Introduction

{1} In May 2006, the newly elected leader of the British Conservative Party, David Cameron, appeared on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Disks, where guests are asked to choose eight records they would take with them to a desert island and explain their selection. 1 After almost a decade in opposition, the Conservative Party was widely considered “out of touch” and Cameron used the opportunity to discuss his vision of “compassionate conservatism,” 2 couched within an overview of his favorite bands. Cameron’s castaway playlist included The Smiths, Radiohead, and Pink Floyd. While little was made of the playlist at the time, Cameron’s election to Prime Minister in May 2010 generated new interest in his personal affairs. Cameron’s privileged background together with his government’s unpopular austerity measures, combined to make him a hate figure for the left; his musical tastes have been rebuked by fans, his political opposition, and the artists themselves, as being incompatible with his right-wing political program. 3

Figure 1. David Cameron asked about liking The Smiths at Prime Minister’s Questions, December 18 2010.

{2} Johnny Marr, former songwriter and guitarist of The Smiths, encapsulated this discontent in December 2010 when he tweeted: “David Cameron, stop saying you like The Smiths, no you don’t. I forbid you to like it.” 4

Figure 2. Johnny Marr forbids David Cameron to like The Smiths.

David Cameron, stop saying that you like The Smiths, no you don’t. I forbid you to like it.

— Johnny Marr (@Johnny_Marr) December 2, 2010

There are parallels between David Cameron’s appropriation of The Smiths and Ronald Reagan’s use of Bruce Springsteen. 5 In trying to explain the contradictory plurality of postmodernism, Stuart Hall highlighted Springsteen as a phenomenon that could be read “in at least two diametrically opposed ways,” on account of his being “in the White House and On The Road.” 6

{3} This article examines music’s role in the creation and maintenance of collective identity. It explores why David Cameron’s musical tastes elicit such an emotive response from fans, as well as the artists themselves, and why they consider his stated musical preferences to be disingenuous. The article aims not to sketch out the traits of an “ideal listener,” nor to rehash Adorno’s debates around “expert” and “emotional” listeners, wherein the structural and technical understanding of the former is prized over the simple enjoyment of the latter. 7 Instead, it seeks to focus on an example of someone whose listenership fans deem “inauthentic.” This negative approach seeks to further problematize notions of authenticity by extending the debate into the realm of the listener, using Cameron as its case study.

Towards An Authentic Listener

{4} In “Have I the Right? Legitimacy, Authenticity and Community in Folk’s Politics,” Steve Redhead and John Street discuss how, during the late 1980s, popular musicians in Britain drew on a folk ideology that stressed the connection between the artist and “the people.” They explore the notion of an artist’s career being rooted in a specific audience; the artist’s faithfulness to the music of their roots; and their representation of the sociological origins of said roots. 8 The authors favor the notion that the artist creates the audience, over their emerging from the people, yet ignore the tensions between those within the listening community.

{5} Thirteen years later, in the same journal, Allan Moore built upon Redhead and Street’s argument, exploring a similar conception of authenticity that focuses on the artist’s accurate portrayal of their own position; those “absent” from such a situation; and their sincere depiction of the culture in which they operate and those inhabiting it. Moore rejected Born and Hesmondhalgh’s assertion that authenticity be “consigned to the intellectual dust-heap”, 9 but stressed that the focus of authenticity should “shift from consideration of the intention of various originators towards the activities of various perceivers.” 10 Moore discusses the relationship between appropriation and authenticity, agreeing with Richard Middleton’s assertion that appropriation is the hallmark of authenticity. 11 He dedicates the article to who instead of what is being authenticated, yet, despite his rigorous examination of latitudinal listener-authentication, between listener and artist, he offers little discussion of an “authentic listener” and how listeners authenticate each other, longitudinally. Moore returns to the discussion around listener authentication in his 2012 book Song Means, where he explores what it means to experience a song and stresses music’s role in shaping who we believe ourselves to be. The locus of Moore’s book is “music as it sounds,” not with the representation of music and its different listener types. 12 Again, the concept of longitudinal listener-authentication remains underdeveloped; Moore’s gaze fixed upward on how listeners authenticate artists. This article explores the contestation around whether a musical utterance can be sincerely heard, examining the disconnect between the artist and the “inauthentic listener,” as well as the tension between “roots listeners” and those outside this group. 13

The Embodiment of a Social Identity

Figure 3. Morrissey performs at Belfast’s Odyssey Arena, March 24 2015. Photograph by Stephen R. Millar.

