In response to questions regarding Luciano Berio’s 1968 Sinfonia, the composer stated “I’m not interested in collages. The references to Bach, Brahms, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, etc. are … little flags in different colours stuck into a map to indicate salient points during an expedition full of surprises” (Dalmonte and Varga 106–107). In Martin Virgo’s response to questions regarding the impetus for Formica Blues, the 1997 debut release of Mono (the pop duo he formed with Siobhan de Maré), one can hear shades of Berio’s explanation when Virgo says “It’s just about the way that the styles have collided … I actually probably like more new music than old … I don’t romanticize the past at all” (“Mono’s Official Webpage”).

release of Mono (the pop duo he formed with Siobhan de Maré), one can hear shades of Berio’s explanation when Virgo says “It’s just about the way that the styles have collided … I actually probably like more new music than old … I don’t romanticize the past at all” (“Mono’s Official Webpage”).

Similar to Berio’s Sinfonia, Formica Blues contains samples of various musical works. Unlike Sinfonia, however, these samples are heterogeneous: they are taken from a variety of musical traditions, including excerpts from Burt Bacharach’s “Walk on By,” John Barry’s “Ipcress File,” Gil Evans’s “The Pan Piper,” Alban Berg’s Lulu Suite, and Arnold Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces, Op. 16.

Virgo insists that Formica Blues “simply evolved from the most played records in his collection, meshing past and future contained within clear pop parameters” (“Mono’s Official Webpage”). Music critic Charles Taylor describes Formica Blues as follows:

What distinguishes the album from a shopping list of mid-60s cool is the enormous affection de Maré and Virgo conjure up for the period they invoke. It’s the lack of irony or distance in that affection that [is] the key to understanding this band.

The language of Virgo and his critics suggests a further correlation with Berio’s description of Sinfonia. Berio disagreed with the “collage” label so often attached to Sinfonia with its implications of “relativizing and recontextualizing” images; rather he believed Sinfonia to be less “a collage of quotations” and more “a homogeneous work that looks within itself” (Dalmonte and Varga 106, 109). Martin Virgo’s emphatic statement that his music is “past and future contained within clear pop parameters” betrays a similar urge towards homogeneity.

However, the structure and content of Mono’s music seems incongruous with Virgo’s own language. For example, a fog of confusion could engulf the listener upon hearing “Hello Cleveland!,” the tenth track of Formica Blues—a song that on the surface sounds homogenous yet paradoxically presents a heterogeneous collage. In a single, instrumental song that lasts under five minutes, Mono samples Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia, Anton Webern’s Six Pieces, Op. 6, Arnold Schoenberg’s Op. 16, and Alban Berg’s Lulu Suite, presumably some of the “most played records in his collection.”

“Hello Cleveland!” begins with an ascending guitar arpeggio punctuated by the strike of a triangle. Although possibly inspired by a moment in Webern’s Six Pieces, this introduction is not a sample but of Virgo’s own creation.1 Several seconds into the song, a solo piano enters with material that, although newly composed, sounds strikingly similar to Erik Satie’s Gymnopédies or Gnoissiennes. A drumbeat in five-four meter accompanies this piano part, which Virgo loops for almost a minute. At this point, he introduces the aforementioned samples, beginning with a one-second sample of the fifth movement from Berio’s Sinfonia. The samples repeatedly follow each other, often punctuated with the one-second Berio sample, until the last minute of the song when the drumbeat ceases and Virgo loops a newly-composed chord progression played on a piano (again reminiscent of Satie) for the final minute of the song. (See Table 1 for a listing of the samples’ origins, their placement within the original work, and their placement within “Hello Cleveland!”)

The function and intended purpose of pastiche in “Hello Cleveland!” becomes highly problematic, primarily because such an endeavor is contingent upon a listener’s familiarity with the sampled material. For the mainstream listener, the samples in “Hello Cleveland!” act at best as “classical music” simulacra—free-floating signifiers that lack a specific referent. For the classical music connoisseur, the samples act not as simulacra, but as direct signifiers that provide semantic counterpoint and add further layers of interpretation to the song.

