One of the most frustrating aspects of film music scholarship is the surprising difficulty one faces in finding literature on the subject. Although there are useful and worthwhile writings out there, everything seems either out of print, outrageously expensive, or scattered among tiny journals. Part of the problem is the interdisciplinary nature of film music studies; a mainstream musicology journal is loath to print an article using jargon from another field, especially if the music is widely thought to be prima facie of a subservient nature, and therefore second rate. Within film studies, the same situation applies; the majority of their readership is unfamiliar with the vocabulary of musicology, or even (especially) the ability to read music. This has led to a situation in which scholars, like savvy antiquers, have been reduced to scouring used bookshops or circulating tenth-generation illegal photocopies amongst themselves like black-market scavengers. With copies of Claudia Gorbman’s essential and long out-of-print Unheard Melodies (1987) going for up to one hundred dollars in paperback at bookstores, this underground network of Xeroxed distribution makes those interested in writing or reading about film music a very small club.

surprising difficulty one faces in finding literature on the subject. Although there are useful and worthwhile writings out there, everything seems either out of print, outrageously expensive, or scattered among tiny journals. Part of the problem is the interdisciplinary nature of film music studies; a mainstream musicology journal is loath to print an article using jargon from another field, especially if the music is widely thought to be prima facie of a subservient nature, and therefore second rate. Within film studies, the same situation applies; the majority of their readership is unfamiliar with the vocabulary of musicology, or even (especially) the ability to read music. This has led to a situation in which scholars, like savvy antiquers, have been reduced to scouring used bookshops or circulating tenth-generation illegal photocopies amongst themselves like black-market scavengers. With copies of Claudia Gorbman’s essential and long out-of-print Unheard Melodies (1987) going for up to one hundred dollars in paperback at bookstores, this underground network of Xeroxed distribution makes those interested in writing or reading about film music a very small club.

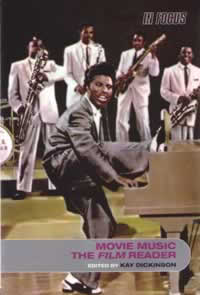

Kay Dickinson’s new book Movie Music: The Film Reader is the first anthology that attempts to compile many of the most important out-of-print and hard to find essays—these are the ones that have been most frequently cited and have influenced film music scholars for at least the last 15 years. Dickinson is well qualified to edit this collection; she is a lecturer in Film Studies at Middlesex University, London, but is equally acquainted with the methods and language of musicology, having also written and published a great deal on popular music, especially as it has related to technological innovation.

This perspective has led her to arrange the collection into four parts, with each part containing three or four essays: first, “The Meaning of the Film Score” summarizes different perspectives concerning a theoretical grounding for the role of music in film. Part Two discusses the role of “the song” in film both commercially and aesthetically. The third section engages with the political implications of music on film, and the final section collects three essays concerned with the visual representation of musicians in film. All of the essays are worthy of reprinting, and each contributes something new and important to the subject of film music.

In her introduction, Dickinson outlines more specifically the theoretical and methodological orientation of her selections. She attempts not only to make available hard-to-get important articles, but also to redress what she sees as an imbalance in the emphasis within the field on orchestral scores to the exclusion of popular music in film. Her introduction contains an excellent brief history of film music combined with an account of how scholars have tended to discuss that history. It is a nice way to include a mention of some of those writers whose work couldn’t find a place in this collection for various reasons. Among these, Michel Chion’s groundbreaking work on film sound, Anahid Kassabian’s more culturally inclusive writings, and Daniel Goldmark’s recent monumental project concerning Warner Brothers cartoons are particularly missed (see bibliography).

This is a thin book, coming in at just around 200 pages, and part of the limitations Dickinson must have faced is evident in the editing of many of the essays; she has been forced to cut most of them down from their original size. I initially thought this might be a problem, but skillful editing has meant a focusing of each essay’s message effectively. The first section is undoubtedly the most problematic, another indication of space limitations. In just four essays she attempts to cover both the theoretical writings on film as well as the range of work on orchestral scoring. All her choices were essential but each complicates rather than explicates the goal to map out a method for analysis of the orchestral score. The first essay, Kathryn Kalinak’s “The Language of Music: A Brief Analysis of Vertigo,” is the best chapter of her essential book Settling the Score, but is hardly about the theory of film music. Rather, it is an excellent summary of musical language for non-musicians, defining common terms like “interval,” “tempo,” and “pianissimo” within a casual discussion of Herrmann’s Vertigo score. For example, Kalinak uses the following figure to explain interval and the “dis-ease” of seventh chords, as well as harmony more generally (16):

Only two paragraphs deal with the interaction of music and image.

