Timothy D. Taylor1

The greatest advertising medium in the world is radio.

—Rudy Vallée, 1930

Music has power. Musicians know it, listeners know it. And so do advertisers. The story here begins with the early history of broadcasting immediately following the first burst of radio’s popularity. It will examine how this new communications technology became conceptualized and employed as an advertising medium.2 This essay charts the slow rise of radio advertising through the subsequent processes of informing reluctant advertisers of radio’s usefulness, translating print advertising techniques into sound, and the debates over which music to use in broadcast advertising. There is also a consideration of two programs, the early Aunt Jemima, and the popular and long-running Fleischmann Hour with Rudy Vallée.

Before proceeding, however, it must be understood that the rise of radio—and advertising—can only be grasped in a larger framework of changing patterns of American consumption. This is a topic of growing interest among scholars (with important recent books by Gary Cross and Lizabeth Cohen, among others), so this is only the briefest of introductions. Simply put: mass production necessitated a rise in wages that allowed workers to participate in the economy as consumers. Coupled with this development, the increasing banalization of work with the implementation of Taylorist and Fordist models of management and production also meant that the consumption of goods and services came to occupy a larger role in American life. As American workers were transformed into consumers, the old American ideals of thrift and self-sacrifice ceased to serve an economy that increasingly demanded spending (Rubin 24). To quote one observer from 1935: “As modern industry is geared to mass production, time out for mass consumption becomes as much a necessity as time in for production” (Ware 101).

The growth of consumption in this period was aided by changes in American spending habits: the practice of credit rose, and the use of the installment plan accelerated greatly in the beginning of the 20th century.3 Settings of consumption increased the allure of purchased goods, as department stores became increasingly like churches, temples of consumption (Cross 29).4 And of course, advertising, a young field in the early part of the 20th century, was instrumental in shifting Americans toward this new mode of consumerism.

Advertisers were well aware of their mission, which they conceived of not simply as selling goods, but as promoting the idea of consumption itself. The influential trade magazine Printer’s Ink said in 1923 that advertising was a means of efficiently creating consumers and homogeneously “controlling the consumption of a product” (“Senator” 152, quoted by Ewen 33). An entry in The Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences in 1922 said that “what is most needed for American consumption is training in art and taste in a generous consumption of goods, if such there can be. Advertising is the greatest force at work against the traditional economy of an age-long poverty as well as that of our own pioneer period; it is almost the only force at work against Puritanism in consumption” (Lyon 475, quoted by Ewen 57). Advertising, to put it bluntly, was viewed by its practitioners and proponents as a force of modernization, designed to obliterate “customs of ages,” to remove “the barriers of individual habits of limited thinking.” Advertising viewed itself as “at once the destroyer and creator in the process of the ever-evolving new. Its constructive effort [was] … to superimpose new conceptions of individual attainment and community desire” (Hess 211).

Selling Radio to Advertising Agencies

Selling and buying were thus the order of the day in the 1920s. Radio, in effect, was sold to the American public. Just as radio aficionados, the radio industry, and broadcasters had educated the general public about the potential benefits of radio, advertising agencies and sponsors had to be appealed to as well.5 When public awareness of radio emerged in the mid-1920s, advertising agency Radio Department staff members devoted much of their time to informing their clients about what radio, and advertising on the radio, was all about. They had to promote radio to their colleagues who had learned advertising as a print business, and who saw themselves as rather highbrow, especially at the J. Walter Thompson Company, the biggest company in America at the time; Stanley Resor, who with others had purchased the company from Thompson himself in 1916, was the first head of a major advertising firm who had a college degree, and his was from Yale. To Resor and others in the advertising industry, radio was not simply unknown and chancy compared to print advertising, it ran the risk of being offensive in that it was difficult to ignore, since the consumer could not simply turn the page as in a print ad. (The J. Walter Thompson Company will be the focus of much of the following discussion because of the availability and usefulness of its archives).

The Thompson Company staff meeting minutes reveal a good deal of proselytizing on behalf of radio by members of the agency’s newly-formed radio department. The first head of this department, William H. Ensign, defended radio to his bosses and colleagues in the meeting of July 11, 1928. Ensign began his report by saying that “as far as J. Walter Thompson is concerned, the latest developments are along lines of loss of ground rather than making progress as far as billing is concerned,” because two of its clients had decided to cancel most of their radio programs. Ensign nonetheless defended the new medium: radio was not the problem, but the clients’ cold feet, and once new sales data were in, the clients could be urged to resume broadcasting. Ensign went on to mention broadcasting plans for other clients, and then introduced his main evidence in favor of radio: that “15 national advertisers and 6 semi-national or local have entered the ranks of broadcast advertisers” in the previous six months, and he included a list of Thompson competitors who had started radio departments (J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, Box 1, Folder 5).

Attempts to convince colleagues continued in other company venues. J. Walter Thompson’s News Letter from September 15, 1928, displayed on its first page an article by one of the company’s first radio program producers, Gerard Chatfield, who was a classically-trained musician formerly employed by the National Broadcasting Company. He began his article, “Advertising Agency Should Recognize and Use Radio,” by writing that “radio broadcasting has become a major medium in record-breaking time. It should be considered as such and not as a freakish mystery, a plaything or an experiment. It is simply another means of gaining entrance into approximately 10,000,000 of the most prosperous homes in the United States” (Chatfield 1). These homes were the most prosperous because radio was still something of a luxury item for many families in this period.

In the staff meeting of April 3, 1929, Henry P. Joslyn (who had succeeded Ensign the previous month) provided several examples of how music had been used on the air to sell products. His first and best example concerned the Lucky Strike Hour, described as a “straight jazz program of dance music, interspersed with the reading of anti-fat testimonials taken from the printed advertising,” read by the announcer. No famous jazz orchestra was hired, “no name, such as Paul Whiteman, was used to make this campaign stand out.” No gimmicks. George Washington Hill, the imperious president of Lucky Strikes’ parent company, American Tobacco Company, wrote to the president of the National Broadcasting Company, which aired the program, to say that sales went up in excess of 47 percent, an impressive figure since the American Tobacco Company had suspended most of their other advertising during a two-month trial period of advertising on the radio.6

Joslyn also listed some “local” examples, such as the so-called “spot” advertisements that aired on one station with a link, or what was called a tie-in, to a local dealer or local product. An example is Dr. Strasska’s Toothpaste, which sponsored a program in Cleveland featuring a Mr. [Charles W.] Hamp, “who sang, played instruments, cracked jokes and otherwise stirred up the air for twelve weeks during the dinner hour,” every day. Joslyn and John Ulrich Reber, who was soon to replace Joslyn as head of the Radio Department, both agreed that the show was terrible, and that Hamp “has no particular form or class.” This ultimately did not matter, however, because “the people who buy toothpaste like it.” The radio show, combined with a program in some department stores that gave away free samples of the then-unknown toothpaste, resulted in 8,412 requests for samples; local stores sold 47,500 tubes (J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, Box 1, Folder 7).

Erik Barnouw writes that in a June 1932 issue of Chain Store Management magazine, the Kellogg Company told its dealers how merchandising through the Singing Lady program, a children’s show, was working:

Just think of this: 14,000 people a day, from every state in the Union, are sending tops of Kellogg packages to the Singing Lady for her song book. Nearly 100,000 tops a week come into Battle Creek. And many hundreds of thousands of children, fascinated by her songs and stories and helped by her counsel on food, are eating more Kellogg cereals today than ever before. This entire program is pointed to increase consumption—by suggesting Kellogg cereals, not only for breakfast but for lunch, after school and the evening meal. It’s another evidence of the Kellogg policy to build business—and it’s building (quoted by Barnouw 26).

