The media coverage of rapper Eminem in the days immediately preceding and following the 2001 Grammy awards rehearsed a number of common tropes regarding controversial art forms: is free artistic expression more important than a moral social order? Is there a distinction between individual expression and commercial manipulation? Do portrayals of violence beget more violence? Is rap music indeed “music”? Concerns about vulgar language, homophobia, and the degradation of women arose from a range of voices because The Marshall Mathers LP had been nominated for the prestigious “Album of the Year” award by the members of the National Association of Recording Arts and Sciences. According to C. Michael Greene, then the Grammy organization’s president, the nomination was intended to “recognize [Eminem’s] music and not his message” (All Things Considered). At the time, I found feminist objections to Eminem’s depictions of violence against women particularly salient perhaps because, between the Music History Sequence and the Opera History course I was then teaching, I tallied a depressingly large number of dead women. My gruesome accounting revealed four women murdered by jealous husbands or boyfriends; two killed or raped by authority figures; one ritually sacrificed; and five who died after having been seduced and abandoned or forced to marry against their will—for a body count of twelve dead women in one semester of teaching. And that did not include tuberculosis victims.1

Catherine Clément’s Opera: or, The Undoing of Women has come into and then gone out of fashion, but our canon remains littered with women’s corpses.2 When I attempt to problematize these works for my students, the bodies will not stay buried. For example, when I discuss the social dimensions of Wozzeck, the anti-hero’s oppression at the hands of the Doctor and the Captain, and how he reproduces that oppression by murdering Marie, it is not uncommon for students to remark, “I thought he killed her because she cheated on him,” as though that were a reasonable explanation and even a natural consequence of female infidelity.

Thus, it struck me then, as I will argue here, that the misogynistic violence of Eminem’s rap songs has at least as much to do with the traditions of “whiter” aesthetic forms—opera, cinema, bluegrass murder ballads3—as it does with the conventions of gangsta rap: the very appeal of these rap songs depends on a widespread acceptance of violence against women as a cultural norm. In making this claim I wish both to acknowledge and to amplify Tricia Rose’s observation that “some rappers’ apparent need to craft elaborate and creative stories about the abuse and domination of … women … reflect[s] the deep-seated sexism that pervades the structure of American culture” (15).4 I also wish to suggest that, due to Eminem’s status as a white rapper masquerading within a black genre but supported by a predominantly white recording industry, his murder rap songs simultaneously serve the fantasies of white men and deflect blame for their regressive gender politics onto the putative violence and lawlessness of the black urban culture that engendered hip-hop. bell hooks’ comments on Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice are relevant here: she both condemns the book’s advocacy and celebration of rape and cautions that “we need to remember that it was a white-dominated publishing industry which printed and sold Soul on Ice. While white male patriarchs were pretending to respond to the demands of the feminist movement, they were allowing and even encouraging black males to give voice to violent woman-hating sentiments” (136).

sexism that pervades the structure of American culture” (15).4 I also wish to suggest that, due to Eminem’s status as a white rapper masquerading within a black genre but supported by a predominantly white recording industry, his murder rap songs simultaneously serve the fantasies of white men and deflect blame for their regressive gender politics onto the putative violence and lawlessness of the black urban culture that engendered hip-hop. bell hooks’ comments on Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice are relevant here: she both condemns the book’s advocacy and celebration of rape and cautions that “we need to remember that it was a white-dominated publishing industry which printed and sold Soul on Ice. While white male patriarchs were pretending to respond to the demands of the feminist movement, they were allowing and even encouraging black males to give voice to violent woman-hating sentiments” (136).

Robin D. G. Kelley has argued that, for many white, middle-class, male teenagers, gangsta rap provides an “imaginary alternative to suburban boredom”: “[T]he ghetto is a place of adventure, unbridled violence, and erotic fantasy,” which these young men consume vicariously and voyeuristically (122). This, claims Kelley, explained the “huge white following” of NWA (Niggaz with Attitude). Unlike some previous white rappers, Eminem’s credentials of “ghetto authenticity” have been established through his urban Detroit upbringing, his black homies, and rise to fame through MC battles—actual head-to-head rapping contests.5 Rap and urban music periodicals (The Source, Vibe, Rap Pages) have consistently held Eminem’s verbal ability in high regard, calling him “a white boy who can hang with the best black talent based on sheer skill” (Coker 162).6 Moreover, it was Dr. Dre of NWA notoriety who provided Eminem’s first recording opportunity, essentially launching his career. Dr. Dre remains Eminem’s chief producer.

Eminem can and does deliver the lurid goods for the delectation of suburban white boys, and he does it in whiteface, virtually guaranteeing greater access to the money and machinery of the music industry. Reflecting on the commercial advantages of white rappers, Eric Perkins recalled an alleged statement of Sun Records’ Sam Phillips from the early 1950s: “’If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars.’ That white man [was] Elvis Presley” (Perkins 36).7

In addition to noting that rap is only the latest genre of black American music to be appropriated by white culture, some critics have drawn parallels between white rappers (“the great white hoax” qtd. in Perkins 35) and blackface minstrelsy: when Al Jolson donned blackface, one critic observed, he became the first Beastie Boy (White 198). Such masquerades may be motivated less by purely musical interests than by a desire to hide behind the guise of another in order to transgress social norms. Dale Cockrell has argued, for example, that some early blackface minstrels protested social conditions while in their “Ethiopian” disguises.8 But other instances suggest that the musical discourse of the “Other” facilitates and justifies fantasies of illicit pleasure, a kind of carnivalesque colonialism: fictive orientalisms, the tango, and jazz have variously served to represent sexual license for the delectation of European or American audiences. Thus, the ghetto is only the most recent port of call for European/American musical tourism.

If the structure of Eminem’s CDs—with their mix of jokes, skits, danceable tunes, satire, self-abasement, and racial and gender impersonation—bears a certain resemblance to a minstrel show, a more significant parallel is minstrelsy’s “mixed erotic economy of celebration and exploitation”: like Eminem’s fans, the blackface minstrels’ audiences were predominantly white and male, and their fascination with and anxiety about minstrelsy, nineteenth–century America’s most popular form of entertainment, were bound up with received notions of black masculinity. For the young white men and boys whose fanship made Eminem’s most recent CD “go platinum” before its release (Richtel C4), the rapper’s sonic “blacking up” is, to use the words of Eric Lott, “less a sign of absolute white power and control than of panic, anxiety, terror, and pleasure” (6).9  Many of Eminem’s first-person tales of drugs, violence, and domination of adversaries represent the urban exotic for the thrill of white boys in their emulation of the language and attitudes of the “real Nigga,” the gangster and the pimp, thus invoking constructions of black masculinity with roots in pernicious stereotypes.10 In the same sleight of race operative in blackface minstrelsy, Eminem, by virtue of his popularity and media attention, has become the most widely recognized emblem of gangsta rap, his homophobia, misogyny, and violence reinforcing stereotypes not about white men, but rather, about black men.11

Many of Eminem’s first-person tales of drugs, violence, and domination of adversaries represent the urban exotic for the thrill of white boys in their emulation of the language and attitudes of the “real Nigga,” the gangster and the pimp, thus invoking constructions of black masculinity with roots in pernicious stereotypes.10 In the same sleight of race operative in blackface minstrelsy, Eminem, by virtue of his popularity and media attention, has become the most widely recognized emblem of gangsta rap, his homophobia, misogyny, and violence reinforcing stereotypes not about white men, but rather, about black men.11

A screenshot of Eminem’s official website.