{6} The Smiths were a critically acclaimed English indie rock band that achieved cult-status within the five years they were musically active. Formed in 1982, the band recorded a mere four studio albums, with modest commercial success, yet their influence and legacy is second only to The Beatles in their native Britain. Morrissey, the band’s frontman, remains a cultural icon. Following The Smiths’ 1987 break-up, Morrissey embarked upon a solo career that has spanned some ten studio albums and several controversies over his militant stance on animal rights, his distain for the royal family, and his hatred of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Although many on the left opposed Thatcher’s neoliberal philosophy of market deregulation and welfare dismantlement, Morrissey was particularly caustic in his critique. Following the IRA’s attempt to assassinate Thatcher at the 1984 Conservative Party conference, where five were killed and thirty-one injured, Morrissey quipped: “The sorrow of the IRA Brighton bombing is that Thatcher escaped unscathed.” 14

{7} In his discussion of music and identity formation, Martin Stokes argues that “[f]or regions and communities within the context of the modernizing nation-state that do not identify with the state project, music and dance are often convenient and morally appropriate ways of asserting defiant difference.” 15 Prior to forming The Smiths, Morrissey was unemployed and Johnny Marr worked as a shop assistant. Both came from working class communities in the economically depressed North-West of England, which was among the areas hardest hit by Margaret Thatcher’s economic policies. 16 Music was not only a convenient way of asserting their defiant difference; their relatively powerless position within society was a key factor in their embodiment of a social identity that opposed Thatcher’s Britain culturally and politically, enabling them to “articulate a contradictory narrative [for] the marginalized . . . . [i]n a society where the hegemonic discourse is produced by the upper and middle classes.” 17

{8} Following Benjamin, 18 Robin Ballinger argues that mass art can be used as a form of resistance whereby “the music becomes a vehicle through which the oppressed recognize each other and become more aware of their subordination.” 19 However he is quick to concede that music can lose its capacity for resistance through misappropriation. Interestingly, the example he cites is—again—the British Conservative Party which—again—samples an artist from a working-class background in the North-West of England: John Lennon. Ballinger’s point is that by appropriating Lennon’s “Imagine,” which, he argues “once marked the radical impulse of a generation,” 20 the Conservative Party altered its original meaning and sapped the song of its political potency. Ballinger considers such appropriation to be part of a larger issue whereby upon achieving commercial success political songs, and their artists, are damaged; their being used by powerful institutions further exacerbates this disconnect.

{9} The Conservative Party has never used The Smiths’ music in an election campaign; the connection is merely that David Cameron is a fan. Nevertheless, Johnny Marr publicly forbid Cameron like The Smiths. In keeping with Bourdieu’s doxa, 21 whereby any community that feels threatened by others, who affect its reputation, values, or beliefs, tends to protect itself by producing a defensive discourse for orthodoxy, the forcefulness of Marr’s response is as much a recognition of Cameron’s ability to reduce the political power of his music, as a personal distaste at a right-wing politician enjoying his work.