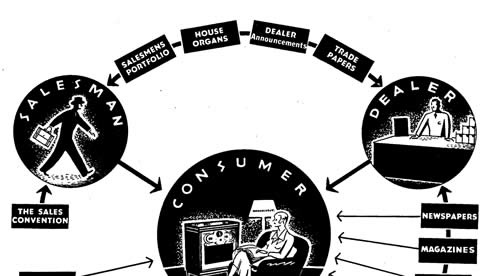

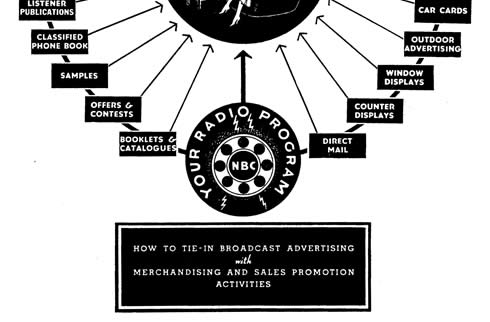

Spot and national advertisements frequently had a “tie-in,” often simply a plain poster or print ad, and frequently more. A brochure about Ipana Toothpaste produced by NBC in 1928 included photos of the tie-ins that Ipana provided to customers who wrote in: a “Magic Radio Time Table” pad, so that listeners could write down their favorite programs; a bridge score card; a photo of the Ipana Troubadours, the program’s resident musicians; a card with a paean to the smile. All of these items had the Iapana name prominently displayed. Then there was the tie-in material made available to dealers: posters, brochures, a “radio applause card” that listeners could take to send in comments on the program, and more (National Broadcasting Company, Improving the Smiles of a Nation!).7 By the mid-1930s, consumers could be positively bombarded by advertisers, as the figure below shows.

In this figure, the sponsored radio program is represented as the central advertising force, surrounded by an array of various modes of print advertising and tie-ins. NBC is obviously emphasizing the idea of the centrality of radio broadcasting, and also providing a useful diagram for how consumerism was entering the home, and American culture more generally, via every conceivable avenue.

Just as radio men—and they were mostly men—in advertising agencies sold radio to their colleagues, networks proselytized for radio among advertisers, potential sponsors of programs. Broadcasters, who made their income primarily by providing facilities and leasing airtime, were thus constantly wooing advertisers. A document produced by NBC in 1929 stated boldly that “because Broadcast Advertising appeals to the prospective purchaser through the medium of his ear instead of his eye, it acts on him in a subconscious manner, supplementing all other advertising to him” employing language from psychology that increasingly found its way into advertising discourse following World War I (National Broadcasting Company, Broadcast Advertising: A Study of the Radio Medium 25).

NBC and its younger, upstart rival, the Columbia Broadcasting System, produced countless lavish brochures on products such as Ipana toothpaste, as well as programs, stars, and their overall stable of entertainers in order to hype themselves to potential advertisers.8 I will examine some of these below. First, however, some discussion of the early history of radio is necessary to lay the groundwork for considerations of music on the air.

From Print to Radio, Eye to Ear

At the beginning of radio there were countless debates about how it would be funded (just as there was at the beginning of the Internet). It was a convoluted and arduous journey to advertising as the solution, yet advertising quickly became so dominant that networks in this period did little more than provide studio space and lease airtime, and produce some programs, called “sustaining programs” (usually high-prestige shows such as the NBC Music Appreciation Hour, with conductor Walter Damrosch); many programs were produced by advertising agencies in this period.9 Because of this production arrangement, it is virtually impossible to separate early radio broadcasting from advertising. So, at least from the 1920s into the early 1930s, a history of music and broadcast advertising is less about ads and jingles than programs themselves, into which ads were built.

Even though advertisers eventually triumphed in their pursuit of a funding mechanism for radio programming, early advertisers were extremely reluctant to embark on hard-sell campaigns, preferring to treat the new medium gingerly; advertising agencies were wary of crass sales in the home. Between 1922 and 1925, Printer’s Ink railed against radio as an “objectionable advertising medium” (perhaps in part because the editors focused on publishing). The journal emphasized the dangers of creating public ill will: “The family circle is not a public place, and advertising has no business intruding there unless it is invited” (quoted in McLaren and Prelinger). Sponsoring a program could bring good will, but advertisers feared that an intrusive sales pitch might alienate listeners. And there was governmental pressure against too much advertising: in 1922, Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce and the government official who oversaw broadcasting, said that it was inconceivable that the airwaves be “drowned in advertising chatter” (quoted in Marquis 387).

Thus, the first model of broadcast advertising emphasized goodwill: sponsored programs were developed to generate goodwill in the audience, whose members, it was hoped, would purchase the products advertised out of gratitude to the sponsor for providing the program. This idea of goodwill seems to have been fairly successful at first. Not only did sales of sponsors’ products rise, but audience members wrote in to sponsors to express their appreciation. The trade press published some of these letters. “It may interest you to know,” wrote a listener from Philadelphia to the Whittall Rug Company, sponsor of the Whittall Anglo-Persians (an orchestra conducted by Louis Katzman that played standards and an occasional “oriental” work) “as a result of the Whittall Anglo-Persian concerts, which are enjoyable to no ordinary extent, we have just purchased three large and two small Anglo-Persian rugs. Otherwise and as heretofore, we would have ‘shopped around’ ” (“Radio’s Magic Carpet,” 26).10

The advertising that did find its way into programs was referred to as “indirect advertising,” which worked by incorporating a message or two in the program, often including the product name in the program title, as well as the name of the band or orchestra, sometimes even insinuating the product into the names of the performers. The Palmolive Hour, which aired from 1927-1931, for example, featured singers “Olive Palmer” (whose real name was Virginia Rea) and “Paul Oliver” (real name Frank Munn). “The naming of the musical unit in such a way that the company’s name can be included with each entertainment announcement is psychologically sound,” wrote P. H. Pumphrey, manager of the Radio Department of Fuller, Smith & Ross, Inc. “When the listener hears that ‘The Lucky Strike Dance Orchestra now plays Baby’s Birthday Party,’ or that ‘Erno Rapee and his General Electric Orchestra will bring us the finale from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony,’ the commercial name registers, but except to the most captious, does not appear as an intrusion” (Pumphrey, “Writing and Casting,” 42). Such a practice denied many musicians the opportunity to perform under their own names, however, and their careers suffered as audiences struggled to keep up with musicians who changed jobs, and thus names. For example, one of the most popular acts in early radio was a singing duo of Billy Jones and Ernest Hare, first known as the Happiness Boys for the Happiness Candy Company, later known as the Interwoven Pair when they sang for the Interwoven Socks Company.11

With this brief background, let me now turn to the question of devising a program and of translating print practices to sound. Because advertisers and ad agencies were accustomed to thinking in print, radio did not immediately present itself as a medium for advertising. Radio in its infancy was not viewed as a primary medium for advertising but rather one that supplemented print advertising. Few advertising executives in this era could conceive of selling a product solely through sound, particularly since commercials as we now think of them scarcely existed. Because programs were produced by advertising agencies for single sponsors, in a sense the entire program was an advertisement.

In one of the earliest books on radio advertising, published in 1929, New York Times radio writer Orrin E. Dunlap delineated how radio music works compared to print advertising:

The headline of a printed advertisement is extremely important. It catches the eye. The headline of an ethereal [i.e., radio] advertisement must attract the ear. It is usually done by the opening announcement or in some case an orchestra plays an introductory musical selection before a word is spoken. It is often easier to lure the ear with a snappy musical selection than with words (Dunlap 86).

Dunlap seemed even more convinced about the function of music in radio advertising as he continued, for by the next page he opined confidently that “music is more captivating than words on the radio” (Dunlap 87). He offered several examples, including the Maxwell House Concert program which took as its theme song the “Old Colonel March,” and wrote that “the old southern colonel referred to is no other than the gentleman often pictured in the magazine advertisements, on billboards … holding up the empty cup as he remarks, ‘Good to the last drop’” (Dunlap 90).12 In this way, advertisers could remind listeners of their sponsored programs and reinforce the sales work done by their programs.

The trade press of the 1920s and 30s is full of stories about clever advertising executives determining what kind of program would sell a particular product, stories that are often told with attention-grabbing headlines such as “Broadcasting a Cemetery,” or “Putting a Cigar on the Air” (Wilson, Landers; see also Johnson). Part of the reason for this hubris was that in the early days of radio advertising, selling by radio was a haphazard affair. In the late 1920s, market research was rudimentary, often little more than anecdotal, so that concocting programs such as those touted in the above titles was essentially little more than a hit-or-miss proposition. In the case of the cigar campaign, advertising man Sherman G. Landers of the Aitken-Kynett Company of Philadelphia described his audience as men over 30, but that was all (Landers 5). Landers also proffered what at the time something of a demographic insight: “We … set out to design a program that would attract the type of man who had already become a cigar smoker or the married man with a family looking for relaxation in the form of entertainment” (Landers 6).

Given this crude grasp of the market, Landers and his company decided to stay away from the “craze” of dance orchestras, which they thought would attract too young an audience for their product. Instead, their “final decision was to recreate the black face days of yore in an old-fashioned minstrel show,” which they did with comics Percy Hemus and Al Bernard in the resulting Dutch Masters Minstrelsprogram. These two entertainers were not stars, Landers admitted, but figures who became “almost as well known as the ‘Happiness Boys.’”