Mono’s sampling technique balances tentatively between Fredric Jameson’s postmodern “blank parody,” and the modernist aesthetic of borrowing pre-existing material (111–125). In an attempt to explore this nexus of modernist and postmodernist borrowing, I offer two possible interpretations with corresponding listener responses. First, the “connoisseur” perspective: “Hello Cleveland!” is a self-conscious artistic statement through which Mono attempts to position itself as a culminating point in a long and distinguished traditional lineage. By sampling classical works, specifically Berio’s Sinfonia, itself comprised of borrowed materials, Virgo offers a self-reflexive quotation of quotation. In so doing, Virgo constructs his own musical museum, placing himself within the museum’s walls. Such an interpretation echoes a modernist aesthetic of intentional quotation. In the second interpretation, “Hello Cleveland!” is not a self-conscious narrative, but rather a pastiche of various elements that results in a complete collapse of self-conscious dimensions, an “exhilaration of surfaces” (Manuel 233) and little else.2 Virgo does not intend the source of the samples to be recognized, nor, he claims, should there be any meaning attributed to their source or temporal placement.

Consider a broader context for interpretation: Mono’s music can be loosely classified as ambient, a subgenre of electronic dance music, or techno, associated with a subculture of youths who created music in dance clubs and raves in the late 1980s and early 1990s.3 Originally, DJs improvised this music by layering programmed drumbeats over samples of pre-existing material that the DJ then altered through the manipulation of two turntables. Similar to dance or techno, ambient music characteristically consists of a repeating melodic and/or harmonic figure and sparse vocals; yet unlike techno’s quick tempo (100–130 beats-per-minute) articulated by frequent drumbeats, some ambient music is “designed to lull [one’s] mind through more soothing rhythms” (Hilker).4 Furthermore, creators of ambient music sample much of the genre’s musical elements from pre-existing material. Unlike other sample-based genres, including rap and hip hop, ambient artists consistently borrow from the Western classical music tradition. (See Table 2 for a few such examples.)

This kind of borrowing of classical music raises a variety of questions for the modern music scholar and critic. David Toop, one of the few scholarly writers on ambient music, provides the perspective of a subcultural insider—he is both an ambient music producer and fan. In his book Ocean of Sound, Toop describes ambient music as a conflation of often-disparate elements, not unlike a musical landscape filled with borrowed materials. He goes on to chart the genealogy of ambient music, which for Toop began in 1889. He states: “The day when Debussy heard Javanese music performed at the Paris Exposition of 1889 seems particularly symbolic. From that point … accelerating communications and cultural confrontations became a focal point of musical expression” (xi). Toop avoids the traditional distinction between high and low art; rather, he looks across the broad musical spectrum to those figures who worked with musical pastiche, quotation, or borrowing to “communicate” with the audience through “cultural confrontations.” For musicians who compose ambient music, these “cultural confrontations” result in the borrowing and quotation, often via sampling, of classical works.

For Mono, this “confrontation” between high and low art is central to Martin Virgo’s musical background and interests. As a classical pianist trained at London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama, Virgo worked on a variety of dance remix projects with Björk, among other musicians. His work as artist and producer led him to create Mono with singer Siobhan de Maré, a musical outfit that has allowed him to explore his myriad of musical influences. Although the ambient music genre relies heavily on pastiche techniques, the source of the sampled material in “Hello Cleveland!,” as well as its quantity, seems remarkable. The obscurity of the web of samples intimates a secret code of signifiers that begs interpretation and suggests a relationship more nuanced than mere “confrontation” between high and low art. Virgo’s sampled works represent the dominant high modernism of the academy. Indeed, Virgo admires the works of the second Viennese school and confesses that “this isn’t music that tends to rear its head in a lot of popular music, but it’s what I listen to, and I’ve absorbed these influences” (Molineaux).