The Epitome of Privilege

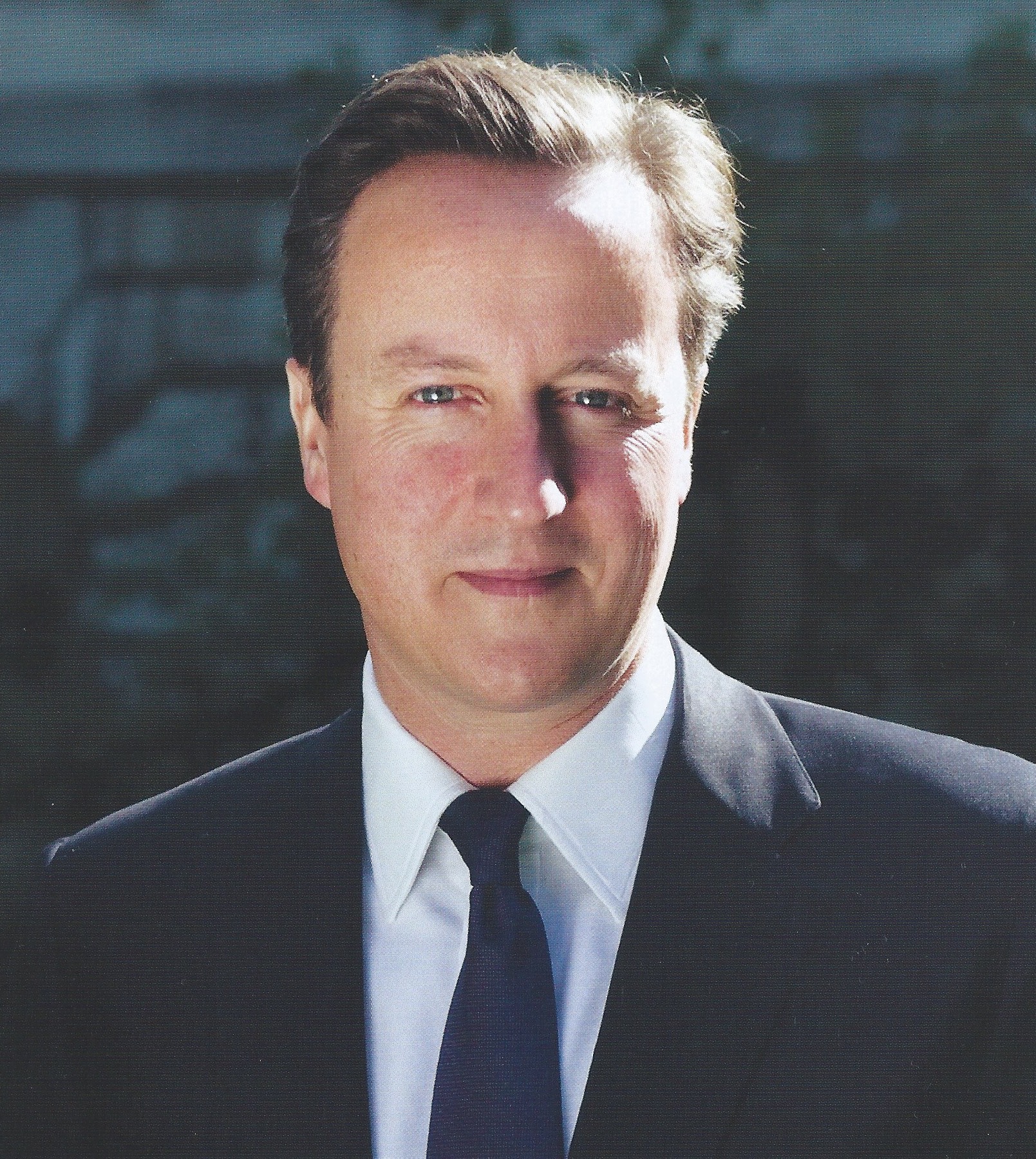

Figure 4. Prime Minister David Cameron. Photograph supplied by The Direct Communications Unit, 10 Downing Street. Used with permission.

{10} David Cameron’s father was a stockbroker, his mother a magistrate and his family have ancestral ties to the British monarchy; he was educated at Eton, and Oxford University. The majority of his Cabinet are millionaires, whose combined personal wealth is almost £70 million. 22 Despite his privileged background Cameron is a vocal supporter of meritocracy; despite professing to be a Thatcherite, 23 he professes to be a fan of The Smiths.

{11} In the comments section beneath a recent online article in The Guardian, entitled “David Cameron to Smiths: what difference does it make?”, “Wireinexile” wrote: “You can’t forbid him from liking the Smiths. But either he doesn’t believe in his own policies or doesn’t understand the music. Either way, he is a prick.” 24 The unequal distribution of cultural knowledge or “cultural capital,” reinforces and, to some extent, creates the boundaries between social classes. Cameron’s lack of common origin or shared characteristics with The Smiths’ fan-base—in other words his lack of identification—challenges, according to Stuart Hall, “the natural closure of solidarity and allegiance established on this foundation.” 25

{12} Wireinexile’s emotive response is likely the result of their absorption of The Smiths’ songs into their life, 26 and, according to Denora, their appropriating the band’s music as a “resource for the ongoing constitution of themselves and their social psychological, physiological and emotional states,” 27 where they use “self-regulatory strategies and socio-cultural practices for the construction and maintenance of mood, memory and identity.” 28 Moore’s notion that “who you believe yourself to be is partly founded on the music you use, what you listen to [and] what values it has for you,” 29 further explains the discomfort many Smiths fans feel in sharing the musical preferences of David Cameron. 30 Wireinexile’s argument belittles Cameron for failing to grasp what the music is really about, thus the unsuitable fan is denied admission to the larger social alignment and its identity is kept intact.

{13} But what if he did get it? What if David Cameron listened to The Smiths and, despite his markedly different upbringing and life experiences, liked it, or worse, related to it? Indeed, isn’t that why Wireinexile adopted such confrontational language, or why Johnny Marr commented at all, because they felt threatened by Cameron’s liking their music? Both reactions demonstrate a realization that in addition to the narrowly materialist conception of power and inequality that Cameron enjoys over most Smiths fans in the traditional sense, his professed love of the band further extends his power through this possession of social and cultural capital. It can also be read as an example of Cloonan’s thesis that “the strategic deployment of popular music and control of mass media have become ever more powerful tools in the State’s arsenal.” 31 Given that identities are, ultimately, constructed through difference, 32 Cameron’s appropriation of The Smiths challenges the band’s fan-base, while simultaneously undermining their ability to use music as a means of political resistance. 33 This explains the fan’s unease and their need to place Cameron’s liking The Smiths into a binarism: either he doesn’t believe in his own policies, or he doesn’t understand the music.

Digitally Enhanced/Politically Reduced

{14} In their 2010 book Why Pamper Life’s Complexities? Sean Campbell and Colin Coulter offer another explanation as to how and why David Cameron can, “quite incredibly,” 34 like The Smiths. 35 They find Cameron’s “very public declarations of devotion to the band” as being symptomatic of a “repackaged” version of The Smiths, drained of their political import. 36 The argument is laid out under the Benjaminesque subheading: “The work of pop in the age of digital reproduction:”

The version of the group that has gained currency of late is sufficiently sanitised to enable their songs to be enjoyed by those who might ordinarily be repelled by their politics. Even the most prominent Conservative in the United Kingdom is, remarkably, both willing and “entitled” to be a Smiths fan.37

{15} Yet this all presupposes that Cameron became a fan of The Smiths the second time around. Cameron was a teenager when The Smiths were at their peak and it seems likely it was then that he was exposed to their music, decoding the songs in relation to his own social context. 38 To assert Cameron became a fan of The Smiths during their resurgence, once their music had—supposedly—been purged of its socio-historical and political import, seems too convenient. Worse, neither author offers any evidence to support these claims. Campbell and Coulter admit that their book makes “little attempt to disguise their passion for, or pleasure in, their subject matter.” 39 Yet, despite couching it within academic language, Campbell and Coulter make the same fundamental point as Wireinexile: Cameron doesn’t get it. The three are united in their unwillingness to allow Cameron’s accession to fandom and conform to cultural essentialisms that “sounds must somehow ‘reflect’ or ‘represent’ the people.” 40 That trained academics succumb to the same subjective pitfalls as fervent fans is indicative of music’s power over us and its important role in shaping our identity.