In outlining the program, Landers said somewhat cryptically that “since radio entertainment appeals through the ear, it would be necessary to have an association of ideas to register” (Landers 6). Landers seems to mean that using known, or familiar-sounding, songs would be the best way to sell his product, hence the turn toward minstrel songs. This strategy of familiarity was common in this early phrase of American consumerism, essentially educating people about how to be consumers by using well-known sounds or images with which to sell new products.13

Unlike print advertising, where sales could be measured in magazines and newspapers sold, radio advertisers had little idea of how many people were listening, or the composition of the audience. No ratings system existed until Archibald Crossley began the Cooperative Analysis of Broadcasting in 1929; before then, advertisers and sponsors gauged the success of programs by the quality and volume of listener response, and thus often sponsored contests whose main purpose was to solicit listener feedback. Many sponsors in this era also offered samples in order to gather information about listeners.14

Without a clear idea of a program’s listenership, agencies and sponsors had difficulty formulating programs that would appeal to the listeners whom the advertisers hoped to attract. Additionally, advertisers had to find a way to select or fabricate a musical sound or program that would somehow resonate with—or create—perceptions of the product itself. J. Walter Thompson’s Gerard Chatfield wrote in the company’s News Letter in 1928 that some products simply suggest a kind of program, writing that “Aunt Jemima”—of pancake mix fame—“should croon folk songs of the South,” for example (Chatfield 1). NBC executive Frank A. Arnold wrote in 1931 that “a sparkling water, or a ginger ale, or a summer drink, chooses for its copy program, a type of music suggestive of and thoroughly in keeping with the product itself” (Arnold 55).

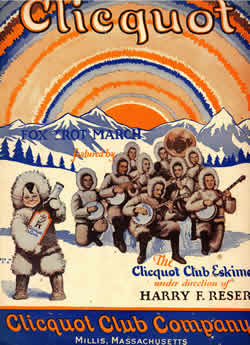

The Clicquot Club Eskimos

Arnold was probably thinking of the music for the Clicquot Club Eskimos program, a show sponsored by a ginger ale company whose product was sold by the Clicquot Club Eskimos, a band led by virtuoso banjo player Harry Reser.15 This program aired from 1923-6, originating in New York City on WEAF, NBC’s flagship station. Orrin E. Dunlap wrote in 1929 that “the Eskimos play ‘sparkling’ music because their ginger ale sparkles. They open their program with the Clicquot March and the bark of the Eskimo dogs. They hope that when listeners see the bottle with the Eskimo on the label they will recognize it as the same Clicquot that made the loudspeakers sparkle with pleasant banjo tunes” (Dunlap 88). No recordings of this program exist, but there is at least one script; below is a typical opening of their program that captures something of the flavor of the show.

Announcer: Look out for the falling snow, for it’s all mixed up with a lot of ginger, sparkle, and pep, barking dogs and jingling bells and there we have a crew of smiling Eskimos, none other than the Clicquot Club Eskimos tripping along to the tune of their own march—“Clicquot.”

Orchestra: (Plays “Clicquot”; the trademark overture.)

Announcer (Continuing): After the long breath-taking trip down from the North Pole, the Eskimos stop in front of a filling station for a little liquid refreshment—and what else would it be, but Clicquot Club Ginger Ale—the ginger ale that’s aged six months. Klee-ko is spelled C-L-I-C-Q-U-O-T. You’ll know it by the Eskimo on the bottle. (Slight pause.) Up in Eskimo-land where the cold wind has a whistle all its own and a banjo is an instrument of music, the Eskimos spell melody with a capital “M,” and tell us that “It Goes Like This.”

Orchestra: (Plays “It Goes Like This.”) (National Broadcasting Company, Making Pep and Sparkle Typify a Ginger Ale 7-8).

Note how the product advertisement is woven into the continuity (the connecting prose) of the program in this era of “indirect advertising.”

The Clicquot Club Eskimos program was so successful that NBC produced a lavish brochure in 1929 that touted the program to attract advertisers. Calling the Eskimos “among the most unique salesmen in the history of commerce,” the brochure set out to sketch the program’s attributes, including the theme song, a march composed by Reser mentioned by Dunlap called the “Clicquot Fox Trot March” (National Broadcasting Company, Making Pep and Sparkle Typify a Ginger Ale ii). The sheet music, published in 1926, featured Reser and the other members of the group (mostly banjo players) and the Clicquot mascot, a cherubic “Eskimo,” holding a bottle of ginger ale much too big for him.16 The music was given away to fans writing in to the program; NBC claimed in 1929 that 50,000 requests had been made (National Broadcasting Company, Making Pep and Sparkle Typify a Ginger Ale 17). The march was every bit as effervescent as its sponsor could have hoped for, with Reser emphasizing the sparkling ginger ale with staccato marks and directions in the music:17

Example 1. Harry Reser: “Clicquot Fox Trot March,” mm. 7-14.

NBC said that the Clicquot Club program was probably the first to use a “trademark overture,” that is, the “Clicquot Fox Trot March,” a piece of music that “is probably as well-known in introducing the Clicquot Club Company’s program as ‘Over There’ is in announcing a war picture.” Continuing:

The value of this from an advertising standpoint can hardly be overestimated. Millions of people from coast to coast are put into a receptive frame of mind to hear the Clicquot Club Eskimos’ program by the familiar jingle of sleigh-bells, the rhythmic crack of the whip and the bark of the huskies as they bring the Eskimos on to the radio stage for their weekly program. This musical preface and epilogue are “headline” and “signature” to the Clicquot Club Company’s air advertisement (National Broadcasting Company, Making Pep and Sparkle 5).18

Note here the use of language from print advertising used analogically. More interesting is the literalness driving such a conception of music; even though, as various advertising scholars have noted, tactics derived from psychological warfare employed in World War I found their way into advertising practices in the 1920s and after, the music used in the beginning of radio was not usually selected primarily for its affective qualities, but rather, its ability to reinforce imagery and text, to animate the product.19 Early radio advertising with music is a kind of a throwback to earlier advertising practices of selling the product based on its qualities, which are reinforced by sound, especially music, rather than attempting to use psychology to incite consumers to purchase.

This is interesting. Radio—sound—forced advertisers and advertising agencies to rethink their work, and they responded at first by simply adopting print to advertising with sound analogically. Only rarely, however, did they implement what was the newest in print advertising strategies, that is, ads that relied on psychology. Print ads employing tactics that implied that a woman was a poor mother if she didn’t use a particular product for her children, or created anxieties in consumers worried about bad breath (“halitosis” was a term resurrected from an old medical dictionary by advertisers for Listerine in the 1920s) were only infrequently echoed in early radio advertising.20 As Printer’s Inkwrote in 1930, “advertising helps to keep the masses dissatisfied with their mode of life, discontented with ugly things around them. Satisfied customers are not as profitable as discontented ones” (Dickinson 163, quoted in Ewen 39). What was new about radio advertising was sound, but by comparison to print ads it was conservative in approach.

Personality

Yet advertising with sound was used in one strikingly novel way. Sound could be used to make a program’s stars, and even products, come to life by emphasizing “personality.” Historian Warren I. Susman has written influentially about the 20th century move away from 19th century emphasis on “character” to “personality,” of self-sacrifice giving way to self-realization. Susman locates evidence for this change in the advice manuals published between 1900 and 1920. The key quotation that Susman finds in almost all these manuals is “ Personality is the quality of being Somebody” (Susman 277).

The impetus for developing one’s personality came, Susman says, from the problem of living in a crowd, a mass culture, in which distinguishing oneself from others was a prime concern.21 This new culture of mass consumption, mass production, mass media, and mass society began to emphasize not just personality, but the fascinating, stunning, attractive, magnetic, glowing, masterful, creative, dominant, forceful. Cultivating one’s personality was a way to stand out from the crowd, the mass, and this could be accomplished through consumption, purchasing goods that could be used to define oneself. Some of these goods and services were self-help books, elocution lessons, charm courses, and beauty aids—all designed to help consumers construct personalities, fashion selves.

Conceptions of “personality” were also shaped by the mass media. Susman does not examine radio, but his analysis of the role of film is striking. Until about 1910, he writes, the identities of film actors were concealed by the studios. But in 1910 the movie star was born, necessitating the use of the press agent and the skills of the advertising agency; the movie star was increasingly marketed as a personality. And so were music stars. David Suisman has written vividly of the marketing of Enrico Caruso by the Victor Talking Machine Company before the arrival of radio to mainstream audiences, and there were of course many recording artists from the popular realm who were well known through their recordings.