It seems likely that Virgo took these pieces from separate recordings, thus further demonstrating his diligent intent to borrow from specific works rather than serendipitously finding these pieces on a single compact disc. In all probability, however, Virgo used the Simon Rattle recording of the Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern pieces (which all appear on the same CD), and the Riccardo Chailly recording of Berio’s Sinfonia. Both the Rattle and Chailly recordings are out of print and not easily obtained.

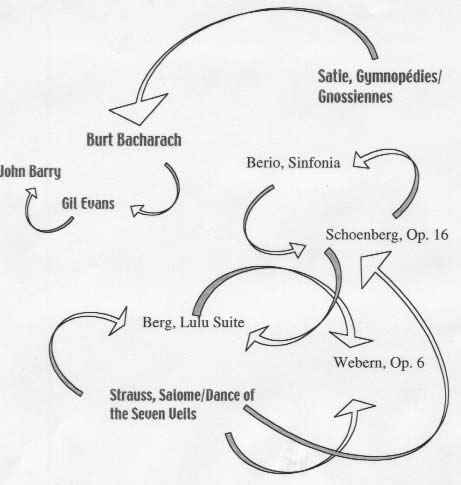

The temporal placement of the samples within “Hello Cleveland!” suggests an intimate understanding of the individual works themselves, as well as the musical tradition of which they are a part. As the song progresses, the proliferation of samples creates a snowball effect, not unlike passages in T. S. Eliot’s The Wasteland—a poem that presents readers with an accumulating field of quotations. The samples of Berio, Berg, Schoenberg, and Webern act as signifiers that, once exposed, offer layers of semantic counterpoint. For example, in the third movement of his Sinfonia Berio incorporates the fourth of Schoenberg’s Op. 16. While Berio blends Schoenberg’s Op. 16 and Debussy’s La Mer with a moment from Berg’s Wozzeck, Virgo uses Schoenberg’s Op. 16 as an introduction to the juxtaposition of Berg’s Lulu Suite and Webern’s Op. 6. Likewise, the sampled flute melody near the song’s beginning shares both the tonic key and melodic contour with the “Dance of the Seven Veils” from Strauss’s Salome, a work that contributed decisively to the creation of the Second Viennese School. Is Virgo playfully commenting on the complex interaction of cause and effect that constitutes the history of Western music? (See Diagram 1. Click here for QuickTime movie illustrating the samples Mono uses in “Hello Cleveland!”)

Diagram 1. Intra- and Intertextual Connections in Mono’s “Hello Cleveland!”

Diagram 1. Intra- and Intertextual Connections in Mono’s “Hello Cleveland!”

There is a tension throughout “Hello Cleveland!” between sampled and newly composed material. What constitutes “original material” is paradoxically quite repetitive—Virgo records and loops short segments of newly-composed music, creating a sense of stasis and inactivity. In contrast, the dynamic and active elements in this piece are, actually, quotations of past fragments—a different kind of repetition. Although Virgo rarely layers samples vertically in time, those that do overlap include the one-second sample of Berio’s Sinfonia—the same quotation that introduces the sample-filled section of “Hello Cleveland!” Taken from Sinfonia’s fifth and final movement, the passage sampled by Virgo begins the recapitulation in Berio’s piece, a repetition of previously-heard material from earlier in Sinfonia. At the same time that this recapitulation is necessarily a kind of repetition, it is also Berio’s literal “re”presentation of this material that makes it new. No longer an item in itself, it is a context-defined and defining moment. Virgo uses the Berio sample as the introduction to his musical landscape of samples with possibly an equivalent result—he announces the beginning of something entirely new, a recapitulation not of previously heard material from Formica Blues, but a recapitulation of previous musics, previous traditions. To use Berio’s phraseology, these one-second Berio samples are the “little flags” that indicate the “salient points” during the listener’s expedition through “Hello Cleveland!”

How does this mirror-like field of quotation function in a hermeneutic framework? In his essay “The Ecstasy of Communication,” Jean Baudrillard laments that “[p]eople no longer project themselves into their objects, with their affects and their representations, their fantasies of possession, loss, mourning, jealousy” (127). On one level, “Hello Cleveland!” involves exactly this kind of postmodern irony.