Hip-Hop Meets Family Melodrama

The two murder raps under discussion here, however, are not set against an exoticized urban landscape of pimps and hoes and do not speak in the tongue of sexual braggadocio; rather, they resemble any other bourgeois melodrama in their presumption of the rightness of the patriarchal, nuclear family. Their suggestion that this caring father has become a murderer only because his immoral wife has pushed him beyond his limits resonates with the moral claims of conservative, father-oriented movements, such as The Promise Keepers.12 In this context, the “whiteness” of the violence is clear: according to U.S. Department of Justice statistics, the numbers of black women murdered annually by intimate partners have dropped by half since 1976, but those of white women have been “especially stubborn, varying from 800 to 1000” per year during the same period (see American Bar Association).13

Like bluegrass murder ballads, “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” from The Slim Shady LP and “Kim” from The Marshall Mathers LP concern a murder prompted by sexual jealousy in a monogamous, heterosexual relationship, and they relate the events from the murderer’s point of view. While their small scale and focus on the murder event align them with ballads (as opposed to an opera or a movie, in which the murder is only one of many events, and more than one point of view is apparent), the fact that the songs unfold at the same time as the action, rather than narrating events of the past, more closely resembles those larger-scale dramatic forms.

In both songs, the victim is the protagonist’s estranged wife, and the precipitating event is her remarriage to another man, construed by the protagonist as infidelity and setting up the transgression-and-punishment paradigm that informs so much nineteenth–century opera and literature.14 The “realist” aesthetic of the songs suggests an alignment with film noir, as does their implication that it is the woman’s act of independence that wreaks disaster: “[Putting] self-interest over devotion to a man,” according to film historian Janey Place, “is often the original sin of the film noir woman” (Kaplan 2–3; Place 47). While the murderer’s revenge for this failure of wifely devotion comprises the written narrative of both raps, the unwritten narrative—the act that the protagonist avenges—is the wife’s initiative to remove herself and her daughter from an abusive relationship.15

In both “Kim” and “’97 Bonnie and Clyde,” the feckless wife is contrasted to the innocent baby daughter, a pre-sexual and therefore pre-dangerous female, on whom the murderer lavishes affection in chilling juxtaposition to the slaying. In addition to their narrative similarities, the two songs have similar structures: both use sound effects to portray location and action (car doors slamming, dragging the wife’s body through the bushes, passing traffic); both use rapped lyrics for the verses, where the narrative is told; and both have a sung refrain that ironically reworks romantic tropes.16

The song title “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” refers to the father and daughter, now outlaws, who remain after the wife has been murdered, and the song’s refrain, “just the two of us,” which takes its lyric from Grover Washington Jr.’s 1980 romantic ballad, is transposed to the father/daughter dyad.17 Reference to the glamorous criminal couple Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker is not unique in the genre of gangsta rap: Yo-Yo and Ice Cube cut two tracks under that name (“The Bonnie and Clyde Theme” from You Better Ask Somebody and “Bonnie and Clyde II” from Total Control), followed by Jay-Z and Foxy Brown’s “Bonnie and Clyde Part II” (Chyna Doll), which Jay-Z also recorded with Beyonce Knowles of Destiny’s Child, among others. Notably, these other rap songs on the Bonnie and Clyde trope are duets with two adults interacting as equal partners, a distinct difference from “’97 Bonnie and Clyde,” where “Clyde’s” peer has been extinguished and replaced by a clearly subordinate child. Of course, all of the Bonnie and Clyde raps invoke Arthur Penn’s popular 1967 movie of the same name, “the most explicitly violent film that had yet been made” (Prince 9), and generally credited with ushering in the American cinematic norm of “ultraviolence.”18

As “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” opens, the murder has already taken place, and father and daughter go to dump the wife’s body. The circumstances of the murder are revealed gradually through the father’s reassuring prattle to the child, expressed partly as baby talk, partly as that rationalization parents use to keep children from fretting, such as, “don’t worry about that boo-boo on mama’s neck; it don’t hurt,” after the murderer has slashed her throat.19 I find this song both horrifying and compelling. Eminem’s jesting tone and smooth rapping style, the danceable rhythmic groove, the dark humor of the lyric and clever narrative twists engage me even as I recoil from what the words signify: “Say good-bye to Mommy … no more fighting with Dad … no more restraining order … We’re gonna build a sand castle and junk, but first help Dad take two more things out [of] the trunk” (Example 1).

The wife silenced, only the murderer’s point of view is presented: “Mommy was being mean to Dad and made him real, real mad. But I still feel sorry I put her on time out.” But the suppressed narrative—the woman’s perspective—can be gleaned from brief verbal cues (like “restraining order”) and from this tale’s similarity to a real-life scenario that occurs with depressing frequency: stalked by her former spouse, the wife had been granted a restraining order against him to no avail, for the stalker murdered her, her new husband, and her step-son (Example 2).20 Even further in the narrative background is a history of violent and controlling behavior during the marriage: according to the National Violence Against Women Survey, stalkers do not typically begin these behaviors after the relationship has ended; rather, the stalking behavior is merely an extension of the relationship, one that the victim generally leaves only after having suffering protracted abuse.21 Acquaintance with the alarming frequency of spousal abuse, stalking, and spousal murder creates a strong cognitive dissonance between the song’s humorous affect and the gravity of its implications.22

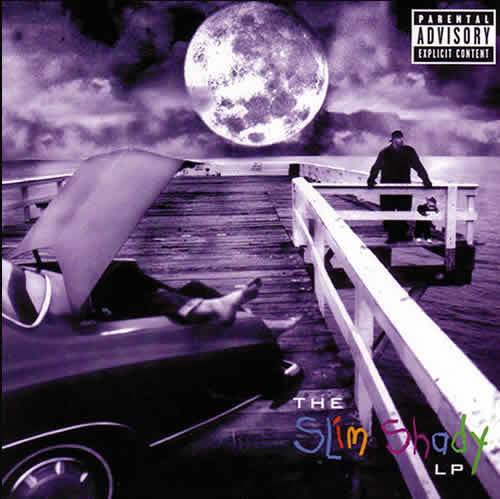

The scenario of this song is depicted on the cover of The Slim Shady LP (Figure 1).23 In the foreground, a woman’s legs and bare feet protrude from the trunk of a car, and in the middle ground, father and daughter stand together at a pier from which the woman’s body will be dumped. Since this LP is named for Eminem’s gangster persona, Slim Shady, we might assume that Slim is the protagonist of this song.24

Fig. 1. The crime in progress: cover of Eminem, The Slim Shady LP (©Aftermath Entertainment/Interscope Records, 1999 INTD-90287) Photo by Danielle Hastings or Christopher McCann

“Kim” reprises the same murder under the same circumstances as “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” in a more graphic and viscerally repulsive way. The Marshall Mathers LP carries the realist aesthetic further by using Eminem’s real name and that of his former wife, Kim, in the LP title and the song title, respectively, and the real name of their daughter, Hailie, in the song text. The words of the sung refrain, “I don’t want to go on living in this world without you,” could be an expression of romantic longing … except that they are preceded by the words, “So long, bitch, you did me so wrong.” After several tender moments in which Mathers puts his daughter to bed, the song makes a sonic jump-cut to a scene of rage, verbal abuse and murder (Example 3). With none of the clever conceits of “’97 Bonnie and Clyde,” this murder happens before the ears of the listener, the sonic equivalent of a slasher film: sensational, yet banal.25 Mathers ventriloquizes the part of Kim as a terrified, pleading victim, unable to act in her own defense and willing to reconcile with her former spouse in order to save her own life, even after he has murdered her new husband and stepson. By putting words into Kim’s mouth, Mathers exerts complete control over the fantasized interaction—a distinct difference from the “dialogic contestation” Rose and others have identified in some rap music.26 The murder culminates in the repeated, shouted command, “Bleed, bitch, bleed!” and Kim’s gurgling protests as Mathers cuts her throat. As with “’97 Bonnie and Clyde,” the final sounds represent the disposal of the body and the murderer’s departure (Example 4).