Reprinting Theodore Adorno and Hans Eisler’s “Introduction” and “Prejudices and Bad Habits” from their influential Composing for the Films was also essential as a historical document, but given such a prominent location could lead one to believe their writing is still as relevant as it once was. The conventions they are upset by—the leitmotiv, stock music, the geographical illustration—have all long ceased to be the main elements of film music’s composition. This problem is slightly heightened by the lack of publication dates for any of the articles. It would have been nice to have been given this date next to the article title, since even in the acknowledgments the only date given for this particular article is a recent 1994 reprint.

Claudia Gorbman’s essay “Why Music? The Sound Film and Its Spectator” from Unheard Melodies is one of those essays that is quoted everywhere and has rightly attained a position of authority, but here as the sole contemporary example of theorizing orchestral film music it comes across as being slightly eccentric. Gorbman’s theory is that much (orchestral) film music acts like easy listening music to smooth over the artificiality and “constructedness” of film, covering the seams as it were. Here Dickinson faced a problem. She had to include Gorbman’s influential essay; as I mentioned above, it is one of the most quoted and hard-to-find essays in the field. At the same time, the theories it expounds have been accepted as near-universal by scholars since then, who have come to understand “the orchestral score” as always working in this way. As there has been nothing to supercede it in the literature, orchestral music has hence been a problematic subject for those interested in writing about it. They must, by necessity, engage with Gorbman’s essay, but feel limited by its authority as well. How one would discuss, say, a jarring orchestral score by Jerry Goldsmith, or a score that insists on a more culturally-informed reading for understanding—any ironic, post-modern, Gen-X film score, for example—is still largely unexplored territory.

Probably the essay that stands out the best on its own in this first part is Tim Anderson’s history of the music for silent film and nickelodeons. Granted, it is less about a theoretical understanding of how the music works and more a sociological examination of the cultural distinctions between high and low culture during the first decades of the twentieth century and how this influenced musical choices. It does question Gorbman’s assumption of the primacy of the visual image, however, and is one of those rare combinations of peerless archival research combined with engaging storytelling.

If I seem to focus disproportionately on the first section of the book, it is because this is the area of film music for which the literature has traditionally been most disappointing. As Dickinson points out in her introduction, although the vast majority of writing has been on orchestral music and composers, it has traditionally been limited to shallow biographies or surface descriptions of the music. The rest of Dickinson’s book is much less problematic. Jeff Smith’s article that opens Part Two, “Banking on Film Music: Structural Interactions of the Film and Record Industries,” is in many ways the heart of the collection. Reprinted from his book Sounds of Commerce, it shows how the modern synergy between a film and its pop soundtrack (commonly thought to be a recent development) can be traced back to the beginning of film’s history. Again, he flawlessly combines archival data with the stories of individual publishing houses to tell a fascinating story.

Highlights from the rest of the book include Dickinson’s own essay, “Pop, Speed and the ‘MTV Aesthetic,’” a discussion of how film style has been influenced by the pop music supposedly subservient to it. Krin Gabbard’s essay “Who’s Jazz, Whose Cinema?” insists on an understanding of early sound “jazz” films within the terms of their own creation, rather than the later, more artistically autonomous definition of jazz that meant the devaluation of these films.

The final section of the book, concerned with the image of the musician in film, contains three strong essays, each devoted to a different aspect of representation. Keir Keightley’s essay, “Manufacturing Authenticity: Imagining the Music Industry in Anglo-American Cinema, 1956–62” deals with that fascinating genre, the “industry insider” picture. He demonstrates the ways these films helped articulate a generation’s concern with their own music’s authenticity, in films such as Expresso Bongo and The Girl Can’t Help It.

Dickinson has done a remarkable thing by combining the voices of the most prominent people working in film music scholarship today. Through a skillful mix of editing and selection, she has pieced together a representative collection of essays that accurately depicts the state of the field. I recommend this collection as a perfect introduction to film music studies: it both demonstrates how much room exists within the field to grow, and more importantly presents the already high standard of research.

Louis Niebur

University of California, Los Angeles

Works Cited

Chion, Michel. Audio-vision: Sound on Screen. Trans. and ed. Claudia Gorbman. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

_____. The Voice in Cinema. Trans. and ed. Claudia Gorbman. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Eisler, Hans. Composing for the Films. London: D. Dobson, 1951.

Goldmark, Daniel. “Happy Harmonies: Music and the Hollywood Animated Cartoon.” Diss. University of California, Los Angeles, 2001.

Goldmark, Daniel and Yuval Taylor, eds. The Cartoon Music Book. Chicago: A Capella, 2002.

Gorbman, Claudia. Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Kalinak, Kathryn. Settling the Score: Music and the Classic Hollywood Film. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

Kassabian, Anahid. Hearing Film: Tracking Identifications in Contemporary Hollywood Film Music. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Smith, Jeff. Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.