More Than A Marimba Bar

Submitted by Alex Smith

The social and cultural relevance of musical instruments extends far beyond their “completed” form for musicians to use in composition and performance. In this post, I explore how musical instruments also have significant value in terms of the living natural materials that comprise them, possessing layered narratives that might be in conflict or competition with their musical application. The inherent significance and alternative values of these materials are often overlooked as global supply chains disconnect musicians from their instruments in relation to the natural resources, people, places, and labor bound up in their construction. My ecocritical work offers several ways for percussionists, (ethno)musicologists, and the music instrument trade to reconsider the complex, multilayered value of rosewood. It also challenges musicians, audiences, and instrument makers to think hard about their position at the intersection of natural life and culture.

***

While musical instruments are objects with socio-cultural meaning and agency (Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things, 1986), this is easy for us as musicians to overlook when our access to them is ongoing and unquestioned. According to Kevin Dawe, “musical instruments are … objects existing at the intersection of material, social and cultural worlds, as socially and culturally constructed, in metaphor and meaning, industry and commerce, and as active in the shaping of social and cultural life (Kevin Dawe, “People, Objects, Meaning,” 2001: 221).” Similarly, Eliot Bates calls for consideration of musical instruments “as neither a subject nor object, but as a source of action” (Eliot Bates, “The Social Life of Musical Instruments,” 2012: 372). In other words, musical instruments both shape and are shaped by the music and culture of their context. Clearly, a professional musician’s ability to perform their trade and “make it” (i.e. pay rent, put food on the table) depends on the existence of and access to musical instruments.

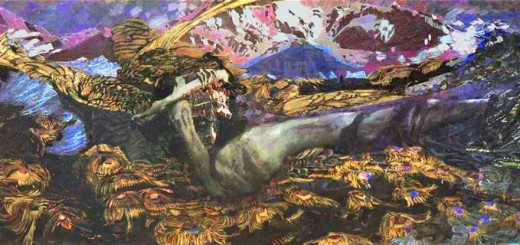

But the materials used to make musical instruments are equally significant. As both a percussionist and an ethnomusicologist, I’ve followed the complex and competing narratives surrounding rosewood—also known by the genus name Dalbergia, many species of which are rare and endangered (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species). This post will draw from two musical contexts for the marimba, including that of the Ghanaian gyil (a West African xylophone) and Western classical music (Figure 1). In juxtaposing rosewood’s musical and non-musical narratives, the complicated and multi-layered reality of musical materials can begin to be uncovered.

Recently I have joined others in arguing that the idea of a “natural resource” is problematic since it implies that nature is a resource to be consumed (Vandana Shiva, Earth Democracy, 2005). The materials used to make musical instruments have their own social and cultural histories and intrinsic value before they are incorporated in the making of musical instruments. I believe these materials, resources, or living things, both in their natural state and as they exist in the form of musical instruments, deserve recognition, respect, and appreciation by those who use them. I recently talked about this topic with my teacher and friend Bernard Woma who is a renowned gyil virtuoso (Figure 2; also look to the end of this post for a video of Bernard playing the gyil). He told me that the Dagara people (a Northwest Ghanaian ethnic group closely associated with the gyil) spiritually value rosewood, or “liga,” as the locals call it.

“In the Dagara tradition you don’t cut fresh rosewood. You wait until the wood dies before you go and cut it to use for gyil. In the event that the wood doesn’t die and you have to cut it … there are rituals that are performed around the rosewood before the tree [can be cut]. We believe that in cutting down rosewood, you are cutting down life; however, we are cutting down the life for a meaningful purpose.” (Figure 3)

A meaningful musical and cultural purpose, that is. Rosewood is regarded as a living entity because of its situation within Dagara culture. Conversely, musicians of the Western academic percussion community are rarely, if ever, involved with the harvesting of rosewood for their instruments due to consumer distancing from where the tree grows. Our view of rosewood is based on a limited relationship with the material as a commoditized marimba bar, obscuring our understanding of the material as a form of life, and thus impacting the ways we value the musical instruments it comprises (Figure 4).

At the same time, the demand for rosewood as a material extends far beyond the music community. The visual aesthetic and physical properties of rosewood make it an ideal material for use in the home, such as for flooring, furniture, charcoal, firewood, and sculpture (Figure 5). While local Ghanaian communities have been using the material in these ways for a long time, the global community has recently begun to demand rosewood for these same applications at large scales. Bernard had this to say about the environmental stress on rosewood as a result of increased demand:

“That’s what the [outsiders] are doing because they know that rosewood is a quality wood for furniture, it is a quality wood for building, it is a quality wood for sculpture, so they come here and they buy it from the government, and they just cut the trees indiscriminately. … So, rosewood [in Ghana] is coming to be endangered.”

Increased demand for gyil by cultural tourists might also be a contributing factor to Ghanaian rosewood’s threatened status. Gyil makers that serve these tourists produce instruments to meet this demand, but some have used material substitutes to rosewood as accessibility diminishes.

The physical agency of rosewood provides another source of value in terms of its anthropomorphic visual and sonic characteristics. For example, rosewood is often described as having a “blood-red” color, and when the wood is smoked over an open fire in the early stages of its material crafting it makes sounds that some compare to human screams. Rosewood can also cause physical allergic reactions in the craftspeople that work with it, having the power to damage human sight, breathing, and skin (Skovsted et al., “Hypersensitivity to Wood Dust,” 2000: 1089-90; Athavale, et al., “Occupational Hand Dermatitis in a Wood Turner due to Rosewood,” 2008: 345-346). As a result, craftspeople must take great care when interacting with this material, and in some cases individuals must avoid it entirely. Collectively this results in a respect, both spiritual and physical, for the relationships between rosewood and the humans that work with it (Figure 6).

The marimba in its many forms—Western, Ghanaian, and beyond—is a complex musical object with a complicated history. Rosewood possesses intrinsic, social, cultural, spiritual, musical, artistic, and domestic value for local and global populations alike. This multi-layered value produces competing and conflicting situations for the people that use rosewood; it can also result in misuse and overuse of the material if demand exceeds availability. But with greater awareness of these complex and often competing narratives, we can achieve sensitivity for the ties that bind materials with their musical, cultural, economic, and natural contexts.

***

Alex Smith is an MA student in Ethnomusicology and teaching assistant at Michigan State University where he also received his MM in Percussion Performance (2014). At MSU, Alex studies percussion with Professor Gwen Dease and Dr. Jon Weber and performs with the MSU Wind Symphony, the MSU Percussion Ensemble, Musique 21, and the MSU Salsa Band; he is also a graduate assistant for the MSU Drumline. In the area of ethnomusicology, Alex is a student of Dr. Michael Largey with research interests involving resource consumption and sustainability in the production of percussion instruments. His research has brought him to Brazil and Ghana.

Patrick Bonczyk, Blog Editor and PhD student at UCLA Musicology, edited this blog post. The EchoBlog is a space where scholars can engage informally with topics of interest in the form of thought pieces, interviews, concert reviews, and more. Please contact Patrick Bonczyk at echojour@humnet.ucla.edu with potential post ideas and submissions.