Electioneering

{16} Nicholas Cook 41 and Bethany Klein 42 both demonstrate how television adverts use music to heighten their product’s appeal and imbue it with the transcendental. 43 Politicians are increasingly using music in a similar fashion, appropriating music for social and cultural capital. While this is not a new phenomenon, it has assumed new importance with the re-examining of copyright laws and notions of musical ownership in the digital age.

{17} In a February 2013 issue of Dazed & Confused, Radiohead’s Thom Yorke threatened to “sue the living shit” out of David Cameron, should he use any of Yorke’s music in his election campaigns. 44 The interview formed part of the promotion for Yorke’s new album, Atoms For Peace, and his outburst received widespread coverage across the British press. Yorke’s insistence that Cameron not use his music was the focus of the story, his releasing a new album being relegated to the end of most articles. 45 Yorke’s response was symptomatic of the way many artists react to those they believe to be misappropriating their music and its message. Recently there has been a move towards artists asserting themselves and demanding that their music is not used to lend support to causes they themselves condemn. This demonstrates a realization that when an artist’s music is appropriated, they themselves are appropriated and their music becomes polarized along party-political lines. 46

{18} In the U.S., Survivor, Talking Heads, and Jackson Browne have all taken legal action against politicians they felt had misappropriated them and their music. 47 In a letter to Mike Huckabee, a Republican politician using Boston’s “More Than A Feeling” as his campaign song, Tom Scholz wrote: “By using my song and my band’s name BOSTON, you have taken something of mine and used it to promote ideas to which I am opposed.” 48 As someone espousing left-wing ideals, Scholz took exception at a Republican using his music to promote right-wing policies. 49 More recently, business mogul and presidential hopeful Donald Trump’s use of Neil Young’s “Rockin’ In The Free World” and R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” at his campaign rallies saw both artists issue cease-and-desist orders, with R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe responding via band mate Mike Mills’ twitter account: “‘Go fuck yourselves, the lot of you–you sad, attention grabbing, power-hungry little men. Do not use our music or my voice for your . . . moronic charade of a campaign.’–Michael Stipe” 50 Figure 5. R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe tweets in opposition to his voice and music being used by Donald Trump via bass player Mike Mills’ twitter page.

“Go fuck yourselves, the lot of you–you sad, attention grabbing, power-hungry little men. Do not use our music or my voice for your 1) — Mike Mills (@m_millsey) September 9, 2015

…moronic charade of a campaign.”–Michael Stipe

— Mike Mills (@m_millsey) September 9, 2015

{19} Back in the UK, Thom Yorke’s threat to “sue the living shit” out of David Cameron likely stems from an event in 2010, when Cameron’s Conservative Party appropriated British band Keane’s hit single “Everybody’s Changing” during their election campaign. The song was Keane’s breakthrough single and the band was lauded for its “unusual” absence of a guitarist—its comprising a singer, pianist, and drummer. 51 “Everybody’s Changing” embodied the band’s rejection of the traditional rock line-up and was associated with offering something “rare” and “new.” 52 Like the British Labour Party’s use of D-ream’s “Things Can Only Get Better,” the song seems an obvious choice, given its emphasis on movement and progression. However, Keane were reportedly “horrified” and its drummer took to Twitter to distance the band from the Conservative Party, expressing his disapproval about the way the song had been used. 53

Figure 6. Keane Drummer Richard Hughes Tweets his opposition to The Conservatives.

told the tories played keane at their manifesto launch. am horrified. to be clear – we were not asked. i will not vote for them. — Richard Hughes (@Richard_H) April 13, 2010

{20} It is telling that the band felt compelled to clarify its position on the matter as they clearly believed the Conservative Party were appropriating more than just a song. As Negus writes: “Music is not simply received as sound, but through its association with a series of images, identities and associated values, beliefs and affective desires.” 54 By choosing “Everybody’s Changing,” Cameron and his “detoxified” Conservative Party appropriated the song’s catchiness, its popularity and, in a deeper sense, the band’s challenge and triumph over pre-existing norms. The Conservative Party did not ask Keane’s permission to use “Everybody’s Changing,” nor did it tell the band of its decision to use it: it is unsurprising they felt misappropriated. As Johnson and Cloonan write: “The idea that one no longer has ownership of one’s own sounds is a profound and painful violation.” 55

{21} It could be argued that such controversies provide welcome attention for the artist, confirming Oscar Wilde’s aphorism “there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” 56 Yet this seems unlikely. Both Keane and Thom Yorke were well-established acts and, arguably, did not need such negative attention at the time their songs were used. Further, implicit within their NME interview was the recognition that Keane were powerless to stop the Conservatives from using their music. The Conservative Party did not use the song in political broadcasts, or television commercials, it was used at a private Party conference, and thus there were no copyright issues. In the U.S., the band could have issued a cease-and-desist order, such as that delivered to Republican Presidential nominee Mitt Romney over his use of Silversun Pickups’ “Panic Switch”, yet this legal mechanism does not exist in the UK. 57 Rather, the Conservatives were entitled to use the song, provided they paid the appropriate fees to Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL) and the Performing Right Society (PRS). As such, Thom Yorke’s posturing could be read as recognition of his powerlessness to prevent Cameron appropriating his music in this fashion. Yorke’s attempt to disassociate himself from David Cameron is particularly interesting given that, unlike Keane, he seems to have had some semblance of a relationship with Cameron, prior to his ascension to Prime Minister.