The above modernist reading necessitates a listener’s recognition and understanding of the pieces sampled in “Hello Cleveland!” These samples create semantic counterpoint for classical music connoisseurs only because they acknowledge the referents and attempt to interpret the new material within the context of these borrowed works—an act that attaches significance to the signifier.

Yet, “Hello Cleveland!” denies even the most astute listener straightforward empathy, or “possession” in Baudrillard’s terms. With each passing moment, the listener becomes increasingly bombarded with signs that, while at first accessible, become inaccessible through surplus. In other terms, it is as if you find yourself at a party with too many people talking at the same time—everyone could be holding great conversations, but their simultaneity may cause you to withdraw. This snowball effect serves only to create a blank state and to distance the listener from the work. Such a result is strikingly similar to the response of the non-connoisseur listener.

If a listener were unacquainted with the particular samples used, the sample-web and its allusions would escape the listener and remain buried. Such a listener does not search for Mono’s impetus behind the sampling of Berg, Webern, and the like, because she may be unaware of the music’s existence; instead, this listener enjoys “Hello Cleveland!” as a sonic landscape, an unmediated journey through various textures and styles.

Virgo also creates this landscape of past music through means other than sampling. As mentioned previously, “Hello Cleveland!” both begins and ends with newly composed material reminiscent of Satie’s piano works. Virgo’s truncation of phrase endings and creation of readily-audible loops transform this newly composed material into samples themselves. For all its jarring elements, however, such a technique results in a seamless combination of newly-composed and sampled material. The lack of stark juxtapositions mirrors Jameson’s hierarchy effacing postmodern ideology. He states, “[artists] no longer ‘quote’ such ‘texts’ as a Joyce might have done, or a Mahler; they incorporate them, to the point where the line between high art and commercial forms seems increasingly difficult to draw” (112). Jameson’s mention of James Joyce here seems particularly appropriate, as Joyce and Martin Virgo both present their audience with a similar contradiction. Joyce’s works tantalize the reader because his quotations never engender a simple effect or a singular meaning. Although he tends to maintain a certain hierarchy in his quotations, he paradoxically encourages the effacement of boundaries and distinctions to the extent that the artist himself would become hidden, unnoticeable. As Joyce writes in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the artist becomes “like the god of creation … within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails” (215). Although it is debatable as to whether or not Joyce accomplished this feat in his works, Virgo seems to disappear and become invisible in “Hello Cleveland!” The notion that through quotation Virgo has constructed a narrative with which he places himself in a tradition of borrowing cannot apply because Virgo becomes lost under a pile of masks. Perhaps Virgo is not an example of Joyce’s “god of creation” since “Hello Cleveland!” resembles less a creation and more an aggregation of elements.

Much of Mono’s discourse supports this reading of “Hello Cleveland!” The nonchalant rhetoric Virgo employs when describing his music, saying it “simply evolved,” that it’s “just about styles colliding,” seems to be a kind of postmodern metaphor of the blank. This reading suits the popular music listener who would recognize the presence of samples, but not recognize a specific sample as a signifier with a particular referent. Such a listener would instead hear these samples as a classical-music simulacra. Most likely, the majority of Mono’s audience fits into this category. All of the samples used in Formica Blues are listed in the album’s liner notes with the exception of those used in “Hello Cleveland!” Although interviewers frequently question the band’s sampling choices, no reviewer has asked Virgo or de Maré about their use of classical music samples on this track or on the album as a whole—perhaps because they do not hear them and are not alerted to their presence through the liner notes. Or, perhaps the fact that they are “classical music” provides enough signification for them.

Certainly this is the case for many critics who have written about Formica Blues. Critic Marcelle Rousseau’s language betrays the recognition of the classical music signifier, but nothing further. She writes, “With the use of traditional and modern instruments as well as several samplings reminiscent of Mission: Impossible or The Twilight Zone, “Hello Cleveland!” progresses through variations of images from Peter and the Wolf to Psycho or the X-Files to Beck.”5 Other critics similarly describe “Hello Cleveland!” as a “puzzling mix” of textures including “orchestral textures” (Remstein). These listeners recognize the object, but not its use. For the listener who does not distinguish between the sampled material and that which is newly composed, both the object and its use go unnoticed, and a potentially multi-dimensional work completely collapses.