Fig. 2. “Poor White Trash”: inside photo, Eminem, The Marshall Mathers LP (Aftermath Entertainment/Interscope Records, 2000) 069490629-2 Photo by Jonathan “Xtra Gangsta” Mannion.

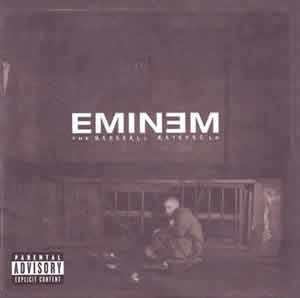

If The Slim Shady LP portrayed Eminem as a gangster—a common enough representation in rap music—The Marshall Mathers LP portrays him as “poor white trash,” a member of the downtrodden, signaled visually by photos on the back and inside front covers of the liner notes (Figure 2) and on the CD. In these photos Mathers appears in a T-shirt and apron of a food service worker, and he is depicted, literally, picking up the trash. The photo on the actual CD (not depicted here) was shot from above, giving visual emphasis to his low social status.

Fig. 3. Homeless: cover of Eminem, The Marshall Mathers LP (Aftermath Entertainment/Interscope Records, 2000) 069490629-2.

The cover photos of the CD, although less literal in terms of “trash,” depict Mathers as a poor person: in one version of the cover, he sits on the porch of a weather-worn house, and in the other, he appears to be homeless (Figure 3). The white trash imagery of the CD and realist aesthetic of “Kim” serve to authenticate the song as a “genuine” expression of rage from a member of an oppressed underclass, and the CD’s visual portrayals and often self-pitying texts ask us to sympathize with the murderer rather than with his victims.27 While its real-time, tell-all quality tends to place “Kim” in a camp with the voyeurism of “reality” TV, its ostensibly Lumpenproletariat sympathies suggest some hyperreal version of Berg’s Wozzeck.

Reality Check

In one sense, the realities of the rapper’s off-stage violence and vexed relationships with women have little bearing on the degree to which these songs participate in a broader economy of violence: the argument of the songs is already familiar to us (“bad” women must be killed), and listeners who share this sentiment relate to the songs, whether or not Eminem claims the sentiment himself. But the details of Eminem’s relationships are frequently cited in ways that seem to justify or explain the vehemence of his woman-hating lyrics. While Mathers and his wife were estranged but still married, he did stalk her and pistol whip a man he believed he saw kissing her, leading to a felony weapons charge for the rapper.28 The similarity of this event to the murder raps bolsters their reality aesthetic, yet the fact that the incident stopped short of murder allows the rapper to claim that the lyrics are not real, that he doesn’t really mean them.

women must be killed), and listeners who share this sentiment relate to the songs, whether or not Eminem claims the sentiment himself. But the details of Eminem’s relationships are frequently cited in ways that seem to justify or explain the vehemence of his woman-hating lyrics. While Mathers and his wife were estranged but still married, he did stalk her and pistol whip a man he believed he saw kissing her, leading to a felony weapons charge for the rapper.28 The similarity of this event to the murder raps bolsters their reality aesthetic, yet the fact that the incident stopped short of murder allows the rapper to claim that the lyrics are not real, that he doesn’t really mean them.

Eminem and his handlers want to have it both ways: on the one hand, we are supposed to understand his lyrics as emanating from his deep-seated emotions and dismal life experiences, and are therefore justified. But on the other hand, we are supposed to read his performances as parody, theater, or deliberate provocations to his critics and not take them seriously: the kids “get the joke,” so why can’t we? (DeCurtis, “Eminem Responds” 18). Either way, authentic or parody, real or unreal, the violent content is rationalized.

Describing the origins of his murder ballads, Eminem explains that he and Kim,

… weren’t getting along at the time. None of it was to be taken literally … Although at the time, I wanted to fucking do it. My thoughts are so fucking evil when I’m writing shit, if I’m mad at my girl, I’m gonna sit down and write the most misogynistic fucking rhyme in the world. It’s not how I feel in general, it’s how I feel at that moment. Like, say today, earlier, I might think something like, “Coming through the airport sluggish, walking on crutches, hit a pregnant bitch in the stomach with luggage.” (Bozza, “Eminem Blows Up” 72)

Not only does this account slither around the real/unreal discourse, it suggests that misogyny is a creative response warranted by certain circumstances in an intimate relationship. This type of explanation is accepted at face value by many journalists, but it misrepresents the nature of misogyny: it is not an accessory, like a hat that you can put on or take off depending on your mood; rather, it is a worldview that informs choices and interpretations.

Eminem’s world view, as it emerges in interviews, is largely consistent with the one represented in his murder ballads. He regards his behavior in the stalking incident as normal, manly, perhaps even heroic:

I didn’t do anything different than any other person would have done that night [when he caught Kim kissing another man]. Some people would have done more than me, but I don’t know of a man on this fuckin’ earth that would have done less … . (Bozza, “Eminem: The Rolling Stone Interview” 72)29

And even after his divorce, he expresses consternation about his former spouse’s sexual behavior:

There’s a few things that are going to be tough to deal with … Kim is pregnant. I have no idea who the father is. I just know she’s due any day. So Hailie is going to have a baby sister. It’s going to be tough the day she asks me why her baby sister can’t come over. I’ve tried to keep her sheltered from those issues. (Bozza, “Eminem: The Rolling Stone Interview” 75)

As in the murder raps, Eminem positions himself as the good parent, Kim’s moral superior, aligned with the daughter against the insufficient mother. The world view expressed here assumes patriarchal privilege, privilege that undergirds misogyny, but that runs so deep in our culture that it often passes without notice. Their responses to his concert performances suggest that Eminem’s audiences share a similar world view. For example, one tour featured a segment in which Eminem acted out not spousal murder, but sexual domination on “Kim,” represented by an inflatable sex doll he insulted, sexually abused, then turned over to the audience for more abuse:

The world view expressed here assumes patriarchal privilege, privilege that undergirds misogyny, but that runs so deep in our culture that it often passes without notice. Their responses to his concert performances suggest that Eminem’s audiences share a similar world view. For example, one tour featured a segment in which Eminem acted out not spousal murder, but sexual domination on “Kim,” represented by an inflatable sex doll he insulted, sexually abused, then turned over to the audience for more abuse:

[A]t a concert in Portland, Oregon, Eminem told the crowd, “I know a lot of you might have heard or seen something about me and my wife having marital problems. But that s— is not true. All is good between me and my wife. In fact, she’s here tonight. Where’s Kim?” He then pulled out an inflatable sex doll, simulated an act of oral sex and tossed it to the crowd, which batted “Kim” around like a beach ball. (Gliatto 23)

While this doll is not the “real” Kim, it is her effigy, and the rapper’s indictment of her infidelity incites collective, symbolic violence against her: the scenario has less to do with beach blanket movies than it does with Old Testament stonings of accused adulteresses.