{22} During his appearance on Desert Island Disks, Cameron chose Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees” as one of his most indispensable songs. Asked to justify his choice, Cameron provided the following explanation:

Radiohead’s one of my favorite bands and “Fake Plastic Trees” is a beautiful song. I went to a Radiohead concert the other day, met Thom Yorke and . . . sent this sort of sad letter saying ‘I’d love to come to the concert, thank you for inviting me. p.s. Please play [“Fake Plastic Trees”], my favorite song,’ and he did.”58

{23} It is perhaps unsurprising that Yorke made no mention of his inviting Cameron to a Radiohead gig in his recent interview with Dazed & Confused. Instead, when asked: “Does the fact that your music attracts everyone from teenagers and middle-aged dads to bankers and prime ministers annoy or delight you?” Yorke employed a similar argument to that used by Wireinexile and Campbell and Coulter, replying: “I can’t say I love the idea of a banker liking our music, or David Cameron. I can’t believe he’d like King of Limbs much.” 59 Once again, Cameron is charged with “not getting it.”

Conclusions

{24} The artists discussed in this article share a progressive political platform and, perhaps more importantly, they share the image of being progressive. Yet the relationship between The Smiths, Radiohead, and David Cameron forms part of a larger debate on how artists develop and maintain social and cultural capital. The dialectical position between these artists and society’s prevailing power structures is one they must maintain, despite an economic detachment from their traditional social alignment. Wireinexile and Campbell and Coulter deny Cameron’s ascension to Smiths fandom by employing the binarism: either he doesn’t believe in his own policies, or he doesn’t understand the music. Their insistence that Cameron’s right-wing political program is incompatible with his liking The Smiths chimes with the notion of doxa Bourdieu develops in relation to social space and the homology between spaces in Distinction. 60 Furthermore, it underlines Stokes’ assertion that music can embody a social identity. Cameron’s professing to like The Smiths challenges the perceived homogeny of the band’s fan-base and undermines its political quality.

{25} The debate over David Cameron’s appropriation of The Smiths illustrates a need to re-examine the notions of authenticity promoted by Redhead and Street through exploring the disconnect between “roots listeners” and other listener types. Moore’s contention that the authenticity debate be more listener-orientated was a welcome development, yet his focus remained largely on how the audience authenticates the performer, not itself. Benjamin recognized the importance of authenticity in art when he wrote that without it, the social function of music is revolutionized and instead of being founded on ritual, it is based on politics. 61 The emotive response following Cameron’s professed musical preferences demonstrates the importance of music in the formation of identity and how listening communities—as well as the artists themselves—police their ranks. Negus’ finding that music is greater than sound, and that its use appropriates identities, associated values and affective desires, has now been recognized by the American courts. As politicians increasingly attempt to “out-popularize” each other, it seems likely that music will become a key battleground in the fight for political power and, as such, that the debate over authentic and inauthentic listeners will continue for some time.

Stephen R. Millar (@StephenRMillar) is a final year Ph.D. student in Ethnomusicology, at Queen’s University Belfast, whose research focuses on political music and popular culture, stretching from broadside ballads in the Age of Revolution to contemporary conflicts involving music, ethno-nationalism, and identity politics. He is particularly interested in the use of Loyalist and Republican music in Britain, Ireland, and North America and has published articles in the journals Music & Politics and Scottish Affairs. Stephen’s doctoral thesis, funded by the AHRC, is a comparative study of Irish Republican music in Belfast and Glasgow that explores how songs are used as a means of multimodal resistance against the hegemonic power of the British State.

The author would like to thank Marilou Polymeropoulou for her comments and suggestions.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. Introduction to the Sociology of Music, translated by E.B. Ashton. New York: Seabury Press, 1976.

. “On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening.” In Essays on Music, edited by Richard Leppert, translated by Susan H. Gillespie, 288-315. London: University of California Press, 2002.

Balinger, Robin. “Politics.” In Key Terms in Popular Music and Culture, edited by Bruce Horner and Thomas Swiss, 57-70. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1999.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility.” In The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility And Other Writings On Media, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty and Thomas Levin, 19-55. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Born, Georgina and David Hesmondhalgh. “Introduction: On Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music.” In Western Music and Its Others: Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music, edited by Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh, 21-31. Berkeley, CA; London: University of California Press, 2000.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Campbell, Sean and Colin Coulter. “Why pamper life’s complexities?: an introduction to the book” in Why Pamper Life’s Complexities?: Essays on The Smiths, edited by Sean Campbell and Colin Coulter, 1-21. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010.