Radio advertisers clearly meant to capitalize on this new emphasis on personality, and, indeed, they helped drive it. Their discourses, and those of their performers, are replete with references to the importance of personality. As early as 1924, for example, S. L. Rothafel, known affectionately to early radio listeners as “Roxy,” said that:

I am convinced that the radio performer’s personality is more important than his voice, his subject or the occasion. Any of these may be poor or inopportune and still a speaker will succeed. But if his personality is flat, his purpose vague, he certainly will not command respect on the radio circuit (Young 246).22

William Benton, chairman of the board of Benton & Bowles, attributed the success of an “inexpensive little program” in 1935 featuring singer Lanny Ross by saying that they “built an atmosphere around him.” Ross’ program, The Log Cabin Inn (sponsored by Log Cabin syrup) was popular, according to Benton, because the audience liked Ross, followed his exploits, and rooted for him.

This whole factor of personalization, of sympathetic settings and background, of illusion—is, in our judgement, the most fascinating and important in any study of the future of radio: How to get more of it, how better to personalize the stars, how to put them in situations where the public is with them and wants them to succeed and your product along with them (Benton 10).

NBC’s used a standard form for auditioning new readers and musicians, and one of the criteria to be addressed by the auditioner was “Personality” (along with “Quality,” “Musicianship,” and others, found in the Archives of the National Broadcasting Company at the Wisconsin State Historical Society, Box 2, Folder 82).

What is interesting, however, is that advertising agencies extended the concept of personality to goods themselves. NBC’s brochure on the Clicquot Club Eskimos discussed the selection of music, which was designed to emphasize the “ginger, pep, sparkle, and snap” of the product: “Manifestly, peppy musical numbers of lively tempo were in order. The banjo, an instrument of brightness and animation, was deemed most suitable in typifying the snap of Clicquot Club personality” (National Broadcasting Company, Making Pep and Sparkle5).

More generally, William H. Ensign said in 1928 that “National Advertisers find that radio … carries their names or the names of their products into millions of homes in a way which is not only conducive to good will building—but which stamps those names with a personality that makes them mean more than just something to be bought,” as though consumers were not merely purchasing a product but personality itself (“Radio Rays,” J. Walter Thompson Company newsletter no. 1, January 1, 1928, 20-1, quoted by Cohen, Making a New Deal 139). The advertising literature of the day was filled with discussions of how to give a product personality. As early as 1929, an NBC promotional book on broadcast advertising said that advertisers and their agencies realized that they could devise programs to stimulate the listener’s imagination, “so that he cloaks an inanimate product in living personality” (National Broadcasting Company, Broadcast Advertising 31).

Inevitably, music frequently played a role in developing a product’s personality, and discussions of musical programs by broadcasters trumpeted this. NBC concluded in its brochure on the Clicquot Club Eskimosprogram that “even a ginger ale may be personalized and dramatized” (National Broadcasting Company, Making Pep and Sparkle 24). A different brochure produced by NBC about the Ipana Troubadours program claimed that the broadcast advertising of the toothpaste “has given personality to a Tooth Paste” (National Broadcasting Company, Improving the Smiles of a Nation!24; emphasis in original). Not coincidentally, both of these were popular programs with well-known musicians.

Which Music?

Advertisers learned that personality could be made vivid through music, and that musical programs were popular with audiences, so much so that sponsored musical programs quickly became common on the airwaves by the late 1920s and early 1930s. Advertisers discovered early on that musical programs could reliably attract audiences, and the catchphrase among advertisers was that music was radio’s “safety first” (see for example, Dunlap 73). Frank A. Arnold wrote that “in the early days of national broadcasting the thing which probably saved the day was the discovery that ‘the great common denominator of broadcasting’ was music” (Arnold 29), because the great variety of regions, languages, classes, etc. made it difficult to devise a program with mass appeal. For Arnold, it was music that had created the national audience for radio; regardless of language or country of origin, “every one in his group knew and appreciated the language of music” (Arnold 30). P. H. Pumphrey wrote in 1931 that “with rare exceptions, the largest and the surest audiences are built by musical programs” (Pumphrey, “Choosing the Program Idea” 40).

While peppy banjos might seem to be the right kind of music for the Clicquot Club ginger ale, most musical programs were not so easily conceived. Deciding what music should be featured on a sponsored program was normally the subject of a great deal of debate between the sponsor and its advertising agency, for there were competing ideas about which music was most appropriate: sponsors wanted music that they felt best projected the image they wanted for their product and addressed the market as they saw it, as in the case of the Dutch Masters Minstrels program. Advertising agencies frequently had differing thoughts about this, and then there was the thorny question of audiences and their musical preferences, which arose slightly later.

Despite these tensions, the early debates about which music was most suitable usually coalesced around the question of classical musicor jazz.23 Advertising agencies tended to prefer classical music because of the prestige and legitimacy it conferred on their young profession, an attitude aided by a potent public discourse about the power of radio to uplift the tastes of the nation.24 Sponsors, however, tended to advocate music that would enhance their product’s image, or sell it, and that was usually music more popular than classical music. And sometimes meddlesome sponsors wanted to choose the music themselves.25, the choice of music is really more likely to depend on the musical taste of the advertisers’ president, chairman of the board, sales manager, advertising manager, and others who make up the committee on strategy” (Pumphrey, “Choosing the Program Idea” 40). Alice Marquis writes that the music played by Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians was selected by the wife of the advertising manager for General Cigar Company (Marquis 392, citing Carroll ix).]

The debate about classical music versus jazz has been discussed by two major radio historians, Susan J. Douglas, and Michele Hilmes, but, not being musicologists (or musicians) they take these terms largely at face value. Both authors assume that “jazz” and “classical” mean much the same now as they did then. In fact, the terms as used by everyone involved in broadcasting were fairly close together in this period. “Jazz” referred not to a music with a high improvisational content performed mainly by African Americans, but, rather, highly arranged quasi-classical dance tunes performed by white musicians, many with classical musical training and backgrounds. Paul Whitemanis the best example of a “jazz” musician in this discourse, and indeed was the most prestigious and influential figure in this music in this era.

“Classical” in the late 1920s and 1930s in broadcasters’ discourse referred not to “classics,” but mainly light works, light classics, and a few warhorses. In his 1931 book on advertising, Frank A. Arnold provided a script for the General Electric Hour that aired on WEAF in New York City on November 8, 1930. This was an hour-long program that featured speeches by Floyd Gibbons, “famous journalist and adventurer,” and music performed by the General Electric Orchestra conducted by Walter Damrosch. The selections on that particular program included “Suite from ‘Henry VIII’ ” by Saint-Saens [sic]; “Second and Fourth Movements from ‘Symphony in G’” by Haydn; “Whispering of the Flowers” by von Bloom; and “Overture to ‘Rienzi’ ” by Wagner. In 1927, a nationwide poll of listeners resulted in a list of favorite compositions. Some are well known—Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, and Wagner’soverture to Tannhäuser heading the list—but over half were light classics, such as Rudolph Friml’s The Firefly, Victor Herbert’s “Dagger Dance” from Natoma, and Edwin Poldini’s “Poupee Valsante” (“Radio Listeners Vote for Favorite Composers,” 606).26 There were many such lists and surveys that contained a similar smattering of warhorses and many light works.

The archival records of the J. Walter Thompson company suggest that broadcasting of music was well underway before higher executives began to wonder about it. When they did finally begin to take it more seriously, the first issue they wanted addressed with respect to the use of music in advertising was this question concerning classical music or jazz. This matter was confronted by J. Walter Thompson executives in their staff meeting on April 3, 1929, at which point their broadcasting department had been active for over a year. According to Henry P. Joslyn, head of the radio department at the time, “the question as it came to me was the question of jazz and classical music as media for radio advertising.” Joslyn patiently explained to the gathered executives, still thinking in terms of print, that this was the wrong question; clients like different musics, as do audiences.

The subtext, though, concerned the “quality” of programming. Classical music, even in its lighter forms, was seen as more highbrow than jazz, and thus a more suitable music for advertising, at least in the ears of the J. Walter Thompson executives. But as one contemporary guidebook to radio advertising put it, advertising agencies needed to chart a path between “popularity” and “distinctiveness” (i.e., between lowbrow and highbrow) (Felix 134).27 Agencies and/or clients wanted to put “good” programming on the air—which for them usually meant classical music—but the listening public might want something else.

