of knowing his fellow musician’s capabilities extremely well. While Murray is quite concerned with proving that Rosetti was a competent composer in terms of formal and harmonic procedures, it would be wonderful for a future scholar to situate kleinmeister composers, including Rosetti, within the Galant musical analyses such as those in Robert Gjerdingen’s Music in the Galant Style (Oxford, 2007). Gjerdingen’s work in comparing many lesser-known composers alongside their more famous counterparts could be a nice way to contextualize Rosetti’s style with that of his contemporaries.

{9} In all of this musical discussion and analysis however, the difficulty in Part Two lies in trying to describe the grace, delicate texture, subtlety of orchestral color, and ingenuity of Rosetti’s musical style from text and score snippets alone. The author seeks to describe the music as much as possible in prose, and the additional extra resources and score examples on the website do help. However, this monograph would be a project that would greatly benefit from the inclusion of accompanying recordings, such as those in Nina Treadwell’s Music and Wonder in the Medici Court (University of California, 2008). A survey of music retailers and YouTube reveals that members of the early music community are taking up the torch in recording this music to promote Rosetti’s works beyond that of the printed page, of the score, or academic tome. Modern editions are slowly becoming available, and many of the Rosetti manuscripts are also available on www.imslp.org, but much of his catalogue remains unknown to scholars as well as the general public.

{10} At the end of The Career of an Eighteenth-Century Kapellmeister, I was left with a few questions about the more intriguing details of Rosetti’s life, such as the discrepancy between the Germanicized/Italianicized versions of his name (Anton Rösler vs. Antonio Rosetti). I wondered, too, how his music may or may not have fit in with perceptions of Italian music in Germany and Bohemia. More striking, however, are the questions posed by Murray’s closing chapter, which asks the very real question of how does someone like Rosetti, and this kind of life and legacy, get forgotten? How did the history of the Classical Era get simplified down, as Neal Zaslaw laments, as “the least well represented in the area of scholarly publication” and boiled down to being “simply the age of Haydn, Mozart, and perhaps Gluck”? 2 Again, the question is an open door for a new generation of scholars to continue Murray’s work on composers such as Antonio Rosetti, to along the way discover that while we don’t have to deal with periwigs in 2014, many of the issues that contemporary musicians and composers struggle with today have been negotiated and renegotiated in order to define ‘success’ for quite some time. I’m sure more than a few of today’s musicians wouldn’t mind citing this text to argue for bringing back wine and beer as part of their benefits package (99), but I think the violists would definitely take issue with doubling on horn again.

***

Lindsey Strand-Polyak holds a Ph.D./M.M. in Musicology and Violin Performance from the University of California, Los Angeles, is the Guest Director of the UCLA Early Music Ensemble, and is active as a baroque violinist and violist throughout the United States. http://www.strandpolyak.com

***

Notes

- Associated Press, “A Stradivarius Lost 27 Years Now Brings Tug-of-War,” New York Times, October 23, 1994, http://www.nytimes.com/1994/10/23/us/a-stradivarius-lost-27-years-now-brings-tug-of-war.html (accessed July 31, 2014). ↩

- Neal Zaslaw, Introduction to A-R Editions’ “Recent Researches in the Music of the Classical Era,” https://www.areditions.com/rr/rrc.html (accessed July 31, 2014). ↩