Cloonan, Martin. “Introduction.” In Policing Pop, edited by Martin Cloonan and Reebee Garofalo, 1-9. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2003.

. Popular Music and the State in the UK: Culture, Trade or Industry? Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007.

Cook, Nicholas. Analysing Musical Multimedia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Comaroff, Jean. Body of Power, Spirit of Resistance: The Culture and History of a South African People. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Cusick, Suzanne. “Music as torture/Music as a weapon,” Transcultural Music Review, 10, 2006.

DeNora, Tia. Music in Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Devereux, Eoin, Aileen Dillane, and Martin Power. “Introduction: But Don’t Forget The Songs That Made You Cry and the Songs that Saved Your Life…” In Morrissey: Fandom, Representations and Identities, edited by Eoin Devereux, Aileen Dillane, and Martin Power. Bristol: Intellect, 2011.

Frith, Simon. “Music and Identity.” In Questions of Cultural Identity, edited by Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay, 108-127. London: Sage, 1996.

Fryer, Peter. Rhythms of Resistance: African Musical Heritage in Brazil. London: Pluto, 1996.

Grossberg, Lawrence. “On Postmodernism and Articulation: An Interview with Stuart Hall,” edited by Lawrence Grossberg. Journal of Communication Enquiry 10/2 (1986): 45-60.

Hall, Stuart. “Introduction: Who Needs Identity?” In Questions of Cultural Identity, edited by Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay. London: Sage, 1996. 1-17.

. “Encoding/decoding”. In Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972-79, edited by Stuart Hall, Dorothy Hudson, Andrew Lowe, and Paul Willis. London: Routledge, 2005. 117-127.

Johnson, Bruce and Martin Cloonan. Dark Side of the Tune: Popular Music and Violence. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009.

Klein, Bethany. As Heard On TV: Popular Music In Advertising. Farnham: Ashgate, 2009.

Krigsman, Flore. “Section 43(A) of the Lanham Act as a Defender of Artists; ‘Moral Rights’” The Trademark Reporter, 73 (1983): 251.

Moore, Allan. “Authenticity as Authentication.” Popular Music, 21/2 (2002): 209-223.

. Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012.

Negus, Keith. Producing Pop: Culture and Conflict in the Popular Music Industry. London: E. Arnold, 1992.

Power, Martin, Aileen Dillane and Eoin Devereux. “A Push and A Shove and the Land Is Ours: Morrissey’s Counter-Hegemonic Stance(s) on Social Class.” Critical Discourse Studies 9/4 (2012): 375-392.

Redhead, Steve and John Street. “Have I the Right? Legitimacy, Authenticity and Community in Folk’s Politics.” Popular Music 8/2 (1989): 177-184.

Rogan, Johnny. Morrissey & Marr: The Severed Alliance. London: Omnibus Press, 1992.

Seymour, Richard. The Meaning of David Cameron. Winchester: Zero Books, 2010.

Snowsell, Colin. “Fanatics, Apostles and NMEs.” In Morrissey: Fandom, Representations and Identities, edited by Eoin Devereux, Aileen Dillane, and Martin Power. Bristol: Intellect, 2011.

Stokes, Martin. “Introduction: Ethnicity, Identity and Music.” In Ethnicity, Identity and Music, edited by Martin Stokes, 1-27. Oxford: Berg, 1994.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Grey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Endnotes

- Sue Lawley, “Rt Hon David Cameron MP,” Desert Island Disks, May 28, 2006, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/features/desert-island-discs/castaway/8d5bcfbc#p0093vjz. ↩

- George W. Bush introduced this phrase during his 2000 election campaign, via Marvin Olasky, and Cameron subsequently adopted it. For a detailed explanation of “compassionate conservatism” see Richard Seymour, The Meaning of David Cameron (Winchester: Zero Books, 2010). ↩

- This stands in stark contrast to President Barack Obama, whose partial rendition of Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” at a New York fundraiser was praised by the artist and listeners alike. See Adam Goldberg, “Obama Sings Al Green’s ‘Let’s Stay Together’ At Apollo Theatre In Harlem,” Huffington Post, January 20, 2012, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/01/20/obama-al-green-apollo-theater_n_1218070.html. ↩

- Johnny Marr, Twitter post, December 2, 2010, 7:41 a.m., http://twitter.com/Johnny_Marr ↩

- It should be noted that Reagan did not profess to be a fan of Springsteen’s music; he merely invoked the artist’s name at an election campaign in Springsteen’s home state of New Jersey, towards the end of his 1984 election campaign. That some on the American right have appropriated “Born in the USA” is due their focusing on its rousing chorus, at the expense of its anti-war verses. For more, see John Perich, “Born in the USA: Our Most Misappropriated Patriotic Song?” Overthinking, July 3, 2009, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.overthinkingit.com/2009/07/03/born-in-the-usa-our-most-misappropriated-patriotic-song/. ↩

- Lawrence Grossberg, “On Postmodernism and Articulation: An Interview with Stuart Hall,” Journal of Communication Enquiry, 10/2 (1986), 50. ↩