Misogyny for Fun and Profit

When journalists and fans take up the question of whether or not Eminem means what he says in his songs, they overlook a significant fact: neither of these murder ballads is an unmediated creation of a single individual. The lyrics of “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” were co-written with Marky and Jeff Bass, and both songs passed through the usual chain of production, promotion, and distribution.

It strikes me as odd to have remade the same subject into a new, more repugnant song, which compels me to wonder whether the decision to include “Kim” on The Marshall Mathers LP was influenced by record company executives with the objective of making Eminem’s second CD more sensational than the first. I suspect this for several reasons: first, it is a commonplace of recording industry wisdom that the second or “sophomore” album—a descriptor applicable here for so many reasons—often fails to live up to the popularity and profits of a successful debut. In the case of The Marshall Mathers LP, millions of dollars were poured into its production and promotion, apparently as insurance against sophomore failure (All Things Considered).30 Moreover, the general tone of The Marshall Mathers LP is more violent and sexist than The Slim Shady LP: rape is threatened or portrayed in three different songs, and women’s devalued status is particularly explicit in the refrain of the rap “Kill You”: “bitch, you ain’t nothing but a girl to me.”31 The postlude disclaimer, “Just playing, ladies; you know I love you,” does not undo the song’s vehemence and degradation.

As Tricia Rose has observed, “Rappers’ speech acts are … heavily shaped by music industry demands, sanctions, and standards” (101–103). The Marshall Mathers LP gestures toward this control from above in an interlude that simulates a conversation between Mathers and a record company representative, Steve Berman. Berman derides the rapper, calls his work “shit” and complains that he can’t sell it. “Do you know why Dr. Dre’s record was so successful? He’s rapping about big screen TVs, blunts, 40s, and bitches. You’re rapping about homosexuals and Vicodin.”32 During this “conversation,” the rapper is repeatedly interrupted and silenced. While such staged disputes do not represent actual conversations or accurately depict power relationships in the recording industry, they do contradict, even if fancifully, recording industry cant portraying Eminem as a creative artist exercising free expression in his raps: the likelihood that his “message” does not meet the approval of higher-ups is not very great. The skit also suggests, in accord with Tricia Rose’s claims, that sexism, although not all-pervasive among rappers, is part of the corporate culture of the recording industry (16).

A September 2001 news item about C. Michael Greene brings this issue into focus: According to the L.A. Times staff writer, an accusation of physical and sexual abuse by Greene against a NARAS employee was only “the latest in a string of harassment and discrimination complaints against Greene, several of which have been settled out of court,” and one of which led Rudolph Giuliani to ban the Grammy Awards in New York City after Greene allegedly threatened the life of one of the mayor’s female deputies (Philips C1). In spite of paying settlements and severance packages to the victims of Greene’s alleged harassment and discrimination, the NARAS board chose to retain Greene until recently, suggesting that they attributed little significance to this alleged behavior. Thus, Greene’s claim that NARAS nominated The Marshall Mathers LP for the Album of the Year Award to “recognize Eminem’s music but not his message,” is cynical and self-serving (All Things Considered).33

Personally abusive behavior aside, entertainment executives feel little compunction about churning out violent products based on misogynistic formulas when it means plumping the bottom line. For example, Susan Faludi has traced the genesis of the 1987 film Fatal Attraction from its origins as a short subject in which a married man is responsible for damaging both his marriage and the single woman he selfishly uses, to its final form as a tale of female sexual excess, of a predatory (and statistically anomalous) female stalker. A series of rewrites intended to shift blame from the male star (Michael Douglas) to the single woman (Glen Close) and production decisions informed chiefly by box office considerations culminated in an ending designed to please test audiences: the evil Other Woman is murdered by the Good Wife, often to cheering theater audiences (Faludi 116–135). And of course violence against women remains “good box office” in American opera houses as well: my favorite Puccini opera, La Fanciulla del West, about a brazen California cowgirl who successfully defends her outlaw man from the authorities, is seldom performed in this country, but Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and La Bohème, both of which feature the death of the heroine, are perennial crowd pleasers.

I do not intend to condone or excuse Eminem’s degradation of women, but rather to suggest that we see it against a background of entrenched institutionalized misogyny rather than as some phenomenon unique to Eminem or to rap as a genre. Significantly, the “clean” version of The Marshall Mathers LP, which bears no parental advisory and is sold at Wal-Mart, deletes the profanity and drug references, but does not alter the woman-hating sentiments (DeCurtis, “Eminem’s Hate Rhymes” 17–21).

The degree to which violence against women is accepted as normal in American culture is indicated by the haste with which it was dropped from the media coverage after the Grammys. Pre-Grammy coverage of the Eminem controversy on National Public Radio considered both homophobia and violence against women as serious issues. However, NPR’s day-after reportage of the rapper’s public relations duet with Elton John on the song “Stan” said nothing further about misogyny or spousal murder (National Public Radio). “Stan,” however, rehearses the very same trope while deflecting blame onto someone else: in this song, not Slim Shady, but rather an obsessive fan locks his pregnant wife into the trunk of a car then drives off a bridge.34 In coverage by other media, ranging from the left-wing institution The Nation to popular tabloid-style publications like Teen People, violence against women took a remote second place to concerns about homophobia, clearly an important and related issue, but one that comprises a smaller proportion of the content of these recordings than their pervasive degradation of women (Brown 35–8; see also Kim 4–5).

Writers in popular press magazines tend to make some obeisance to political correctness by remarking briefly on the misogyny of Eminem’s lyrics, but even these modest criticisms are neutralized by an overwhelmingly positive evaluation of Eminem’s talent, by incorporating the misogyny into an assessment of his “macabre imagination” (Toure 135–6) (which then makes it praiseworthy), or, my favorite tactic, by juxtaposing the criticism with lovey-dovey accounts of the rapper’s relationship with his daughter. Thus, Kris Ex’s review of The Eminem Show gives us the requisite misogyny paragraph,

His divorce from Kim Mathers fuels the slow Southern bounce of the hypermisogynist “Superman,” and his relationship with his estranged mother creates “Cleanin Out My Closet,” … [which includes] a list of atrocities and venomous threats … (108)

… immediately followed by, “Em’s love for his daughter, Hailie, produces his singing debut, the tender ‘Hailie’s Song’” (108). This type of journalism implies the same thing that Eminem’s songs do, that misogyny is a phenomenon driven by interpersonal relationships and justified by individual circumstances rather than a social blight for which Eminem happens to be a convenient representative: seldom do journalists question the implications of both his interviews and his murder raps, that Kim and mom are the “bad” women and Hailie the “good” one.

Even when her elder female relatives are not under discussion, journalists invoke Hailie in ways that seem to inoculate Eminem from his own degrading speech, as in this conversation about his fears of becoming a has-been:

Even when her elder female relatives are not under discussion, journalists invoke Hailie in ways that seem to inoculate Eminem from his own degrading speech, as in this conversation about his fears of becoming a has-been:

[Eminem:] Suddenly, you’re not cool no more, you’re like the Kris Kross jeans or something, even if at first you’re the greatest thing since sliced cunt.

[Rolling Stone:] Now that you have joint custody of Hailie, you’re spending more quality time with her. What’s a typical day like? (Bozza, “Eminem: The Rolling Stone Interview” 75)

Word choices like “sliced cunt” and “pregnant bitch” (hit in the stomach with luggage, quoted above) suggest that there is more to Eminem’s misogyny than his personal animus towards his wife or mother, but this subtlety seems to pass beyond the radar of the Rolling Stone writers.