And the listening public might actually listen to music differently, further influencing the choice of music. A 1930 article by Jarvis Wren, Radio Advertising Specialist at Kenyon & Eckhardt in New York City, argued that many musical programs tended not to grab the undivided attention of the listener, at least if they featured unobjectionable music. In such cases, the sales message might be lost. This was a particular problem when the music was of a “dreamy type,” such as Hawai’ian guitars. Musical programs, however, could command a large audience. For Wren, musical programs were the most effective when the product was already well known, or when the sales message was simple and straightforward, or when the program was going to be supplemented by a good deal of print advertising. In other cases, such as a launching a new product, he believed the dramatic program to be superior (Wren 27).

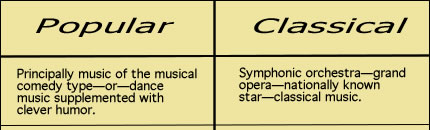

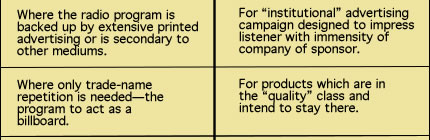

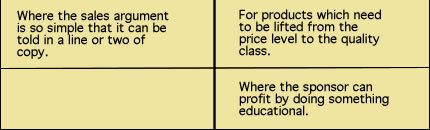

These ideas appeared in a more formulaic way in a 1931 publication, which included a table.

This table shows that questions of which music was the most appropriate went beyond the image—the personality—desired for a particular product, the sponsor’s preferences, or even the preferred audience, revealing a prejudice against the audiences for popular musics. From the highbrow perspective of advertising agencies and their clients, popular music audiences were thought to have short attention spans, necessitating reinforcement of the radio program by print advertising, and were thought to be unable to digest longer sales campaigns. Classical music audiences were assumed to be more intelligent, and broadcasting classical music could still generate goodwill in this select audience, grateful for classical music in an environment increasingly cluttered by various kinds of popular music.

The ideal, however, was a product that could appeal to large and diverse audiences while offending the fewest people. The Clicquot Club Eskimos was such a program. The company president’s idea was to place that program on as many affiliate stations as possible, a strategy summed up by NBC, which aired the program, as “ ‘tell it to the masses, and the classes will understand’ ” (National Broadcasting Company, Making Pep and Sparkle 6).

Audiences

Yet this was a fairly crude notion of what audiences might want, and by the end of the 1920s, polls and ratings came to dominate how advertisers and their agencies conceived programs. Early polls addressed the question of classical music or jazz, or musical preferences more generally. Radio writer Edgar H. Felix, for example, wrote in 1927 with palpable relief that

fully 70 per cent of the letters written to WEAF by admiring listeners in 1922 were in response to dance or jazz programs, 25 percent to classical programs, and 5 per cent to so-called educational features. A year later, jazz dropped to about 35 per cent of the response, classical music rose to 35 per cent, and educational talks . . . increased to 35 percent. These figures were brought forward as evidence that the radio audience had improved greatly in its tastes (Felix 123).

Felix accounted for the popularity of jazz by noting that many stations solicited requests, and that the “poor musical quality of reception then attainable simply exaggerated the more raucous element of jazz music” (Felix 123). Nationally, however, by the late 1920s, jazz or dance music was the most popular music on the air, although classical music never disappeared.

Data such as those employed by Felix were common. In addition to listener mail, there were countless polls about listener preferences, polls that advertisers and sponsors used to conceive programs.28 Depending on how the poll was worded and the kinds of musical categories employed, the poll results usually favored dance music, though classical music fared better in some polls. Taking polls and encouraging listener responses was the first step away from simple assertions of advertisers’ and sponsors’ musical tastes in programming. In a broadcasting environment in which advertising paid for programming, obtaining accurate information on listeners’ preferences was crucial, and polling and audience surveys quickly became prevalent and increasingly scientistic.29 These polls and listener surveys helped advertisers and advertising agencies tailor programs to fit the desired audience, based on the kind of music used.

Polling, and the idea of attempting to capture a particular audience for a particular product with particular music, ushered in the beginning of the end of the goodwill concept. Advertising agencies became bolder about incorporating advertising messages into the programs and targeting particular audiences, and less concerned with generating goodwill among audiences generally.

Programs

The Fleischmann Hour

One program that straddled the “classes and the masses” with great and long-lasting success was The Fleischmann Hour, starring crooner Rudy Vallée, and I will spend some time discussing this program as a way of pulling together the various strands of argument in this article.

On September 5, 1929, J. Walter Thompson began producing and airing a program sponsored by Standard Brands’ Fleischmann’s Yeast.30 Rudy Vallée was the main attraction. John Reber, by summer of 1929 the head of the Radio Department, told his colleagues at a staff meeting on August 26 that the audition of the program went well. An “audition” was a hearing, in Reber’s words, “merely a parading before you of the talent and of the general idea to be developed. We get it for nothing” (J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, Box 2, Folder 1). Auditions were probably put on for sponsors to see before their program aired. Reber reported that the star was “really marvelous.”

But Vallée did not get much of a spotlight at first. The early broadcasts featured Vallée mainly as a bandleader, not as a personality. The announcer, the renowned Graham McNamee, did virtually all of the talking except for Dr. R. E. Lee, head of the Fleischmann Health Research Department, who told the listeners of the health benefits of ingesting three Fleischmann’s Yeast Cakes per day. By the program that aired on January 14, 1932, the musical variety show format started to solidify, reducing the announcer to little more than a commercial spokesman for the yeast; in the past he had been the main speaker, as on most programs. But Valleé, who previously had only announced the numbers he was playing, began, at the behest of J. Walter Thompson, introducing the guests as well. “This kind of personality opportunity became a JWT program characteristic,” according to the brief, undated history of the program written by an anonymous employee of the company (“Fleischmann’s Yeast”). By the end of April 1932, Vallée told his listeners that he was both “announcing and directing” the Fleischmann Yeast Hour. Vallée says in his second autobiography that the show by 1932 became “a program that was to discover and develop more personalities and stars than any radio show before or since” (Vallée 87). [Listen to excerpt from The Fleischmann Hour]

Turning Vallée into the de facto master of ceremonies, the chief personality, was something of an accident. At one point in 1932, J. Walter Thompson was faced with a dilemma: one of the sketches on the program, the comedy team Olsen and Johnson, was popular with audiences, judging by the ratings, but not with the sponsor. Executives at the agency felt that the larger problem, putting acts on Vallée’s program that the public or sponsor might not like, could be circumvented by implying in the script that the immensely popular Vallée had chosen these acts himself, “so that all who like Vallee will like the show because Vallee made it up,” according to John Reber (J. Walter Thompson, Creative Staff Meeting, December 21, 1932, Box 5). “But the facts are,” said Reber, “that Vallee doesn’t know now what is going to be rehearsed this afternoon. He doesn’t write one word of the script. All of the things about how he first met these people, etc., we make up for him” (J. Walter Thompson, Creative Staff Meeting, December 21, 1932).31 This solution effectively created an illusion whereby one personality anointed others with this same quality as he directed the program. For my purposes, the main interest of this story concerns how ratings revealed audience

preferences that could be used to manipulate sponsors.

The Fleischmann Hour was innovative and exemplary in many ways. In a 1931 speech before the League of Advertising Women at the Advertising Club in New York City, Daniel P. Woolley, vice president of Standard Brands, discussed his notion of “tempo,” that is, matching a product to a particular kind of program and entertainment, in the period before advertisers had much concrete knowledge of their audiences.32 His main example was the The Fleischmann Hour. In those days, yeast was sold not simply for baking bread, but for health, as a kind of vitamin, as we have seen. So Fleischmann’s Yeast was marketed as more of a medicine than a foodstuff in this era. A hard sell, since it tasted bad. Woolley’s own words are worth quoting at length:

Yeast for health is a very delicate subject to handle. It has much to do with good health, so when we started to look around for a radio program we said, “What is the audience we have to deal with?”

We decided that, probably, now-a-days they wanted “It” more than anything else. Who had “It” the most of anybody we could find? We found a young crooner, Rudy Vallee, and we found the young ladies panting over him and even some of the old ladies. He also has a great many men admirers. So we engaged Rudy Vallee as the star of this great thing called Health. We wanted him to croon but also we wanted more in the program. We wanted athletics or robust health to play a part. We went through the list—Jack Dempsey and all. Finally we said, “Graham MacNamee [sic] as the noted sports announcer stands for sports!” (“Reproduce Product’s Tempo in Program,” 26).