- Theodor W. Adorno. Introduction to the Sociology of Music, trans. E.B. Ashton. (New York: Seabury Press, 1976). ↩

- Steve Redhead and John Street, “Have I the Right? Legitimacy, Authenticity and Community in Folk’s Politics,” Popular Music, 8/2 (1989), 180. ↩

- Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh, “Introduction: On Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music,” in Western Music and Its Others: Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music, ed. Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh, (Berkely, CA; London: University of California Press, 2000), 30. ↩

- Allan Moore, “Authenticity as Authentication,” Popular Music, 21/2 (2002): 221. ↩

- Ibid., 219. ↩

- Allan Moore, Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song, (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 5. ↩

- While Adorno wrote about different modes of listening at length, his focus was on what the listener heard, or didn’t, as opposed to what the listening community thought of the individual and what they did or did not hear. See Theodore W. Adorno, “On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening,” in Essays on Music, ed. Richard Leppert, trans. by Susan H. Gillespie. (London: University of California Press, 2002), 288-315. ↩

- Megan Conway, “Morrissey’s 15 Most Outrageous Quotes,” Rolling Stone, March 6, 2013 accessed March 8, 2015, http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/morrisseys-15-most-outrageous-quotes-20130306. ↩

- Martin Stokes, “Introduction: Ethnicity, Identity and Music,” in Ethnicity, Identity and Music, ed. Martin Stokes, (Oxford: Berg, 1994), 1-27 ↩

- Johnny Rogan, Morrissey & Marr: The Severed Alliance, (London: Omnibus Press, 1992). ↩

- Martin Power, Aileen Dillane and Eoin Devereux, “A Push and A Shove and the Land Is Ours: Morrissey’s Counter-Hegemonic Stance(s) on Social Class”, Critical Discourse Studies, 9/4 (2012): 379. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility,” in The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility And Other Writings On Media, ed. Michael W Jennings, Brigid Doherty and Thomas Levin, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 19-55. ↩

- Robin Ballinger, “Politics”, in Key Terms in Popular Music and Culture, ed. Bruce Horner and Thomas Swiss, (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1999), 61. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, trans. Richard Nice, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977). ↩

- Christopher Hope, “Exclusive: Cabinet is worth £70 million,” The Telegraph, May 27, 2012, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/9290520/Exclusive-Cabinet-is-worth-70million.html. ↩

- Seymour, The Meaning of David Cameron, 3. ↩

- Wireinexile (pseud), February 19, 2012 (9:37 p.m.) comment on Ben Quinn “David Cameron to Smiths: what difference does it make?” The Guardian, February 19 2013, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/feb/19/david-cameron-smiths-what-difference. ↩

- Stuart Hall, “Introduction: Who Needs Identity?”, in Questions of Cultural Intimacy, ed. Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay (London: Sage, 1996), 2. ↩

- Simon Frith, “Music and Identity,” in Questions of Cultural Intimacy, ed. Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay (London: Sage, 1996), 121. ↩

- Tia Denora, Music in Everyday Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 47. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Moore, Song Means, 1. ↩

- Snowsell observes that, “When the textual meaning, implicit and explicit, offered through the singer or performer changes, it’s not just s/he who has changed; all of the audience who accepts uncritically the shift will necessarily have changed as well” (Snowsell, 2011:78). As such, Wireinexile’s criticism could be read as a reaction to, and move against, such changes to The Smiths’ topographical audience-scape. ↩

- Martin Cloonan, “Introduction,” in Policing Pop, ed. Martin Cloonan and Reebee Garofalo (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press), 1. ↩

- Hall, “Introduction”, 4. ↩

- For a more detailed exploration of culture as resistance see Jean Comaroff, Body of Power, Spirit of Resistance: The Culture and History of a South African People (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985) and Peter Fryer, Rhythms of Resistance: African Musical Heritage in Brazil (London: Pluto, 2000). ↩

- Sean Campbell and Colin Coulter, “Why pamper life’s complexities?: an introduction to the book,” in Why Pamper Life’s Complexities?: Essays on The Smiths, ed. Sean Campbell and Colin Coulter (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010), 9. ↩

- There is a growing amount of research literature on Morrissey and The Smiths from both trade and academic publishers. Aside from Morrissey’s own book Autobiography (London: Penguin Classics, 2013) see also Julian Stringer, “The Smiths: Repressed (But Remarkably Dressed),” Popular Music, 11/1 (1992); Nadine Hubbs “Music of the ‘Fourth Gender:’ Morrissey and the Sexual Politics of Melodic Contour,” in Bodies of Writing, Bodies in Performance (New York: New York University Press, 1996); Taina Viitamäki, “I’m Not the Man You Think I Am: Morrissey’s fourth gender,” Musical Currents, 3 (1997); Nabeel Zuberi, “The Last Truly British People You Will Ever Know: The Smiths, Morrissey and Britpop,” in Sounds English: Transnational Popular Music (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001); Pierpaolo Martino, “I am a living sign: a semiotic reading of Morrissey,” International Journal of Applied Semiotics, 6/1 (2007); Michael Bracewell England is Mine: Poplife in Albion (London: Faber and Faber, 2009); Gavin Hopps Morrissey: The Pageant of His Bleeding Heart (London and New York: Continuum, 2009); Simon Goddard, Mozipedia: The Encyclopaedia of Morrissey and the Smiths (London: Ebury, 2012); Tony Fletcher, A Light That Never Goes Out: The Enduring Saga of The Smiths, (London: Heinemann, 2012). ↩