Some sources completely elide the misogyny issue, for example EQ, a periodical for producers and audio engineers. Dr. Dre was their June 2001 coverboy—EQ rarely has a covergirl—and the interview article discussed his production techniques in The Marshall Mathers LP, which earned him a Best Producer Grammy. Considering the obvious care that Dr. Dre took to fit the raps with compelling accompaniments and sound effects, it is surprising that the article bears no mention of the lyrics (Roy 48–55). Foregrounding the technical aspects of music to the exclusion of text and narrative clearly parallels the situation Susan McClary has described with regard to formalist analysis of avant-garde music and its tendency to obscure misogynist content (McClary 57–81), and Dre’s own perspective is consistent with some of those McClary critiques. For example, he describes “Kim” [the song] this way: “It’s over the top—the whole song is him screaming. It’s good, though. Kim [the person] gives him a concept” (Bozza, “Eminem Blows Up” 72). Masculine creativity that is virtuosic, extreme, or “over the top” is the only issue of importance; Kim as concept is infinitely more significant than Kim as human being.

In magazines marketed to teenagers, Eminem’s misogyny is discussed in terms that make it seem coolly rebellious, as the reportage in the Summer 2001 Music Special issue of Teen People demonstrates. The overall tone of the coverage is celebratory: the magazine cover sports a large photo of Eminem surrounded by much smaller photos of other musical figures, and the controversies are presented in a carefully controlled manner under the title, “Rebel without a Pause” : “He has shocked parents, rocked the Grammys and divided his fellow musicians with his often inflammatory work. Can Eminem top himself? You bet.” Shortly follows a quote from one of his new tracks, cleverly titled, “I’ll s—t on you”: “A lot of people say misogynistic/Which is true/I don’t deny/Matter of fact, I’ll stand by it” (qtd. in Brown 36). “Misogyny” is not defined for these young teenage readers, many of whom will not know the word’s meaning.

Most disturbingly, under the rubric, “The Kids are All Right with Eminem,” appears the photo of a 13-year old girl, posing sexily in tight pants and midriff top, who opines that, although the song “Stan” makes her feel “disrespected as a girl,” “it’s great that [Eminem] says what he thinks about people … [and] doesn’t restrain himself” (qtd. in Brown 38). Conspicuously absent from Teen People is any allusion to the “disrespect” visited on girls in many recent concert audiences, from Woodstock ’99 (the scene of “rampant, horrifying sexual harassment,” eight rapes, and intimidation of any woman who would not remove her top) (Aaron 88–94), to the “Anger Management Tour,” where Eminem, Xzibit, and Ludacris, in series, greeted the “ladies” in the audience, received a friendly response, and then launched into raps with words like, “Bitch, you make me hurl” (Brackett 21–2).

The young teenage girls to whom this magazine is pitched can scarcely avoid grasping the message that it is “all right” for men to make them feel “disrespected as a girl” as long as those men are giving full expression to their untrammeled masculine subjectivity. And despite the fact that the valorization of limitless male subjectivity is like a bad hangover from nineteenth–century Romanticism, these girl readers will have every reason to believe that it is cool or at least normal because cultural products ranging from late night talk shows to music appreciation textbooks tend to agree.35

Resurrecting the Mother

Fig. 4. Tori Amos resurrects the mother: inside photo from Tori Amos, Strange Little Girls (Atlantic Recording Corporation, 2001) 7567-83486-2 Photo by Thomas Schenk.

One girl who is not “All Right with Eminem” is Tori Amos, whose 2002 CD, Strange Little Girls, includes a deconstructive intervention on “’97 Bonnie and Clyde.”The CD is a collection of covers of songs by male songwriters, all of which include the portrayal of some woman whose character Amos inhabits in the song: she re-imagines each song from a particular woman’s standpoint. The female characters are represented visually in portraits—all of them Amos—with captions—most of them cryptic.The picture for “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” seems to be an earlier photo of the now dead wife/mother, looking not at all like she’s “real, real bad,” but rather like an updated “Angel in the House” : long blonde hair, “natural” make-up, modest dress and affect, proffering a birthday cake (Figure 4). The caption reads, “She wonders what her daughter will do,” which is something that we all wonder at the end of the song.

If the resurrection of the mother and intrusion of Tori Amos’s feminine voice into Eminem’s narrative are not sufficiently disruptive, her flat, whispered delivery of the text, punctuated by a wailing refrain, chills to the bone (Example 5). At the end of the second strophe, she dwells on the text “me and my daughter,” and the synthesized accompaniment imparts a sense of the uncanny with its combination of excessive vibrato, portamentos, and obsessive low string ostinato: gone is Eminem’s danceable groove (although a snippet of clave rhythm is heard in the refrain) (Example 6). We come away from the recording knowing that spousal murder is no joke, and horror is even more evident in Amos’s stage performance: she sings the part of the woman from offstage, visually marking her erasure, the stage bathed in light—blood red.

Although Eminem’s murder ballad is at the center of Amos’s conception of Strange Little Girls, she applies her criticisms with a broader brush. In interviews she charges not only Eminem, but also other pop figures with cowardice and hypocrisy when they indulge in violent lyrics but then disavow them as “jokes.”36 Moreover, she remarks on the passivity of young women who, in their search for masculine approval, permit themselves to be degraded.37

The importance of Amos’s aim in this project—to give voice to silenced women and suppressed perspectives—is illustrated by some of her experiences in making the recording. To select songs for the CD, Amos consulted a “laboratory of men” who discussed what the various songs meant to them. Amos relates that, at first, most of the men did not want to discuss “’97 Bonnie and Clyde,” but then,

One man whom you’d consider very intelligent said, “You know, I have empathy for this guy [the murderer] because the [expletive] did this, did that and he just had enough and snapped.” The one thing that struck me was that not one of them asked about the wife. Nobody ever talked about her! (Harrington T06)

Even audiences who do not identify with the slayer, as did the man in Amos’s “laboratory,” tend to disregard the slain woman:

When I first heard the song … the scariest thing to me was the realization that people are getting into the music and grooving along to a song about a man who is butchering his wife. So half the world is dancing to this, oblivious, with blood on their sneakers. (Atlantic Records)

One person who is not dancing, Amos points out, is the woman in the trunk (vanHorn).

Amos’s version of “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” is stunning not only because it exposes the horror embedded in Eminem’s jolly little tune, but also because it challenges us to listen for the voice of that woman in the trunk, and this strikes at the very heart of patriarchy. For once we acknowledge that there are other voices to be heard, and we make the effort to hear them (not their ventriloquized simulations), we have disrupted the unspoken assumption that the only subject position that matters is male, that women are disposable, and that it is “all right” to construct culture over our dead bodies.

***

Versions of this paper were presented at the Feminist Theory and Music 6 conference at Boise State University in July 2001, at the Southern Chapter meeting of the College Music Society at Union University in February 2002, and at the annual meeting of the Society for American Music at the University of Kentucky in March 2002. I wish to thank all of those who gave me valuable feedback in the stimulating discussions that followed these presentations. I also thank Chad Jones, my graduate student at the University of Tennessee, for his invaluable assistance.