“It” refers to sex appeal, the pronoun having been made famous by its attachment to movie star Clara Bow, the “It” girl.33

Woolley said that they wanted to make sure they had a well-rounded program, and so they should get some “ladies with deep and soulful voices and a soloist.” They also included Dr. Lee on the program to talk about health issues. “Now, I might tell you that that combination of MacNamee [sic] for virility, and Vallee for crooning, Dr. Lee to give the advice of the old family physician, plus a lady who sings, has been a very successful radio program” (“Reproduce Product’s Tempo,” 26). It should be noted here that crooning was widely hailed as an effeminate mode of singing, and so balancing Vallée with McNamee was an important consideration for Standard Brands.34

Woolley was right. Vallée had It—sex appeal and that all-important quality, personality. He was hugely popular, the first musical superstar in the new medium of radio, and was widely written about.35 The Fleischmann Hour remained on the air for over a decade, though as the practice of eating yeast for health waned the program was rechristened The Royal Gelatin Hour in 1936. (Royal Gelatin was also owned by Standard Brands, so the sponsor did not change.)

Aunt Jemima

To contrast Vallée’s hugely popular and innovative variety program, it is useful to examine an earlier program, the Aunt Jemima program also produced by the J. Walter Thompson Company. This program only preceded Vallée’s by a year, but speaks to the issue of how radio producers in advertising agencies were piggybacking radio onto earlier forms of entertainment that were known to be popular, namely, minstrelsy, as in the case of the Dutch Masters Minstrels program above.

Yet J. Walter Thompson’s executives thought such a program perfectly natural for selling pancake mix, as noted above. This supposed naturalness, however, still had to be framed and introduced to everyone associated with the product. Perceptions of the quality of sponsored programs occupied many of the J. Walter Thompson staff meeting minutes. Henry P. Joslyn described one of J. Walter Thompson’s own ads, for Aunt Jemima’s Pancake Flour in the meeting on April 3, 1929, an ad that:

… advertised by a troop of darkies who sing and play for the white folks at Col. Higbee’s plantation. They are real Negroes, headed by J. Rosamond Johnson and Taylor Gordon who have toured Europe and America as concert singers. They are famous under their own names but go on the air as Uncle Ned and Little Bill. Aunt Jemima herself is one of the characters in the troop and a small orchestra, quartette and chorus is built around them. The dialogue brings the name “Aunt Jemima” to the listening ear between each number. The “act” is one of the best on the air today. Occasional jazz is used. Spirituals and old-time favorites are more frequent (J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, Box 1, Folder 7).36

Unmentioned by Joslyn, the title character was played by vaudevillian Tess Gardella. As one might guess from the foregoing, the scripts for these early shows were written entirely in dialogue. Musical selections were sometimes named, sometimes not. Occasionally the script directions would simply say “Quartette—Lively Spiritual” or “Lively instrumental,” and referred to Aunt Jemima and her friends as either docile or lively.

J. Walter Thompson Company staff nonetheless found the program effective. The company News Letter from December 15, 1928 includes a report from the company’s Chicago office.

“We settled ourselves in our leather chairs, expectantly, and out of the loud speaker came softly the distant sound of Negro field hands, singing an old southern song,” writes Paul Harper of the Chicago office.“With this pleasing background the announcer told us we were to be transported to Aunt Jemima’s cabin down on the levee, where we would be given a glimpse of a Negro frolic. Then one character after another was introduced and a sprightly and amusing dialogue followed. Aunt Jemima called on various individuals to perform their musical specialties. One after the other, the members of the company sang negro spirituals, played on accordion and banjo, joked with each other and told anecdotes, punctuated with uproarious and infectious laughter.

“The Aunt Jemima selling talk was worked in very unobtrusively and naturally. The whole entertainment hung together beautifully and did not drag for a single moment. It was apparent to every one present that the whole thing was a very distinctive piece of work and far above the average of radio programs” (“Aunt Jemima on the Radio”).

Joslyn emphasized the importance to preparing the sales organization and salesman before the commercial is ever aired. With respect to Aunt Jemima, “the trade and the salesman out in the field all of the sudden heard a lot of rather native stuff on the air, tied up to Aunt Jemima. They didn’t understand it. They heard the old-time darkies and they heard a lot of murmuring and whispering during the act—things are not always distinct. It is very realistic and very good. You are not supposed to hear everything. But it was not ‘sold’ to them and then wrote in and said they couldn’t understand it. …” (J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, Box 1, Folder 7). Nevertheless, Aunt Jemima sales figures climbed steadily after the introduction of the radio program. In a staff meeting on April 16, 1930, John Reber presented his colleagues with the following figures: sales for 1928 were up 14 percent over the previous year; 1929, up 30 percent; 1930, 35 percent in January (J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, Box 2, Folder 3).

The transition of advertising from print to sound in the 1920s demonstrates how a new technology does not simply burst on the scene and changes everything. Instead, new technologies such as radio are at first viewed through the lens of existing needs and practices, and only gradually come to shape those existing needs and practices. Radio, bought and paid for by advertisers, was the culminating force in the wave of consumerism that had begun at the end of the 19th century. Programs such as the Fleischmann Hour and superstars such as Rudy Vallée transformed advertising from a relatively straightforward process of hawking goods to a mechanism of funding programs, and imbuing those programs with the ideologies of modern consumerism. The Fleischmann Hour and other programs were educating people about their roles as consumers in an era widely viewed as a kind of technological modernity, encouraging people to fashion selves not through their experience in their communities, in churches, in schools, in unions, but through mass-marketed goods made real and vivid—and desirable—on the radio.

Works Cited

Discography

Reser, Harry. Banjo Crackerjax, 1922-1930. Yazoo 1048, 1992.

Musical Scores

Reser, Harry. “Clicquot Fox Trot March.” New York: Harry Reser, 1926.

Unpublished Materials

Suisman, David. “The Sound of Money: Music, Machines, and Markets, 1890-1925.” Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 2002.

Archival Materials

Benton, William B. “Building a Program to Get an Audience.” Address before the annual meeting of the Association of National Advertisers, Inc., White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, May 6-8, 1935. Library of American Broadcasting, University of Maryland, Hedges Collection, 22, Advertising Agencies’ Part in Broadcasting’s Growth (A-Q), Box 4, File 6.

Chatfield, Gerard. “Advertising Agency Should Recognize and Use Radio.” J. Walter Thompson Company, News Letter, vol. 10 no. 8, September 15, 1928. J. Walter Thompson collection, John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University. Newsletter Collection, Main Newsletter, Box A.

“Fleischmann’s Yeast – Rudy Vallee.” J. Walter Thompson Archive at the John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University, JWT Account Files, Box 17.

J Walter Thompson Company. “Aunt Jemima on the Radio.” News Letter, vol. 10, no. 25, December 15, 1928. Contained in the J. Walter Thompson collection, John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University, Newsletter Collection, Main Newsletter, Box A. J. Walter Thompson Company.

“Radio Rays.” J. Walter Thompson Company, News Letter. no. 1, January 1, 1928.

J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, July 11, 1928, Box 1, Folder 5. John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University.

J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, April 3, 1929, Box 1, Folder 7. John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University.

J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, April 16, 1930, Box 2, Folder 3. John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University.

J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, August 26, 1929, Box 2, Folder 1. John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University.

NBC audition form. Archives of the National Broadcasting Company, Wisconsin State Historical Society, Box 2, Folder 82.

Vallée, Rudy. “Talk Given by Rudy Vallee in the Assembly Hall of the J. Walter Thompson Company, on the Evening of March 31, 1930.” J. Walter Thompson collection, John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University. J. Walter Thompson Company Staff Meeting Minutes, Box 8, Folder 2.

Books and Articles

Adorno, Theodor. “Analytical Study of the NBC Music Appreciation Hour.” Musical Quarterly 78 (Summer 1994): 325-77.

Ames, Allan P. “In Defense of Mr. Hill.” Printer’s Ink February 1, 1934: 53-56. “Are You a ‘Middlebrow’?” Popular Radio June 1923: 619.

Arnold, Frank A. Broadcast Advertising: The Fourth Dimension. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1931.

Barnouw, Erik. The Sponsor: Notes on a Modern Potentate. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

“Branded Men and Women; Pioneers Who Paved the Way and Paid with Personal Oblivion.” Radio Guide March 3, 1932, 1.

Carroll, Carroll. None of Your Business: Or My Life with J. Walter Thompson (Confessions of a Radio Writer). New York: Cowles Book Company, 1970.

Cohen, Lizabeth. A Consumer’s Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. New York: Knopf, 2003.

———. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990. Cross, Gary. An All-Consuming Century: Why Commercialism Won in Modern America. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

Damrosch, Walter. “Music and the Radio.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 177 (January 1935): 91-93.

De Forest, Lee. “Opera Audiences of To-Morrow.” Radio World August 5, 1922, 13.

Dickinson, Roy. “Freshen Up Your Product.” Printer’s Ink February 6, 1930, 163.

Douglas, Susan J. Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination … from Amos ‘n’ Andy and Edward R. Murrow to Wolfman Jack and Howard Stern. New York: Times Books, 1999.

Dunlap, Orrin E., Jr. Advertising by Radio. New York: Ronald Press, 1929.

Dyer, Gillian. Advertising as Communication. New York: Methuen, 1982.

Dykema, Peter W., and Karl W. Gehrkens. The Teaching and Administration of High School Music. Boston: C. C. Birchard, 1941.

Ewen, Stuart. Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of the Consumer Culture. New York: McGraw Hill, 1976.

“Favorite Musical Numbers of the Farm Audience.” Broadcast AdvertisingJune 1929: 25-27.

Felix, Edgar H. Using Radio in Sales Promotion: A Book for Advertisers, Station Managers and Broadcasting Artists. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1927.

Finney, Frank. “Grand Opera, Symphonies and Cigarettes.” Printer’s InkJanuary 25, 1934: 13-16.

Freund, John C. Excerpts from an address broadcasted from WJZ. Wireless Age May 1922: 36.

Gellhorn, Martha. “Rudy Vallée: God’s Gift to Us Girls.” New Republic August 7, 1929: 310-11.

Grundy, Pamela. “ ‘We Always Tried to Be Good People’: Respectability, Crazy Water Crystals, and Hillbilly Music on the Air, 1933-1935.” Journal of American History 81 (March 1995): 1591-1620.

Hammond, Affie. “Listeners’ Survey of Radio.” Radio News December 1932: 331.

Hanson, Howard. “Music Everywhere: What the Radio Is Doing for Musical America.” Etude 53: 84.

Hess, Herbert W. “History and Present Status of the ‘Truth-in-advertising’ Movement as Carried on by the Vigilance Committee of the Associated Advertising Clubs of the World.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 101 (May 1922): 211-220.

Hettinger, Herman S. A Decade of Radio Advertising. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1933.

Hilmes, Michele. Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922-1952. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Johnson, Hal. “We Made the Program Fit the Product.” Broadcast AdvertisingMarch 1930: 6-8.

Jordan, Mary. “Radio Has Made ‘High-Brow’ Music Popular.” Radio NewsFebruary 1928: 884.

Kempf, Paul. “What Radio Is Doing to Our Music.” Musician June 1929: 17.

Landers, Sherman G. “Putting a Cigar on the Air.” Broadcast AdvertisingJune 1929: 5.

Lears, Jackson. Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America. New York: Basic, 1994.

Lears, T. J. Jackson. “From Salvation to Self-Realization: Advertising and the Therapeutic Roots of the Consumer Culture, 1880-1930.” The Culture of Consumption: Critical Essays in American History, 1880-1980. Eds. Richard Wightman Fox and T. J. Jackson Lears. New York: Pantheon, 1982. 3-38.

Leiss, William, Stephen Kline, and Sut Jhally. Social Communication in Advertising: Persons, Products, and Images of Well-being. 2d ed. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Lynd, Robert S., and Helen Merrell Lynd. Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1929.

Lyon, Leverett S. “Advertising.” The Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, vol. 1 (1922). Marchand, Roland. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920-1940. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Marquis, Alice Goldfarb. “Written on the Wind: The Impact of Radio during the 1930s.” Journal of Contemporary History 19 (1984): 385-415.

McLaren, Carrie, and Rick Prelinger. “Salesnoise: The Convergence of Music and Advertising.” Stay Free!, http://www.stayfreemagazine.org/archives/15/timeline.html, 1998.

McCracken, Allison. “ ‘God’s Gift to Us Girls’: Crooning, Gender, and the Re-Creation of American Popular Song, 1928-1933.” American Music 17 (winter 1999): 365-95.

McDonald, E. F. “What We Think the Public Wants.” Radio Broadcast March 1924: 382-84.

McGovern, Charles. “Consumption and Citizenship in the United States, 1900-1940.” Getting and Spending: European and American Consumer Society in the Twentieth Century. Eds. Susan Strasser, Charles McGovern, and Matthias Judt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 37-58.

“Mr. Average Fan Confesses that He Is a ‘Low Brow.’ ” Radio RevueDecember 1929: 30-32.

“Mr. Fussy Fan Admits that He Is a ‘High-Brow.’ ” Radio Revue January 1930: 16.

Murphy, William D. “High Hats for Low Brows.” Printer’s Ink February 8, 1934: 61-62.

“Musical Contest Program Sells 27 Tons of Candy in Five Weeks.” Broadcast Advertising October 1930, 12.

National Broadcasting Company. Broadcast Advertising: A Study of the Radio Medium—the Fourth Dimension of Advertising. Vol. 1. New York: National Broadcasting Company, 1929.

National Broadcasting Company. Broadcast Advertising. Vol. 2, Merchandising. New York: National Broadcasting Company, 1930.

National Broadcasting Company. Broadcast Merchandising. New York: National Broadcasting Company, n.d.

National Broadcasting Company. Improving the Smiles of a Nation! How Broadcast Advertising Has Worked of the Makers of Ipana Tooth Paste. New York: National Broadcasting Company, 1928. Library of American Broadcasting, University of Maryland, Pamphlet PAM 1519.

National Broadcasting Company. Making Pep and Sparkle Typify a Ginger Ale. New York: National Broadcasting Company, 1929. Library of American Broadcasting, University of Maryland, pamphlet 1546.

National Broadcasting Company. Musical Leadership Maintained by NBC. New York: National Broadcasting Company, 1938.

Olney, Martha L. Buy Now, Pay Later: Advertising, Credit, and Consumer Durables in the 1920s. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Orchard, Charles, Jr. “Is Radio Making America Musical?” Radio BroadcastOctober 1924: 454.

Palmer, James L. “Radio Advertising.” Journal of Business of the University of Chicago 1 (October 1928): 495-96.

Pumphrey, P. H. “Choosing the Program Idea.” Broadcast Advertising July 1931: 15.

———. “Writing, Casting and Producing the Radio Program.” Broadcast Advertising August 1931: 17.

“Radio Cultivates Taste for Better Music.” Radio World July 19, 1924: 24.

“Radio Fan Goes to See Opera after Broadcast.” Radio World April 14, 1923: 29.

“Radio Listeners Vote for Favorite Composers.” Radio News December 1927: 606.

“Radio’s Magic Carpet; Extensive Printed Advertising Reenforces Broadcast Campaign.” Broadcast Advertising July 1929: 5.

“Replies to WJZ Questionnaire on Listeners’ Tastes Show Classical Music More Popular than Jazz.” New York Times February 21, 1926: sec. 8, p. 17.

“Reproduce Product’s Tempo in Program, Says Woolley.” Broadcast Advertising May 1931: 26.

Rubin, Joan Shelley. The Making of Middlebrow Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

“Senator Borah on Marketing” (editorial). Printer’s Ink August 2, 1923: 152.

Simon, Robert A. “Giving Music the Air.” Bookman 64 (1926): 596-99.

Smulyan, Susan. “Branded Performers: Radio’s Early Stars.” Timeline 3 (1986-7): 32-41.

———. Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting 1920-1934. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

Stamps, Charles Henry. The Concept of the Mass Audience in American Broadcasting: An Historical-Descriptive Study. 1957. Reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1979.

Susman, Warren I. Culture as History: The Transformation of American Society in the Twentieth Century. New York: Pantheon, 1984.

Taylor, Timothy D. “Music and the Rise of Radio in Twenties America: Technological Imperialism, Socialization, and the Transformation of Intimacy.” Historical Journal of Film, Television and Radio 22 (2002): 425-43.

Tremaine, C. M. “Radio, the Musical Educator.” Wireless Age September 1923: 39-40.

Vallée, Rudy, with Gil McKean. My Time Is Your Time: The Rudy Vallée Story. New York: Ivan Obolensky, 1962.

Wakeman, Frederic E. The Hucksters. New York: Rinehart, 1946.

Wallace, John. “The Listeners’ Point of View.” Radio Broadcast April 1926: 667. Ware, Norman J. Labor in Modern Industrial Society. Boston: D. C. Heath, 1935.