- Ibid., 8. ↩

- Ibid., 10. ↩

- Stuart Hall, “Encoding/decoding”, in Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972-79, ed. Stuart Hall, Dorothy Hudson, Andrew Lowe, and Paul Willis (London: Routledge, 2005), 117-127. ↩

- Ibid., 11. Devereux, Dillane, and Power identify similar difficulties in the introduction to their 2011 edited volume Morrissey: Fandom, Representations and Identities. ↩

- Frith, “Music and Identity,” 108. ↩

- Nicholas Cook, Analysing Musical Multimedia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). ↩

- Bethany Klein, As Heard On TV: Popular Music In Advertising (Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2009). ↩

- Pictorial art can be similarly appropriated for commercial gain. In the French juxtaposition case of 1971, Henri Rousseau’s granddaughter brought an action against a Paris department store that had used the painter’s work in a window-display alongside goods it was selling. Despite Rousseau’s copyright protection ending in 1960, the court ruled in his granddaughter’s favor, his “moral right, being perpetual and descendible, continued in force and in the control of his heirs.” See Flore Krigsman, “Section 43(A) of the Lanham Act as a Defender of Artists; ‘Moral Rights,’” The Trademark Reporter, 73 (1982): 73. ↩

- David Noakes, “Splitting Atoms: Thom Yorke,” Dazed & Confused, February 2013, accessed February 14 2014, http://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/15601/1/splitting-atoms-thom-yorke. ↩

- See, for example, Matilda Battersby, “Radiohead’s Thom Yorke would ‘sue the s*** out of David Cameron’ if Tories used his music,” Independent, January 17, 2013, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/radioheads-thom-yorke-would-sue-the-s-out-of-david-cameron-if-tories-used-his-music-8455815.html; Sean Michaels, “I’ll sue David Cameron if he uses our music,” Guardian, January 17, 2013, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/jan/17/radiohead-thom-yorke-david-cameron; and No byline, “Thom Yorke would ‘sue the living shit’ out of David Cameron if Tories used his music,” NME, January, 17 2013, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.nme.com/news/radiohead/68218. ↩

- Following a cease-and-desist order from Silversun Pickups, American Presidential candidate Mitt Romney sought the support of the right-wing Kid Rock. Not only did Rock agree to Romney’s using his “Born Free” as his election campaign song, he performed with Romney at various Republican rallies. See Matthew Perpetua, “12 Songs Republicans Used Without Permission,” BuzzFeed, August 17, 2012, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.buzzfeed.com/perpetua/12-songs-republicans-used-without-permission. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Andy Green, “‘More Than A Feeling’ Writer Says Mike Huckabee Has Caused Him ‘Damage,’” Rolling Stone, February 14, 2008, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/more-than-a-feeling-writer-says-mike-huckabee-has-caused-him-damage-20080214. ↩

- The debate over how music is used now extends to its role in torture. Rage Against The Machine, R.E.M. and Pearl Jam are just some of the bands campaigning against the American government, which has been using their songs to torture detainees at the infamous Guantanamo Bay. “Musicians Standing Against Torture,” New Security Action, accessed February 15, 2014, http://newsecurityaction.org/pages/music-used-to-torture. For more information on music as torture see Suzanne Cusick, “Music as torture/Music as a weapon,” Transcultural Music Review, 10 (2006) and Bruce Johnson and Cloonan, Dark Side of the Tune: Popular Music and Violence, Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2009). ↩

- For more on U.S. politicians’ use of popular music, see Kimberlianne Podlas “Off the Campaign Trail and Into the Courthouse: Does a Political Candidate’s Use of a Song Infringe on the Performer’s Trademark?”, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59/1 (2015) and Dana Gorzelany-Mostak “‘I’ve Got a Little List’: Spotifying Mitt Romney and Barack Obama in the 2012 U.S. Presidential Election,” Music & Politics, 9/2 (2015). ↩

- “Keane.” Encyclopedia of Popular Music, 4th ed. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed March 2, 2013, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/epm/74496. ↩

- Ian Youngs, “Sound of 2004 winners: Keane,” BBC News Online, January 9, 2004, accessed February 15, 2014, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/music/3363889.stm. ↩

- No byline, “Keane still upset with David Cameron and Tories for using their song,” NME, May 17, 2010, accessed February 15, 2014, http://www.nme.com/news/keane/51105. ↩

- Keith Negus, Producing Pop: Culture and Conflict in the Popular Music Industry (London: E. Arnold, 1992), 79. ↩

- Johnson and Cloonan, Dark Side of the Tune, 158. ↩

- Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Grey (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 6. ↩

- Perpetua, “12 Songs Republicans Used Without Permission”. ↩

- Sue Lawley, “Rt Hon David Cameron MP,” 2006. ↩

- Noakes, Splitting Atoms, 2013. ↩

- Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 175. ↩

- Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility,” 25. ↩