***

Elizabeth L. Keathley received her Ph.D. in Music from the State University of New York at Stony Brook, where she also earned an Advanced Certificate in Women’s Studies. Her articles on Schoenberg, modernism, and gender have appeared in the U. S. and in Europe. Keathley is an Assistant Professor in Music History at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

***

Works Cited

Aaron, Charles. “Rap-rock Mooks.” Spin (January 2000): 88–94.

Abel, Elizabeth, Marianne Hirsch, and Elizabeth Langland, eds. The Voyage In: Fictions of Female Development. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1983.

All Things Considered. Narr. Rick Karr. National Public Radio News. 20 February 2001.

American Bar Association. Legal Interventions in Family Violence: Research Findings and Policy Implications. Research Report. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1998. NCJ 171666.

Atlantic Records. Press Release. “Tori Amos: ‘Strange Little Girls’—New Album Due In Stores Sept. 18.” 2 July 2001. Accessed 15 August 2002 http://www.thedent.com/pressrelease070201.html.

Baer, Deborah. “Tori Amos interview.” CosmoGIRL (October, 2001): Accessed 8 September 2002 http://www.thedent.com/cosmogirl1001.html.

Blau du Plessis, Rachel. Writing beyond the Ending: Narrative Strategies of Twentieth-century Women Writers. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Bozza, Anthony. “Eminem Blows Up.” Rolling Stone 811 (29 April 1999): 42–47.

—. “Eminem: The Rolling Stone Interview. The loose-lipped rapper isn’t afraid of his demons. Should you be?” Rolling Stone 899/900 (4–11 July 2002): 70–76.

Brackett, Nathan. “Slim’s Circus.” Rolling Stone 903 (22 August 2002): 21–2.

Brown, Ethan. “Rebel without a Pause.” Teen People (Summer 2001): 35–38.

Chin, Rob. Rev. of Sanctuary. “Pet Shop grab bag: the Pet Shop Boys’ latest is a hit-and-miss affair accentuated by their love song to Eminem.” The Advocate (11 June 2002): 63.

Clément, Catherine. Opera: or, The Undoing of Women. Trans. Betsy Wing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

Cockrell, Dale. Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and their World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Coker, Cheo Hodari. Rev. of The Marshall Mathers LP. Vibe (August 2000): 162. Qtd. in TowerRecords.com. Accessed 18 July 2001 http://www.towerrecords.com/product.asp?pfid=1863588&cc=USD&from1=pul. [Link Broken]

Daly, M., and M. Wilson. “Evolutionary Social Psychology and Family Homicide.” Science 242 (1988): 519–524.

Davis, Angela Y. Women, Race and Class. New York: Random House, 1981.

DeCurtis, Anthony. “Eminem’s Hate Rhymes.” Rolling Stone 846 (3 August 2000): 17–21.

—. “Eminem responds: The rapper addresses his critics.” Rolling Stone 846 (3 August 2000): 18.

Domestic Violence Information Center, Feminist Majority Foundation. “Domestic Violence Facts.” Accessed 21 July 2001 http://www.feminist.org/other/dv/dvfact.html.

Ex, Kris. “The Eminem Show: Elvis Re-enters the Building as Eminem Masters his Own Show.” Rolling Stone 899/900 (4–11 July 2002): 107–8.

Faludi, Susan. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. New York: Crown Publishers, 1991.

Felski, Rita. Beyond Feminist Aesthetics: Feminist Literature and Social Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Freedom du Lac, Josh. Rev. of The Marshall Mathers LP. “Eminem: Disturbed Mind, Mad Talent.”Pulse! Magazine. TowerRecords.com Accessed 18 July 2001 http://pulse.towerrecords.com/contentStory.asp?contentId=434&artistId=357. [Link Broken]

George, Nelson. Buppies, B-Boys, Baps & Bohos: Notes on Post-soul Black Culture. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

Gliatto, Tom, et al. “Sugarless Eminem: With two arrests and his wife Kim’s suicide attempt, the controversial rap star faces a rocky road.” People Magazine (24 July 2000): 139ff.

Harrington, Richard. “Tori Amos Flips the Perspective.” Washington Post 5 October 2001, late ed. weekend: T06. Accessed 15 August 2002 http://www.thedent.com/washpost100501.html.

Hermes, Will. “Don’t Mess with Mother Nature.” Spin Magazine (October, 2001): Accessed 8 September 2002 http://www.thedent.com/spin1001.html.

Holland, Bill. “Protests Follow Eminem Nominations.” Billboard (20 January 2001): 102.

hooks, bell. Salvation: Black People and Love. New York: William Morrow, 2001.

James, Etta, and David Ritz. Rage to Survive: The Etta James Story. New York: Villard Books, 1995. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998.

Kaplan, E. Ann. Introduction. Women in Film Noir. Ed. E. Ann Kaplan. Rev. Ed. London: British Film Institute, 1980. 1–5.

Kelley, Robin D. G. “Kickin’ Reality, Kickin’ Ballistics: Gangsta Rap and Postindustrial Los Angeles.” Droppin’ Science: Critical Essays on Rap and Hip Hop Culture. Ed. William Eric Perkins. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996. 117–158.

Kim, Richard. “Eminem—Bad Rap?” The Nation (5 March 2001): 4–5.

Krims, Adam. Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Leo, John. “Lovely Monsters.” U.S. News and World Report (5 March 2001): 14.

Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

McClary, Susan. “Terminal Prestige: The Case of Avant-garde Musical Composition.” Cultural Critique 12 (Spring 1989): 57–81.

Mitchell, Tony. “Introduction: Another Root: Hip-Hop outside the USA.” Global Noise: Rap and Hip-Hop Outside the USA. Ed. Tony Mitchell. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1994. 1–38.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16.3 (Autumn 1975): 6–18.

National Center for Women and Policing. “Equality Denied: The Status of Women in Policing: 1999.” Accessed 21 July 2001 http://www.WomenandPolicing.org/statusreports.html.

National Organization for Women. “NOW Information on the Promise Keepers.” http://www.now.org/issues/right/pk.html. [Link Broken]

National Public Radio News, 22 February 2001.

Orenstein, Peggy. School Girls: Young Women, Self-Esteem, and the Confidence Gap. New York: Anchor Books, 1994.

Pareles, Jon. Rev. of The Eminem Show. “Eminem III: Now He’s a Franchise.” The New York Times 2 June 2002, late ed.: 2.1.

Perkins, William Eric. “The Rap Attack: An Introduction.” Droppin’ Science: Critical Essays on Rap and Hip Hop Culture. Ed. William Eric Perkins. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996. 1–45.

Peterson-Lewis, Sonja. “A Feminist Analysis of Defenses of Obscene Rap Lyrics.” Black Sacred Music 5.1 (Spring 1991): 68–79.

Philips, Chuck. “Sex Harassment Claim Against Grammy Chief; Music: Academy is looking into accusations by a female human resources executive that she was assaulted by C. Michael Greene.” Los Angeles Times 11 September 2001: C1.

Place, Janey. “Women in Film Noir.” Women in Film Noir. Ed. E. Ann Kaplan. Rev. Ed. London: British Film Institute, 1980. 35–54.

Prince, Stephen. “Graphic Violence in the Cinema: Origins, Aesthetic Design, and Social Effects.” Screening Violence. Ed. Stephen Prince. Rutgers Depth of Field Series. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000.

Richtel, Matt. “CD Becomes No. 1 Before its Release.” The New York Times 3 June 2002, late ed.: C4.

Rose, Tricia. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1994.