“What the Public Likes in Broadcasting Programs Partly Shown by Letters.” Radio World July 21: 1923.

Williams, Russell Byron. “This Product Takes That Program.” Broadcast Advertising May 1931: 10.

Wilson, Allan M. “Broadcasting a Cemetery.” Broadcast AdvertisingSeptember 1929: 3.

Wren, Jarvis. “The Musical vs. Dramatic Radio Program.” Advertising and Selling August 6, 1930: 27.

Young, James C. “Broadcasting Personality.” Radio Broadcast July 1924: 246-50.

-

Thanks are due to the good people at the John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University, especially Jacqueline Reid and Ellen Gartrell; Michael Henry at the Library of American Broadcasting at the University of Maryland; and Sherry B. Ortner, as always. I would also like to thank the audience at the University of California, Los Angeles, who heard this paper no March 11, 2003, for questions and comments that helped improve this paper. All images are from the Library of American Broadcasting at the University of Maryland, except where noted. ↩ - For a treatment of this earlier period, see Taylor. ↩

-

See Olney. ↩ - For more on consumption in this era, see Ewen and McGovern. ↩

- For a discussion of the efforts to inform the public about radio, see Taylor. ↩

- Hill was the model for the authoritarian and intimidating Evan Llewellyn Evans in Frederic E. Wakeman’s bestselling novel on the advertising industry. ↩

- Merchandising was an important consideration for sponsors; in 1929, NBC produced a booklet for potential advertisers. The first volume was all about broadcasting and programs. In 1930, a second volume appeared: Broadcast Advertising, vol. 2, Merchandising. This booklet contained many more merchandising ideas than NBC promoted in their Ipana Troubadours pamphlet, including program theme song sheet music, a personal budget book, pamphlets about programs, and more. ↩

- See, for example, National Broadcasting Company, Musical Leadership Maintained by NBC. ↩

- See Smulyan, Selling Radio. Frank A. Arnold attributes Damrosch as saying that radio has done more to educate people “to an appreciation of good music in the last five years than all other methods used in the preceding twenty-five years” (Arnold, Broadcast Advertising 32). This was a familiar refrain in the early days of radio: that it could uplift the tastes of the nation. See Damrosch. For a study of Damrosch’s program, see Adorno. ↩

-

Most of the music played was the familiar panoply of light classics, though the program’s theme was entitled “The Call of the Desert” (composed, I believe, by Howard Coates). ↩ - See “Branded Men and Women,” and Smulyan, “Branded Performers.” ↩

-

It is not entirely clear which Maxwell House program Dunlap is referring to, for there were several in the late 1920s. ↩ - See Leiss, Kline, and Jhally for a discussion of this idea. ↩

- Some companies gave away massive amounts of free products. The George Ziegler Company gave away 27 tons of candy in five weeks in 1930, for example (see “Musical Contest Program Sells 27 Tons of Candy in Five Weeks”). ↩

- Reser (1896-1965) was a spectacular banjo virtuoso. For a compilation album, see Banjo Crackerjax, 1922-1930. ↩

-

The last page of the sheet music of Reser’s “Clicquot Fox Trot March” is an advertisement for Paramount banjos and lists the instrumentation of the group: Paramount tenor banjo; two Paramount plectrum banjos; Paramount melody banjo; Paramount B-flat melody banjo saxophone, piano, tuba, drums, Paramount tenor harps. ↩ -

This excerpt omits a 6-bar introduction. ↩ -

The sleigh bells and barking dogs are not represented in the published version of the Clicquot Club March, excerpted in Example 1. As far as I know, no recordings of this program exists, though the program reappeared on radio in 1950. A recording of one of those broadcasts has been privately issued. ↩ - For more on the rise of psychological techniques used in advertising in this period, see Dyer, Lears, “From Salvation to Self-Realization,” and Leiss et al. ↩

- For a discussion of Listerine and the question of halitosis, see Marchand. In Middletown, Robert S. Lynd and Helen Merrill Lynd write that advertising was “concentrating increasingly upon a type of copy aiming to make the reader emotionally uneasy, to bludgeon him with the fact that decent people don’t live the way he does: decent people ride on balloon tires, have a second bathroom, and so on. This copy points an accusing finger at the stenographer as she reads her motion picture magazine and makes her acutely conscious of her unpolished finger nails, or of the worn place in the living room rug, and sends the housewife peering anxiously into the mirror to see if her wrinkles look like those that made Mrs. X— in the ad ‘old at thirty-five’ because she did not have a Leisure Hour electric washer” (Lynd and Lynd 82, footnote 18; emphases in original). ↩

- See Taylor for a discussion of the crowd and radio. ↩

- Rothafel’s program was Roxy and His Gang, one of the earliest hit radio programs, a musical variety show broadcast from 1927-1931. Later he became known as the guiding hand behind the building of Radio City Music Hall. ↩

-

The question of what kind of music was most suitable for advertising was mainly of concern to the major advertising agencies and national brands. Small, rural radio stations would broadcast almost anything that happened to come through its doors. See Grundy. ↩ - For more on the legitimation of advertising, see Marchand. On the question of uplifting the taste of the nation, it is interesting to note that landmark classical broadcasts were repeatedly reported as news and editorialized about in the New York Times and other papers. And there were many published arguments about radio uplifting tastes. For just a few, see Freund, de Forest, “Radio Fan,” Tremaine, “Radio Cultivates Taste for Better Music,” Orchard, Wallace, Jordan, Kempf, Damrosch, Hanson, and the chapter “Radio as a Potential Force in Music Education” in Dykema and Gehrkens. For a thoughtful, less boosterish consideration of the subject, see Simon. For interesting discussions of a “lowbrow” product attempting to sponsor “highbrow” music, see Finney, Ames, and Murphy. For a scholarly treatment of the larger notion of taste and civilization in the face of mass culture, see Susman, Ch. 7. ↩

- P. H. Pumphrey writes that “in the current state of collected data on this subject [of type of music used in programs ↩

- The complete list, in order of popularity, is: Richard Wagner: Overture to Tannhäuser, Franz von Suppe: Poet and Peasant Overture, Franz Schubert: Marche Militaire, Ludwig van Beethoven: Fifth Symphony, Franz Schubert: Unfinished Symphony, Charles Gounod: Ballet Music from Faust, Jules Massenet: Meditation from Thais, Fritz Kreisler: Liedesfreud, Sir Arthur Sullivan: H.M.S. Pinafore, Peter Tschaikowsky: Nutcracker Suite, Rudoph Friml: The Firefly, Peter Tschaikowsky: Symphonie Pathetique, Victor Herbert: “Dagger Dance” from Natoma, Edvard Grieg: In the Morning, Carl Maria von Weber: Invitation to the Dance, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Overture to the Marriage of Figaro, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakow: Scheherazade, Edwin Poldini: Poupee Valsante. ↩

- There was a public discussion of how radio was changing tastes, with the terms “highbrow,” “lowbrow,” and even “middlebrow” being bandied about with some frequency. See “Are You a ‘Middlebrow’?,” Jordan, “Mr. Average Fan Confesses that He Is a ‘Low Brow,’ ” “Mr. Fussy Fan Admits that He Is a ‘High-Brow,’ ” and Murphy. ↩

-

See “What the Public Likes in Broadcasting Programs Partly Shown by Letters,” Palmer, McDonald, “Replies to WJZ Questionnaire on Listeners’ Tastes Show Classical Music More Popular than Jazz,” and Hettinger. See also Hammond and “Favorite Musical Numbers of the Farm Audience.” ↩ - See Douglas’ chapter “The Invention of the Audience” in Listening In; and Stamps. ↩

- Vallée’s autobiography says that the first air date was October 29, 1929 (Vallée 86). ↩

- See also Marchand, 49, for a discussion of this deception. Vallée writes in his second autobiography, however, that he was permitted to come up with his own list of guests, some known luminaries, and “many others whom I dug up or came across in my travels” (Vallée 88). ↩

-

See Marchand for a discussion of “tempo” in this period. ↩ - Thanks are due to Tara Browner for telling me of this. ↩

- On crooning as effeminate, see McCracken. ↩

- Most of the writing about Vallée was the stuff of fanzines, but see Gellhorn. Despite the huge amount of ink used about Vallée at the height of his popularity, there is only one scholarly work on him, McCracken. ↩

- J. Rosamond Johnson (1873-1954) was the brother of James Weldon Johnson and who had a distinguished career as a composer and performer. I have been unable to ascertain any information on Taylor Gordon. ↩