At this point both the “amateur” and the “connoisseur” listenings converge. The connoisseur listener follows Virgo down the rabbit hole, entertaining the myriad of intertextual connections that only distance the listener from the work and seem to be merely a chimera. The listener unacquainted with classical music finds the same blank soundscape through the absence of sample recognition. Although Virgo’s intention does not influence the ultimate interpretation of “Hello Cleveland!,” his construction of this piece betrays a certain postmodern urge towards failure. Only through the failure of the intricate sample-web can one begin to listen with a different purpose and perspective.

This urge towards failure contradicts the seemingly-innate need to create a narrative out of musical events. Jean-François Lyotard describes part of The Postmodern Condition as an “incredulity towards metanarratives” (xxiv).6 Certainly the best way to engender a narrative crisis is to give the listener too much—too many disparate elements that defy the cohesive properties of the narrative. This is precisely what Virgo accomplishes: he gives the listener too many signs which cannot be woven into a singular, unified narrative, and, as a result, encourages skepticism. (The obvious irony here being that we deal with this problem through creating yet another narrative.)

Virgo obliquely refers to this crisis of narrative in a discussion of Phil Spector’s trademark “wall of sound” production technique: “I love that whole school of music production where there are so many things going on at once but the overall sound doesn’t seem complicated. It’s so kaleidoscopic, and that’s what I’m really into” (Molineaux). Virgo’s description of Spector’s sound as “kaleidoscopic” seems particularly apt as it connotes exactly those elements that a traditional narrative withholds: freefloating shards of color, tremendous moment-to-moment flexibility, and an organization which collects and quickly disperses its “information” rather than weaving or tying it into inflexible chains.

“Hello Cleveland!” stands as Virgo’s sound kaleidoscope: a collection of disparate elements that, through careful placement, form a surprisingly simple image. The creation of such an image is, however, contingent upon a person swirling the fragments of color about, until a satisfactory structure forms. Without such a medium, what propels the music forward? For Berio, Sinfonia’s web of quotations necessitates the consistent uttering of the verbal tag “keep going” in order to propel the music, to literally keep the piece going, as it provides form and structure from without rather than within. Virgo similarly creates a swarming mass of sound samples that necessitates an ad-hoc scaffold. In this way, the song’s rhythmic propulsion structures the listener’s adventure through Virgo’s quotations and, in that sense, keeps “Hello Cleveland!” going.

–––

Note: An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2001 meeting of the American Musicological Society in Atlanta, Georgia. I would like to thank Seth Brodsky for indulging the conversations that started and propelled this project, and Paul Miller for lending his computer skills.

–––

Sara Nicholson is a doctoral candidate in musicology at the Eastman School of Music where she is working on her dissertation entitled “‘Weapon of Choice’: Intertextuality in Popular Music Since 1990.” She has had papers accepted at the national meeting of the American Musicological Society as well as the US chapter meeting of IASPM (International Association for the Study of Popular Music). She has published articles in the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, volume 3 (2001) and Incestuous Pop: Intertextuality in Recorded Popular Music (forthcoming). Currently she teaches courses in American music and music appreciation at Towson University in Maryland.

–––

Works Cited

Baudrillard, Jean. “The Ecstasy of Communication.” The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Ed. Hal Foster. New York: The New Press, 1983. 126–134.

Dalmonte, Rossana and Bálint András Varga, eds. Luciano Berio: Two Interviews. New York: Marion Boyars, 1985.

Hilker, Chris. The Official alt.rave FAQ. 8 May 1994 <http://www.hyperreal.org/raves/altraveFAQ.html>.

Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism and Consumer Society.” The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Ed. Hal Foster. New York: The New Press, 1983. 111–125.

Joyce, James. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Ed. Richard Ellman. New York: Viking Press, 1964.

Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Manuel, Peter. “Music as Symbol, Music as Simulacrum: Postmodern, Pre-Modern, and Modern Aesthetics in Subcultual Popular Musics.” Popular Music 14.2 (May 1995): 227–239.

“Mono’s Official Webpage.” The Echo Label Website. 20 April 2001 <http://www.mono.echo.co.uk/html/biog.htm>. (No longer online).

Molineaux, Sam. “Martin Virgo of Mono: Recording Formica Blues.” 10 November 2001 <http://www.sospubs.co.uk/sos/jun98/articles/mono.html>.

Remstein, Bob. “CD Reviews: Mono, Formica Blues.” Wall of Sound. 2001 <http://www.wallofsound.go.com/archive/reviews/stories/3398_36Index.html>. (No longer online).

Roseberry, Craig. Review of Formica Blues, by Mono. 20 April 2001 <http://www.djmixed.com>. (No longer online).

Rousseau, Marcelle. “Review: Mono’s Blues Lives Up To Its Name.” Arcade Online 20 February 1998 <http://www.tulane.edu/~tuhulla/19980220/arcade/Mono.htm>. (No longer online).

Taylor, Charles. “Mono Tones: The Pleasure of Formica Blues.” Boston Phoenix (2–9 March 1998). 20 April 2001 <http://www.weeklywire.com/ww/03-02-98/boston_music_l.html>. (No longer online).

Toop, David. Ocean of Sound: Aether Talk, Ambient Sound and Imaginary Worlds. London: Serpent’s Tail, 1995.

Discography

Berg, Alban. Lulu Suite. City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. Cond. Simon Rattle. EMI Records Ltd., 1989.

Berio, Luciano. Sinfonia. Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. Cond. Riccardo Chailly. London Records, 1990.

Mono. Formica Blues. Echo/Mercury Records, 1997.

Satie, Eric. Gymnopédies. Satie: Piano Music. Perf. Frank Glazer, piano. Vox Box, 1990

Schoenberg, Arnold. Five Orchestral Pieces, Op. 16. Cond. Simon Rattle. City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. EMI Records Ltd., 1989.

Webern, Anton. Six Orchestral Pieces, Op. 6. Cond. Simon Rattle. City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. EMI Records Ltd., 1989.

- At 1:36 in the fifth movement of Webern’s Six Pieces, a marimba plays an ascending arpeggio punctuated with a triangle. ↩

- Manuel describes postmodern sampling as follows: “ … in most of these cases, the sampled passages function as simulacra … to be enjoyed for their very meaninglessness, their obvious artificiality, in a characteristically postmodern exhilaration of surfaces” (233). ↩

- While I have chosen to label Mono’s music as “ambient”—a label often used by fans and critics in reference to Mono—this is not a wholly satisfactory designation. Ambient music does not generally have a continuous beat, and the songs usually last far longer than the traditional 3–5 minutes. While “trip hop” perhaps more accurately describes Mono’s sound, in that most of Mono’s songs are short and do contain a dance beat more consistent with trip hop, I feel that ambient better describes the music’s mood and function. Although downtown and ambient both fall under the label of “electronica,” I find this to be an exhausted and relatively meaningless umbrella term that can apply to any and all synthesizer-based music. ↩

- A fairly complete index of these terms, along with definitions and musical examples of dance-related musics can be found at http://www.hyperreal.org/raves/altraveFAQ.html. ↩

- Both Roseberry and Remstein confuse the samples present in “Hello Cleveland!” ↩

- The complete Lyotard quote is as follows: “I define postmodern as incredulity toward metanarratives. This incredulity is undoubtedly a product of progress in the sciences: but that progress in turn presupposes it. To the obsolescence of the metanarrative apparatus of legitimation corresponds, most notably, the crisis of metaphysical philosophy and of the university institution which in the past relied on it. The narrative function is losing its functors, its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal. It is being dispersed in clouds of narrative language elements—narrative, but also denotative, prescriptive, descriptive, and so on” (xxiv). ↩