Roy, Lisa. “Don’t Forget about Dr. Dre: The Production Secrets of Grammy Award Winner, Dr. Dre.”EQ: Professional Recording and Sound (June 2001): 48–55.

Samuel, Anselm. Rev. of The Marshall Mathers LP. The Source (August 2000): 225–6. Qtd. inTowerRecords.com. Accessed 18 July 2001 http://www.towerrecords.com/product.asp?pfid=1863588&cc=USD&from1=pul. [Link Broken]

Shaw, William. West Side: Young Men and Hip Hop in L.A. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000.

StopFamilyViolence.org. “Family Violence Statistics.” Accessed 28 July 2001 http://www.stopfamilyviolence.org/sfvo/statistics.html. [Link Broken]

Strauss, Neil. “Grammys Chief Quits under Fire.” New York Times 29 April 2002, late ed.: E1.

Tessier, Marie. “Battered Woman’s Advocate Murdered by Companion.” Women’s Enews Posted 19 September 2002. Accessed 19 September 2002 http://www.womenenews.org. [Link Broken]

Thigpen, David E. “Raps, in Blue: Eminem rings up sales as well as controversy.” Time 153.13 (5 April 1999): 70.

Tjaden, Patricia, and Nancy Thoennes. Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, D.C.: U. S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000. NCJ181867. Accessed 12 July 2001 http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov. [Link Broken]

Toure. Rev. “Eminem: The Marshall Mathers LP.” Rolling Stone 844/845 (6–20 July 2000): 135–136.

vanHorn, Teri. “Tori Amos Says Eminem’s Fictional Dead Wife Spoke To Her.” MTV.com Posted 28 September 2001. Accessed 15 August 2002 http://www.thedent.com/mtvart0901.html.

Walters, Barry. “Up in Smoke Tour.” Rolling Stone 846 (3 August 2000): 23.

White, Armond. “Who Wants to See Ten Niggers Play Basketball?” Droppin’ Science: Critical Essays on Rap and Hip Hop Culture. Ed. William Eric Perkins. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996. 192–208.

Discography

Amos, Tori. Strange Little Girls. Atlantic Records, 2001.

D12. Devil’s Night. Interscope Records, 2001.

Eminem [Marshall Mathers]. The Eminem Show. Interscope Records, 2002.

—. The Marshall Mathers LP. Interscope Records, 2000.

—. The Slim Shady LP. Interscope Records, 1999.

- Murders by jealous boyfriends/husbands are thematized in Otello, Wozzeck, Carmen, Symphonie Fantastique; rape/killing by authority figures in Salome, Philomel; death after seduction and abandonment or forced marriage in Norma, Lucia di Lammermoor, Faust, Rigoletto, Madama Butterfly; virgin sacrifice in the Rite of Spring; death by TB in La Traviata and La Boheme. ↩

- While Clément’s critique addressed primarily nineteenth–century opera, some music history sources have projected this violent obsession back into earlier historical periods by dwelling luridly on Gesualdo’s murder of his wife and her lover, apparently with the aim of rationalizing the chromatic excess and morbid tone of his compositions. ↩

- Many bluegrass murder ballads are adapted from vernacular songs with origins in the British Isles. I call the two rap songs under discussion here “murder ballads” because their premises and narrative content are so similar. ↩

- I do not wish to argue that the misogyny of gangsta rap is somehow benign. For example, Dr. Dre (Eminem’s producer) not only recorded rap songs that depicted violence against women (for example, the notorious “One Less Bitch”), but also verbally and physically attacked (female) video show host Dee Barnes in retaliation for a perceived insult—see Rose 178–9 and Kelley 145. Significant discussions of violence in gangsta rap appear in Kelley, Rose, and George. Importantly, Rose and others argue that the way that “violence” has been defined and discussed with regard to rap music has tended to ignore forms of institutionalized violence directed at the black urban working class. ↩

- “Homies,” or “homeboys” are friends and acquaintances from one’s own neighborhood. The sense of place is important in rap music, and Eminem’s black homies—most clearly evidenced by his all-black posse in D12, his other rap act—help to locate his urban Detroit residence. It was Eminem’s performance in one MC battle, the Rap Olympics, that brought him to the attention of Dr. Dre. This event is described in Shaw 81–3. Of the “previous white rappers” I have in mind Vanilla Ice, whose “ghetto credentials” were falsified, and the Beastie Boys: they and others are discussed in White 192–208. ↩

- See also Samuel. ↩

- Eminem acknowledges both his privileged status and his comparison to Elvis: on his new CD, The Eminem Show, he raps these lyrics, “I am the worst thing since Elvis Presley … To do black music so selfishly/And use it to get myself wealthy,” and “if I was black, I woulda sold half” (from the track “White America”). These lyrics are quoted in Ex’s Rolling Stone review of The Eminem Show. The rapper echoes this sentiment in interviews: “It’s obvious to me that I sold double the records because I’m white. In my heart I truly believe I have a talent, but at the same time I’m not stupid” (Bozza, “Eminem: The Rolling Stone Interview” 76). ↩

- See especially Cockrell, Chapter 2 “Blackface in the Streets” 30–61. ↩

- Lott is describing the ambiguous racial operations of minstrelsy in these passages, not rap or Eminem. ↩

- Kelley gives a persuasive and nuanced account of the construction of black ghetto masculinity in gangsta rap in “Kickin’ Reality” 136–140, and also makes clear what is at stake in these constructions, given stereotypes of black male criminality and the alarming rates of incarceration of young black men. In her now classic text, Women, Race and Class, Angela Y. Davis addressed some of these stereotypes in the essay, “Rape, Racism, and the Myth of the Black Rapist”: while slave owners’ rape of black women was suppressed in most discussions of the slave economy, false accusations of black men raping white women served the agenda of lynching and impressed on the popular imagination the image of black men as brutal sexual predators. Black feminists have raised objections to the sexual brutality of much gangsta rap not only because it degrades black women, but also because it keeps in circulation these violent stereotypes of black men. See, for example, Peterson-Lewis. ↩

- I don’t intend to imply racism on Eminem’s part; to the contrary, he imagines himself as a force for racial equality. As he opined in an August 2000 interview, “ … nobody wants to talk about the positive shit I’m doing. There’s millions of white kids and black kids coming to the tour, throwing their middle fingers up in the air, and all having the common love—and that’s hip-hop” (DeCurtis, “Eminem Responds” 18). It is not exactly my vision of racial harmony, but I see his point. ↩

- An exclusively male organization, The Promise Keepers is the fastest growing movement of the Christian right. Their raison d’être is to reverse the corrupting feminization of society beginning with the home, where men are urged to reclaim their rightful place at the head of the household, and their wives are urged to submit to male leadership. The group is bankrolled by such right-wing notables as Jerry Falwell and has ties to organizations like Focus on the Family and Operation Rescue. The membership consists mostly of working-class white men, like Eminem. See The Promise Keepers website www.promisekeepers.org, but also the National Organization for Women’s page http://www.now.org/issues/right/pk.html. Although conservatives, by and large, voice disapproval of Eminem’s offensive lyrics, in the conservative U.S. News and World Report, John Leo attributed Eminem’s violence to rebellion against “political correctness” (14). Not to put too fine a point on the cultural diversity of patriarchy in rap music, the Palestinian rap group Shehadin (Martyrs) expresses their moralistic stance in such songs as, “Order Your Wife to Wear a Veil for a Pure Palestine.” See Mitchell 9. ↩

- The numbers of male victims of intimate partner homicide have dropped sharply during that period (See Tessier). ↩

- Musicologists are most familiar with these operations due to the work of Catherine Clément and Susan McClary, but feminist literary scholars have shown that the “transgression and punishment” paradigm was the dominant one for literature of the nineteenth century with a female protagonist. See, for example, Blau du Plessis Writing beyond the Ending: Narrative Strategies of Twentieth-century Women Writers, and Abel, Hirsch, and Langland, eds., The Voyage In: Fictions of Female Development. Both sources are cited by Felski, Beyond Feminist Aesthetics: Feminist Literature and Social Change. Similarly, Mulvey has shown that the spectacle of women’s suffering is a source of visual pleasure in cinema in her germinal text “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” ↩

- Men who have murdered their wives report that the wife’s separation or threat of separation precipitated the murder. See Tjaden and Thoennes 37; these authors cite Daly and Wilson, “Evolutionary Social Psychology and Family Homicide.” ↩

- Sampled sound effects are common in gangsta raps; more on this in note 19, below. ↩

- It is Bill Withers’ vocal on this recording, but the hit is attributed to Grover Washington, Jr. “Just the Two of Us” is also a track on Will Smith’s Big Willie Style CD, a sentimental father-and-son number. Some reviews of The Slim Shady LP have suggested that “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” satirizes Smith’s work. See, for example, Thigpen 70. ↩

- “Ultraviolence” is Prince’s term. In her memoir, Rage to Survive, Etta James also uses “Bonnie and Clyde” to describe herself and her partner during a spree of crime and drug-taking. The exact nature of the relationship between cinema and rap music is beyond the scope of this essay, but it is apparent that some rappers draw on the images of 1970’s “Blaxploitation” films, among a large number of other cultural artifacts, and that many of the raps with narrative content use sound effects to create an analog to cinema, with results that Kelley has called “audio verité” (136). Titles like the Sporty Thievz’s CD Street Cinema are also suggestive. ↩

- The lyrics for “‘97 Bonnie and Clyde” were written by Mathers with Marky and Jeff Bass; the track was produced by Marky and Jeff Bass. ↩

- The “two more things” in the trunk are the bodies of the wife’s new husband and stepson. An American Bar Association study found that “victims of violence rarely seek restraining orders as a form of early intervention, but rather as an act of desperation after they have experienced extensive problems.” Sixty percent of women in the ABA study reported that the restraining order was violated within one year of its issue (Tjaden and Thoennes 53, 54 n. 1). Tjaden and Thoennes cite the American Bar Association, Legal Interventions in Family Violence: Research Findings and Policy Implications. Because of their methodology—interviews with living persons—Tjaden and Thoennes do not give statistics for spousal murder. ↩

- On average, respondents to Tjaden and Thoennes’s study reported multiple spousal abuses over a period of 3.8 or 4.5 years, depending on the type of abuse (rape or physical assault) (39). Victims reported lower rates of rape and physical abuse and higher rates of stalking after having left their intimate partners (Tjaden and Thoennes 37–8). ↩

- The most recent statistics demonstrate that stalking is more prevalent than previously thought and that more women than men are stalked by intimates; they “suggest that intimate partner stalking is a serious criminal justice problem” (Tjaden and Thoennes iii). For information on domestic violence, including stalking, see: National Center for Women and Policing; Domestic Violence Information Center, Feminist Majority Foundation; and StopFamilyViolence.org. ↩

- Creepily, Hailie Mathers’ real voice is heard in “’97 Bonnie and Clyde,” and she is the child in the CD photographs, including one inside the CD booklet where she looks forlornly into the trunk (Bozza, “Eminem Blows Up” 42–47). ↩

- “Eminem,” is, obviously, a stage name, derived from the initials of “Marshall Mathers,” the rapper’s given name. “Slim Shady” is a criminal character who appears frequently as the narrative “I” in Eminem’s raps. This triad of personae is one way that Mathers is able to distance himself from the content of his raps since, ostensibly, Slim Shady “does” things that Eminem “wouldn’t do,” and “Eminem” “does” things that Marshall Mathers “wouldn’t do.” The distinctions among these personae are part of the defense of Eminem’s work, as Michael Greene has maintained: “The kids laugh at us—they know what this is—it’s theater” (as opposed to reality) (qtd. in Holland 102). The distinctions among these personae blur, however: Mathers has a large “Slim Shady” tattoo on his upper left arm, and he, like many rappers, has been arrested for gun-related violence in apparent imitation of his own musical fantasies. ↩

- Eminem plays up the slasher film analogy with sometime concert props (a hockey mask and a chainsaw), and there were plans to market an Eminem action figure in the same garb (Brown 35–38). ↩

- Rose discusses extensively the “dialogism” of rap’s gender politics in Chapter Five of Black Noise. Krims also makes mention of this process in Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity 121. I do not mean to suggest that the rap songs under discussion here are in any way unique instances in their control of the fantasy. ↩

- Nearly every track on The Marshall Mathers LP contains some element of self-pity, from Mathers’ upbringing to oppression by the recording industry, to the pressures of celebrity. Examples include “Kill You,” “Stan,” “Who Knew,” “Steve Berman,” “The Way I Am,” “The Real Slim Shady,” “I’m Back,” “Marshall Mathers,” and on and on and on. While some may regard this as self-parody—and I would agree that Eminem’s willingness to hold himself up to parody is something that distinguishes him from most other rappers—the message that bad things happened to him, and that he is (therefore) not accountable for the consequences of his own words comes across quite clearly. ↩

- Eminem is presently on probation for two weapons charges from 2000 (one was the stalking incident). Both his mother and his ex-wife have sued him for defamation, and his wife attempted suicide before filing for divorce. These events are summarized, somewhat prejudicially, in Bozza, “Eminem: The Rolling Stone Interview.” More gossipy in tone, but more sympathetic to Kim, is the account in Gliatto 139ff. ↩

- The editor’s addition in the square brackets is from Rolling Stone, not from me. ↩

- This media blitz included a weekend devoted to “Em TV” on MTV. The Slim Shady LP sold over three million copies (triple platinum), and The Marshall Mathers LP shot to number one on the Billboard charts in its first week with 1.8 million. ↩

- “Girl” is also used as an insult on Devil’s Night in the song “Girls,” where Eminem disses Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst. ↩

- “Steve Berman,” with Steve Berman, The Marshall Mathers LP. Similar skits with Steve Berman appear on Eminem’s album with his posse D12, Devil’s Night and The Eminem Show. In the latter skit, Berman is shot. ↩

- Greene has recently resigned. According to Neil Strauss of the New York Times, he announced his resignation at a 27 April 2002 “meeting of the academy’s board … called to discuss the organization’s investigation of a sexual harassment lawsuit against Mr. Greene” (E1). ↩

- Several critics have commented on the barely concealed homoeroticism of this song, particularly Stan’s line “We should be together.” See Kim. The Pet Shop Boys’ “The Night I Fell in Love” (Sanctuary, 2002) quotes that line in the context of “a gay youth’s fantasy tryst with a hip-hop performer.” See Chin 63. ↩

- I suspect that this willingness to be disrespected has a great deal to do with the well-documented decline in self-esteem of teenage girls. See Orenstein, School Girls: Young Women, Self-Esteem, and the Confidence Gap, written under the auspices of the American Association of University Women. ↩

- See, for example, Tori Amos’s interview with Will Hermes. ↩

- See, for example, Tori Amos’s interview with Deborah Baer. ↩